It’s a mistake to review “Oh! What a Lovely War” as a movie. It isn’t one, but it is an elaborately staged tableau, a dazzling use of the camera to achieve essentially theatrical effects. And judged on that basis, Richard Attenborough has given us a breathtaking evening.

I wasn’t lucky enough to see Joan Littlewood’s original London stage production of “Lovely War,” back in the early 1960s. I was in London at the time, but I was a rash youth and went to see the Windmill girls instead. No matter. It’s a fallacy, I think, to judge a film on the basis of how faithful it is to the book, or to the play, or to anything other than itself.

Like most people, I know World War I at second or third hand, through such sources as Robert Graves’ “Goodbye to All That.” The most dramatic point Graves makes is that the war almost literally exterminated the generation that would have ruled Britain in the 1930s and 1940s. Something like 90 per cent of the field officers were killed on some fronts. Joseph Losey’s film “King and Country” shows us Tom Courtenay as the lone survivor of his original unit; every other man had been killed, and many of their replacements had died as well. This was apparently fairly common.

And so this tragic event sank into the bones of the British memory. America, which came into the war rather late and sustained much lighter casualties, could afford the luxury of a “lost generation” in the 1920s. England literally lost her generation; it was dead and buried, and we seem to see it beneath the countless crosses stretching out behind John Mills in the last, stunning graveyard shot in “Oh! What a Lovely War.”

And yet war films and books have usually not recorded this loss, or the enormity of the stupidity which caused it. Those which have (like “King and Country”) have done it in microcosm; we care for the Courtenay character, but we do not reflect on the total war. “Oh! What a Lovely War” does recreate this time, in a bitter mixture of history, satire, detail, panorama and music.

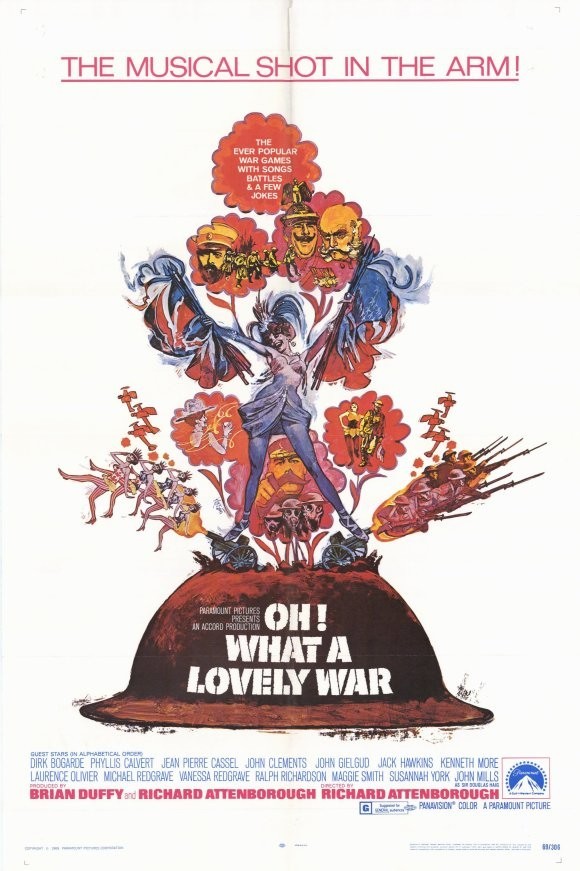

Especially music. There is something paradoxical in the thought of singing about a war, and yet cheap popular songs often capture the spirit of a time better than any collection of speeches and histories. Miss Littlewood, and Attenborough after her, present the war as a British music hall review; there’s a lot of smiling up front, but backstage you can see the greasepaint and smell the sweat, and the smiles become desperate, and there begins to be blood.

This sense is captured most tellingly in Maggie Smith’s scene. She plays a robust, patriotic broad who lures the young men from the audience to the stage with promises of love and implications of heroic death. But death is reserved for the young, not for the old, and John Mills (as Sir Douglas Haig) stays far behind the lines, studying the front from an observation tower. Meanwhile, politicians, kings and rulers play stupid games of diplomacy and etiquette, and “acceptable losses” are counted in the hundreds of thousands. But always everyone whistles a happy tune….

The film is populated with a gallery of British stars. All the knights and ladies seem to be there, and everyone else, too: Olivier, Gielgud, Richardson, at least three Redgraves (and Vanessa looking especially spirited), and the rest. But the important thing is that Attenborough doesn’t use them as a freak show, as Michael Todd did with his cameos in “Around The World In 80 Days,” or as happens in the upcoming “Battle of Britain.” The abilities of these great actors are employed, as well as their names and faces, and together they recreate a horrible war. And the deepest impact of the film comes from the realization that there have been wars even more horrible since this one.