Families can go along for years without ever facing the underlying problems in their relationships. But sometimes a tragedy can bring everything out in the open, all of sudden and painfully, just when everyone’s most vulnerable. Robert Redford’s “Ordinary People” begins at a time like that for a family that loses its older son in a boating accident. That leaves three still living at home in a perfectly manicured suburban existence, and the movie is about how they finally have to deal with the ways they really feel about one another.

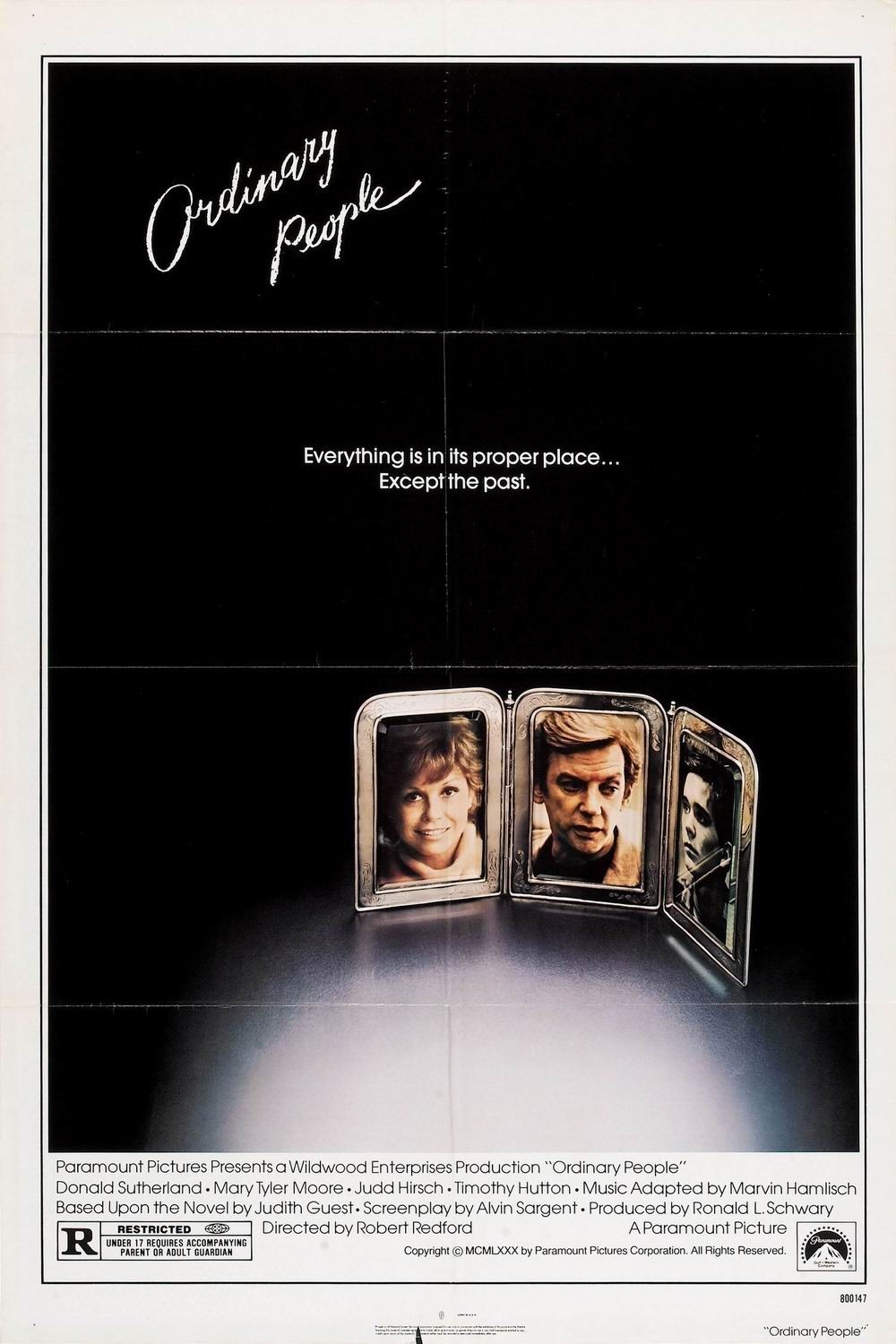

There’s the surviving son, who always lived in his big brother’s shadow, who tried to commit suicide after the accident, who has now just returned from a psychiatric hospital. There’s the father, a successful Chicago attorney who has always taken the love of his family for granted. There’s the wife, an expensively maintained, perfectly groomed, cheerful homemaker whom “everyone loves.” The movie begins just as all of this is falling apart.

The movie’s central problems circle almost fearfully around the complexities of love. The parents and their remaining child all “love” one another, of course. But the father’s love for the son is sincere yet also inarticulate, almost shy. The son’s love for his mother is blocked by his belief that she doesn’t really love him, she only loved the dead brother. And the love between the two parents is one of those permanent facts that both take for granted and neither has ever really tested.

“Ordinary People” begins with this three-way emotional standoff and develops it through the autumn and winter of one year. And what I admire most about the film is that it really does develop its characters and the changes they go through. So many family dramas begin with a “problem” and then examine its social implications in that frustrating semifactual, docudrama format that’s big on TV. “Ordinary People” isn’t a docudrama; it’s the story of these people and their situation, and it shows them doing what’s most difficult to show in fiction, it shows them changing, learning, and growing.

At the center of the change is the surviving son, Conrad, played by a wonderfully natural young actor named Timothy Hutton. He is absolutely tortured as the film begins; his life is ruled by fear, low self-esteem, and the correct perception that he is not loved by his mother. He starts going to a psychiatrist (Judd Hirsch) after school. Things are hard for this kid. He blames himself for his brother’s death. He’s a semi-outcast at school because of his suicide attempt and hospitalization. He does have a few friends, a girl he met at the hospital, and another girl who stands behind him at choir practice and who would, in a normal year, naturally become his girlfriend. But there’s so much turmoil at home.

The turmoil centers around the mother (Mary Tyler Moore, inspired casting for this particular role, in which the character masks her inner sterility behind a facade of cheerful suburban perfection). She does a wonderful job of running her house, which looks like it’s out of the pages of Better Homes and Gardens. She’s active in community affairs, she’s an organizer, she’s an ideal wife and mother, except that at some fundamental level she’s selfish, she can’t really give of herself, and she has, in fact, always loved the dead older son more. The father (Donald Sutherland) is one of those men who wants to do and feel the right things, in his own awkward way. The change he goes through during the movie is one of the saddest ones: Realizing his wife cannot truly care for others, he questions his own love for her for the first time in their marriage.

The sessions of psychiatric therapy are supposed to contain the moments of the film’s most visible insights, I suppose. But even more effective, for me, were the scenes involving the kid and his two teen-age girlfriends. The girl from the hospital (Dinah Manoff) is cheerful, bright, but somehow running from something. The girl from choir practice (Elizabeth McGovern) is straightforward, sympathetic, able to be honest. In trying to figure them out, Conrad gets help in figuring himself out.

Director Redford places all these events in a suburban world that is seen with an understated matter-of-factness. There are no cheap shots against suburban lifestyles or affluence or mannerisms: The problems of the people in this movie aren’t caused by their milieu, but grow out of themselves. And, like it or not, the participants have to deal with them. That’s what sets the film apart from the sophisticated suburban soap opera it could easily have become. Each character in this movie is given the dramatic opportunity to look inside himself, to question his own motives as well as the motives of others, and to try to improve his own ways of dealing with a troubled situation. Two of the characters do learn how to adjust; the third doesn’t. It’s not often we get characters who face those kinds of challenges on the screen, nor directors who seek them out. “Ordinary People” is an intelligent, perceptive, and deeply moving film.