“Poetic Justice” is described as the second of three films John Singleton plans to make about the South Central neighborhood in Los Angeles.

His first, “Boyz N the Hood,” showed a young black man growing up in an atmosphere of street violence, but encouraged by his father to stand aside from the gangs and shootings and place a higher worth on his life. At the end of the film, the hero’s friend was shot dead.

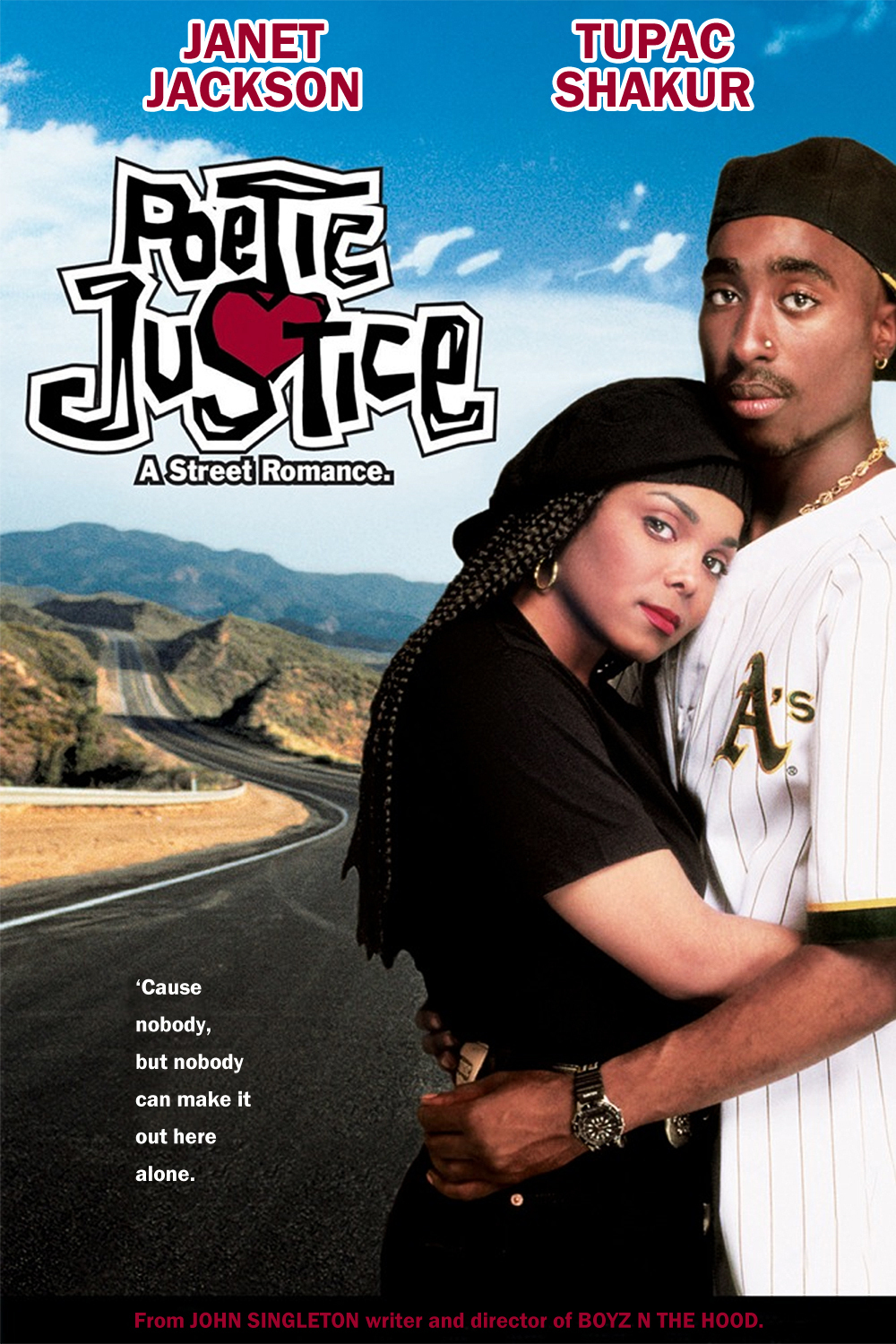

Now comes a film told from the point of view of a young woman in the same neighborhood – Justice, played by Janet Jackson. At the beginning of the film she’s on a date at a drive-in theater with her boyfriend. Words are exchanged at the refreshment stand, egos are wounded, and before long her boyfriend is shot dead. (One of the realities in both films is the desperation of a community where self-respect is so precarious that small insults can become capital offenses.) Justice emerges from mourning determined to go it alone. What’s the use of committing her heart to a man who will simply get himself killed in another stupid incident? She works in a beauty shop, where one day a mailman (Tupac Shakur) comes in and starts making soft talk. She leads him on and then lets him down with a mean trick. But the tables are turned when her friend Simone (Khandi Alexander) invites her to go along on a trip to Oakland. Her boyfriend has a friend who works for the post office and will let them ride along in a mail truck. Of course, the friend is Shakur.

Unlike “Boyz,” which was fairly strongly plotted, “Poetic Justice” unwinds like a road picture from the early 1970s, in which the characters are introduced and then set off on a trip that becomes a journey of discovery. By the end of the film, Justice will have learned to trust and love again, and Shakur will have learned how to listen to a woman. And all of the characters – who in one way or another lack families – will begin to get a feeling for the larger African-American family to which they belong.

The scene where that takes place is one of the best in the film.

The mail truck takes them down back roads until they stumble across the Johnson Family Picnic, a sprawling, populous affair where not all of the cousins even know each other. That makes an ideal opportunity for the four travelers to wander in and get a free meal. But along the way they’re also embraced by one of the cousins, and hear some words of wisdom from another one (the poet, Maya Angelou).

It is Angelou’s poetry we hear on the sound track of the movie; Justice is a poet, and we are told it is hers. She has aspirations and sensitivities, and as played by Jackson she emerges as a sweet, smart woman who is growing up to be a good person.

Her romance with Shakur is touching precisely because it doesn’t take place in a world of innocence and naivete; because they both know the risks of love, their gradual acceptance of each other is convincing.

“Boyz N the Hood” was one of the most powerful and influential films of its time, in 1991. “Poetic Justice” is not its equal, but does not aspire to be; it is a softer, gentler film, more of a romance than a commentary on social conditions. Janet Jackson provides a lovable center for it, and by the time it’s over we can see more clearly how “Boyz” presented only part of the South Central reality.

Yes, things are hard. But they aren’t impossible. Sometimes they’re wonderful. And sometimes you can find someone to share them with.