It is a Sundance subgenre unto itself: A 30ish guy at a crossroads must return to his small hometown from the big city when his mother becomes ill. While there, he deals with his wacky, dysfunctional family, reconnects with an old friend who provides unexpected wisdom and learns some Important Life Lessons, all of which is punctuated by an obsessively chosen soundtrack of emo alternative music.

You’ve seen this movie before. You’ve seen it in the past month, actually: It was called “The Hollars,” directed by and starring John Krasinski. But while that film hit every clichéd note you’d expect, despite its good intentions and great ensemble cast, “Other People” breathes new life into the formulaic, dark comedy about death.

Longtime comedy writer Chris Kelly (“Saturday Night Live,” “Broad City,” “Funny or Die”), making his feature writing and directing debut, shows some strong instincts in upending our expectations. He finds a tricky balance of absurd humor and abiding truth in telling what is clearly a very personal story. And despite some broad moments that feel a bit out of place along the way, he wrings major tears that are wholeheartedly earned by the end. Bring tissues.

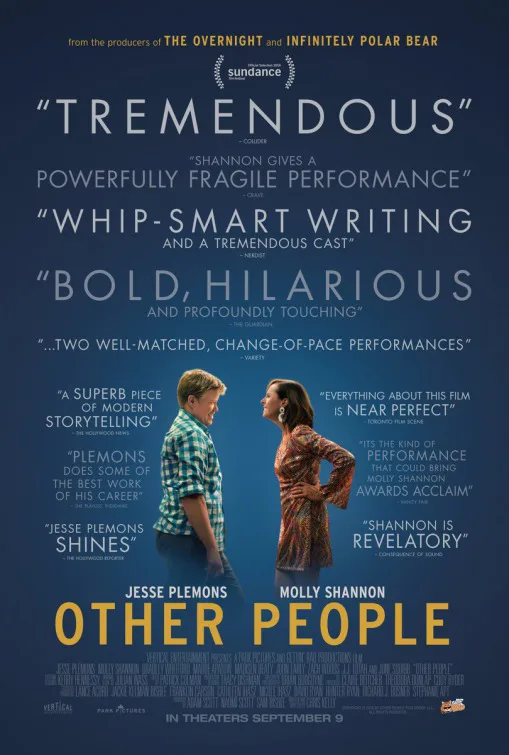

Much of what makes the movie work so well are the moving performances from Molly Shannon and Jesse Plemons in roles that allow them both to stretch in unprecedented dramatic ways. Individually strong as their characters navigate the difficulties of dealing with a rare form of cancer, they have a lovely, sweet and believably lived-in chemistry with each other as mother and son.

Understatement is Kelly’s secret weapon. It’s a risk to dial it down and let the subtlety of surreal humor sneak up on you. While “Other People” begins with a big moment—daringly, THE big moment—then flashes back to a year earlier, the film is more interested in the mundane ways the characters relate to each other and in the minutiae of their lives.

An amiably low-key Plemons stars as David, a comedy writer living in New York who’s struggling personally and professionally after enjoying some quick, early success. He returns to the generic tract house where he grew up in suburban Sacramento to help his ailing mother, Joanne (Shannon), a second-grade teacher who’s about to start chemotherapy. Kelly efficiently establishes who Joanne was at the height of her powers at the family’s annual New Year’s Eve party: fun-loving, no-nonsense, big-hearted. Shannon brings her beautifully to life in all her shadings.

Also living under the same roof is David’s more conservative father (Bradley Whitford), who probably means well but still can’t accept the fact that David is gay a decade after he came out, which leads to some cringe-inducing (and eventually heartbreaking) conversations. He also has two younger sisters (Madisen Beaty and Maude Apatow, branching out from father Judd’s comedies) whom he clearly loves, even though he shares very little with them about his personal life. (Briefly, we also get visits from Paul Dooley and June Squibb as the goofy, clueless grandparents who seem to have wandered in from another movie.)

David actually keeps everything to himself, which puts Plemons in the tough position of making him feel like a fully fleshed-out human being without a lot of opportunities to emote. He’s observant; he sees everything and obviously worries about everything as he’s constantly biting his nails. The few moments he has to get out of the house—and visit Sacramento’s sad gay bar with high school pal Gabe (John Early, a scream)—allow him to complain about his state of flux. There’s the TV pilot he wrote that he hopes gets picked up, but more importantly, there’s the recent breakup with his boyfriend of five years (Zach Woods), which he’s kept a secret from his mother to avoid burdening her further.

A quick trip back to Manhattan leads to an authentically awkward yet intimate sexual encounter between David and his ex—a moment of truth in a film full of them. Another standout is the scene in which Joanne returns to her elementary school for a farewell party before the beginning of the new school year. You can feel the strain in the air as her colleagues fight to keep the conversation light and she tries in vain to regain some semblance of her former self.

She hasn’t got long, though—we know that from the start. That doesn’t make her poignant good-byes any less wrenching. Even if this kind of suffering has happened only to other people and not to you, you’re likely in for an ugly cry. The upside is, you won’t be alone.