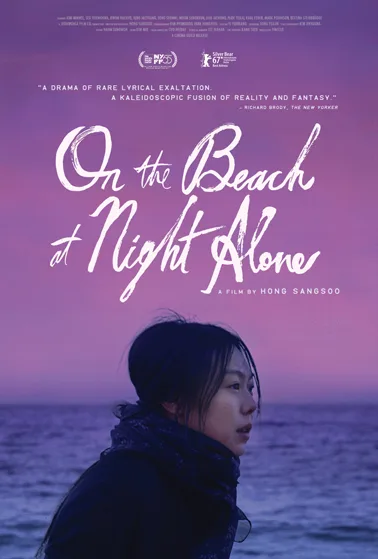

The inert Korean drama “On the Beach At Night Alone” is a prime example of why personal art isn’t necessarily good art. Writer/director Sang-soo Hong (“Right Now, Wrong Then,” “The Day He Arrives“) has taken his real life extra-marital affair with actress/frequent collaborator Min-hee Kim, and created a painful series of talking points that never coheres into a coherent drama. This is especially disappointing since Hong’s films generally rely on his viewers’ ability to recognize patterns within pointedly similar narrative episodes. A typical Hong character performs the same actions over and over again, with minor, but noticeably different results.

Unfortunately, the drama in “On the Beach at Night Alone” isn’t so involving. Scenes of naturalistic small talk are fine enough, but Hong’s drama grinds along whenever characters start to declaim, or make veiled proclamations about marriage and personal freedom. Watching this film feels like running into a depressed, drunk friend who can’t stop himself from yelling about how terrible his life is, and how much hurt he’s causing others. You feel bad for your buddy, but after a certain point, hoo, man, look at the time, gotta run!

“On the Beach at Night Alone” exemplifies all of the worst tendencies of Hong’s films without many of his better qualities. It’s a typical Hong movie in the sense that Hong is concerned with a woman’s vaguely defined sense of independence, and a couple of men’s growing irrelevance. “On the Beach at Night Alone” is also very much like Hong’s other films in that it’s unmistakably told from a man’s point-of-view. The words Hong puts in Kim’s mouth may, in fact, reflect a keen insight into his lover’s feelings. But, outside of that context, Kim’s character, an aimless actress named Young-hee, often rationalizes deeply personal, and painful feelings—on Hong’s behalf.

Young-hee spends the first third of “On the Beach at Night Alone” talking circles around her mild-mannered friend Jeeyoung (Young-hwa Seo). Almost every one of Jeeyoung and Young-hee’s conversations concern the latter woman’s romantic affair with a married man. Young-hee seems resigned to this situation, so she only speaks passionately about this relationship within the abstract: everybody should have the right to independence, and happiness, or variations thereof become a common speechifying theme. This is probably because Hong’s wife has, in real life, refused to grant him a divorce. So now he promotes his affair with Kim as much as possible in a vain ongoing attempt at getting his unhappy spouse to change her mind.

“On the Beach at Night Alone seems to enter a superficially denser thicket of meta-textuality at around the 25-minute mark, when the film’s end credits prematurely roll. Young-hee wakes up in a movie theater. And for a moment, it seems like the suffocatingly myopic nature of Young-hee’s man problems are a little more sensible. This movie is an open-ended plea from Hong to his audience: don’t judge me too harshly, I know I’m hurting my loved ones, but what else can I do? This partly explains the mysterious unnamed stranger in a black over-coat who shadows Young-hee, like the personification of Hong, I mean Young-hee’s guilty conscience, or maybe just her inability to deny the resentment and anger she’s feeling about her current situation. This man in black is the revenge of Hong’s subconscious. Too bad this movie is not about him.

There are many minor flourishes, and points of interest in this film that might existing compel Hong’s fans–and maybe even viewers who have never seen any of his other movies–to see “On the Beach at Night Alone.” But the last hour of this film won’t change their mind one way or the other. This chunk of the film primarily consists of monotonous variations on earlier scenes. Characters talk around, but rarely directly about what’s bothering them. And eventually, after some coffee, cigarettes, and soju, they open up. At this point, you realize that Hong’s characters’ seeming non-chalance and declarative insistence on personal freedom stems from a deeply private place that he only wants to talk about in the abstract. Because Hong’s films are nothing if not a reflection of his personality. For example, their dialogue-intensive style often invites comparisons to the vital work of French New Wave master Eric Rohmer. This is a natural comparison since both filmmakers’ respective bodies of work are defined by discursive dialogue scenes about sex, ethics, and interpersonal responsibility.

But “On the Beach at Night Alone” doesn’t invite comparisons to Rohmer’s films because it has none of the wit, charm, or delicacy of Hong’s superior films. Hong usually excels at an un-fussy, prickly-funny sort of humor that’s often best expressed during grace-less, booze-fueled shouting matches. But even those scenes are dull and shrill in “On the Beach at Night Alone.” Hong has every right to express himself. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that an authentic declaration of his personality is worth watching.