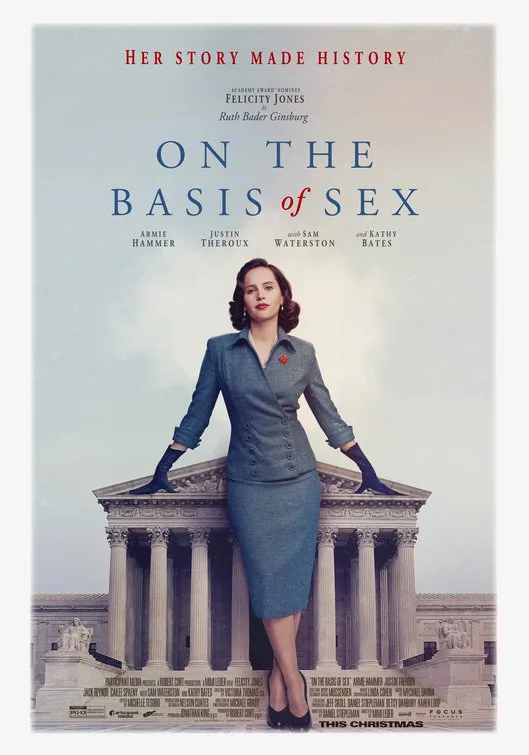

The university’s victory song extols the triumph of the Harvard men, as a sea of dark suits and wingtip shoes walk up the law school’s steps. There is one turquoise dress, one pair of stockings with seams down the back. It was only the sixth year since women were admitted to Harvard Law School and there were just nine women in the class. At a “welcoming” dinner, Dean Erwin Griswold (Sam Waterston) asks each of them to explain why she was taking a space that could have gone to a man. Ruth Bader Ginsburg (Felicity Jones) explains that her husband is in the second-year class and studying the law will help her “be a more patient and understanding wife.”

Was she saying that because she thought that was what he wanted to hear? This movie, written with great affection by Justice Ginsburg’s nephew, Daniel Stiepleman, does not tell us. What it does tell us is that she would be understanding, at least some of the time, but never really patient. Before she was known for her feisty dissents, power work-outs, and “Gins-burns” portrayal on “Saturday Night Live” by Kate McKinnon, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was the pioneer litigator who argued cases that were as important to women’s rights as Brown v. Board of Education was to the rights of racial minorities. And she would have two more run-ins with Dean Griswold, each less patient than the one before.

“RBG,” the well-crafted documentary released earlier this year, capably covers Justice Ginsburg’s life from schoolgirl to the Supreme Court. Wisely, this film focuses on just two key elements: her wonderfully supportive marriage to the late tax attorney, Martin Ginsburg (Armie Hammer) and the one case they argued together, a landmark in outlawing discrimination “on the basis of sex.”

They were still in law school and the parents of a toddler when Martin Ginsburg became ill with cancer. Ruth attended all of his classes as well as her own and helped him to complete his coursework. She met with Dean Griswold to ask if he would allow her the same opportunity he had given male students to finish her last year elsewhere and still get a Harvard degree, making what in my law school days we would call a model argument based on precedent, logic, and the Socratic method. He refused. And so, she graduated from Columbia, first in her class. No law firm would hire her. She put aside her dreams of advocacy and taught law students instead. “You’ll teach the next generation how to fight for change,” the ever-optimistic Martin tells her. This is not one of the times she is patient, telling him, “I wanted to be the one fighting for change!”

And then, he finds a case—a tax case—that gives her that opportunity. The tax law would not allow a deduction for the expenses of an unmarried male caregiver, only a female. She sees that the best way to overturn laws that disadvantage women is to take on one that disadvantages men. It was probably just an oversight; the writers of the tax code failed to consider that an unmarried male might have the care of an elderly parent. But Charles Moritz (Chris Mulkey) did. And the government, under the direction of Dean Griswold, now at the Justice Department, made three very big mistakes. Instead of amending the rule, they decided to fight. They underestimated Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Jones and Hammer make an appealing couple, and they get strong support from the more colorful characters, like Kathy Bates as pioneering feminist attorney Dorothy Kenyon and Justin Theroux as Mel Wulf, legal director of the ACLU (and Justice Ginsburg’s former campmate, as we learn with an adorable musical number). Director Mimi Leder has an eye for telling detail and a sure sense of pacing, especially in the scenes with the Ginsburg’s teen-age daughter Jane (Cailee Spaeny), whose own spirited feminism shows her mother that it is time for the law to catch up with the culture.

Stiepleman’s affection for his aunt and license as an insider are palpable as he gently, perhaps too gently, teases her seriousness of purpose, her discipline, and her legendarily awful cooking. In one telling moment, Martin steals some leftovers from the baby’s high chair tray rather than eat his wife’s tuna-onion casserole. (He later switched over to cooking all the family’s meals, and Hammer shows off some Great British Baking Show-worthy knife skills.) Ginsburg’s determination never falters, but it is moving to witness her growing realization that the world is catching up to her vision, and is ready for her voice.