Following a successful performance on the river in San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba, actor Alex (Alexander Diego) states that the work is site-specific and could not be replicated in a different location. Edith (Edith Ibarra), his partner and a talented puppeteer, suggests that their act could perhaps occur in the Amazon, to which Alex replies that people in the Amazon should create their own artistic expression. He is, however, not opposed to the idea of filming it, as it would preserve its integrity, even if it would change for the camera.

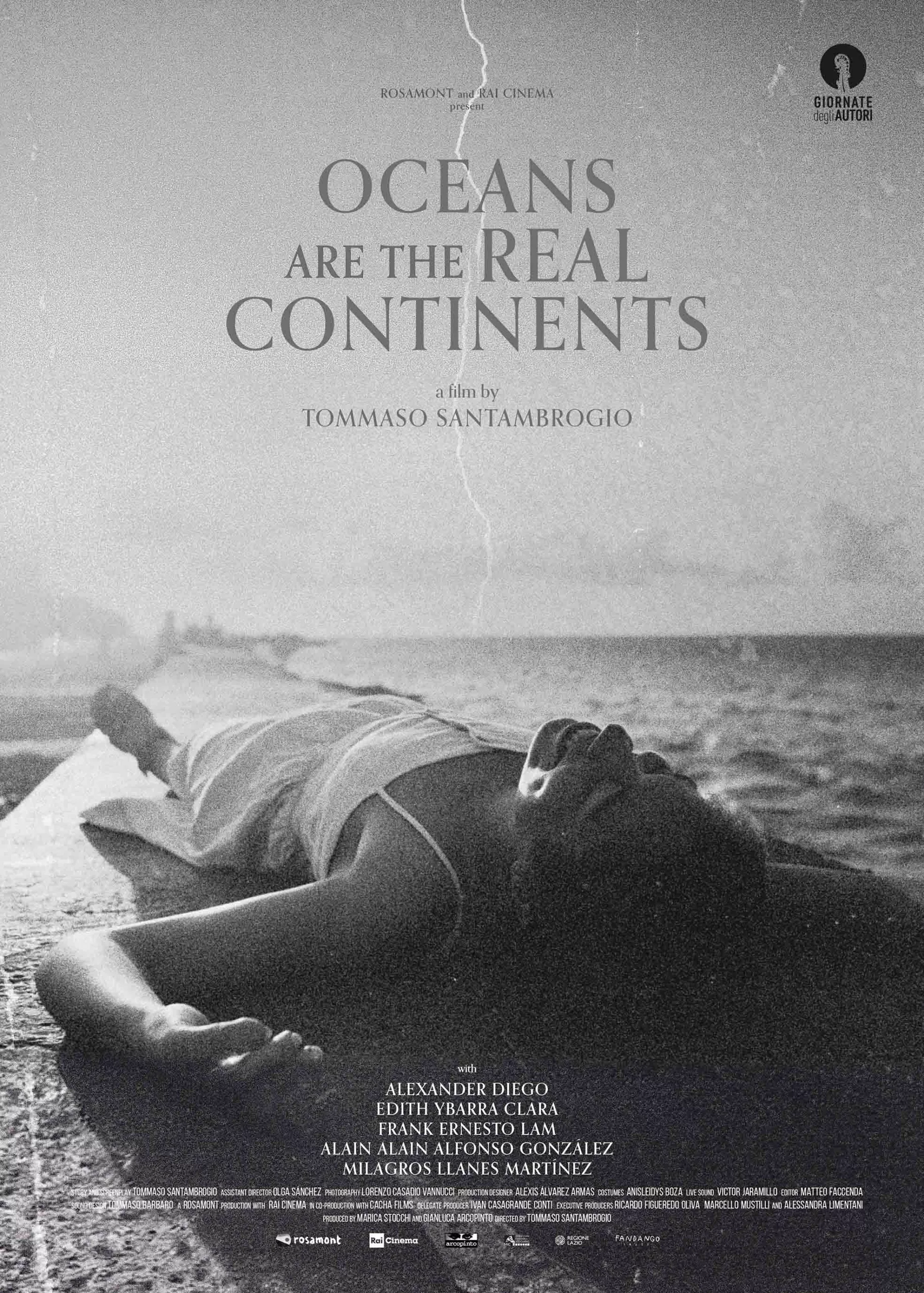

Such debate about the intrinsic ties a work of art has to its context is essential to “Oceans Are the Real Continents,” the exquisitely realized neorealist first feature by Italian director Tommaso Santambrogio. Though not originally from the island, the filmmaker has lived in Cuba for extended periods, and, if this film is any indicator, his relationship with the country and its people goes beyond the trivial. Santambrogio’s narrative triptych could only exist in this location, but he’s filmed it so it can travel the world.

Each of his characters is either burdened with the prospect of leaving Cuba or the distress of being the one who stays behind. Edith’s puppet show presents her with an opportunity to travel to Italy. She has no intention of returning, a reality that perturbs Alex. Baseball-obsessed best pals Fran (Frank Ernesto Lam) and Alain (Alain Alain Alfonso González) dream of growing up and playing for the Yankees and living in side-by-side mansions. The thought of that innocent utopia carries them along. But Frank’s father is migrating to the U.S., and eventually he will too, which could mean never seeing his buddy again. The chance of a share future, weather in the major leagues or not, will disappear.

And then there’s Milagros (Milagros Llanes Martinez), who seems trapped in the past, lost in the many letters that her beloved Miguel wrote to her while on the frontlines in Angola during the 1980s. Though she doesn’t speak, her daily life moves with an unstoppable diligence, as if she were fulfilling a divine duty. Those letters are her only lifeboat in a sea of sorrow. On the radio she hears of modern problems but appears immune to them. These three parallel stories, which only intercept once, illustrate how the past, present, and future of Cuba coexists in the same timeline because nothing much has changed in decades here. Santambrogio’s extraordinary cast of non-professional actors convey a lived-in, personal, and impossible to fake connection to the pleasures, struggles and intricacies of life in Cuba.

Through a montage of photos that he took of her, Alex wonders if Edith will remember him, as she becomes someone new away from the places and the people that shape her. What kind of puppet show will she create influenced by Paris or Rome? And if the bodies of water are in fact more prominent than land masses, as the title suggest, does that mean they will remain close to each since there will be mostly free-flowing water between them? There’s comfort in believing the other person is only on the shore across the liquid barrier.

Filmed with marvelous attention to subtle contrasts possible in its monochromatic palette, the frames brim with a built-in timelessness. These are expertly conceived photographs in motion, which look as if they could come from any time in over the last century. Thoughtful cinematographer Lorenzo Casadio’s delicately illuminated and composed shots illustrate life as it is but seen through the filter of cinema, which adds an aesthetic melancholia to these quotidian, meditative portraits amid buildings weathered by humidity, by the sun, by neglect, and by the cruel passage time. In turn, the elements make themselves present in the form of sound. Alex and Edith sit on their bed in silence while the sounds of a storm envelop them as if happening indoors. And when Alain asks Frank to close his eyes and imagine the beach, the breeze blows in his ears.

Everything stays seemingly unchanged. At one point, Alex and a childhood friend reminisce about their unfilled ambitions of becoming a baseball player and a cosmonaut respectively, not unlike Frank and Alain. Leaving is the best chance Frank has at something greater. But the boy doesn’t want a new life somewhere else. Is that so bad? Fittingly, Santambrogio explicitly invokes Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s 1958 novel “The Leopard,” a text encapsulated in the line, “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.”

In one of the film’s most mesmerizing sequences, excerpts from of Edith’s puppet show occupy the screen. Two faceless marionettes perform the story of a musician father who leaves his painter son behind to play the violin abroad. Separated, it’s only through letters and memories that they remain present for each other. The creation of this heartfelt vignettes on strings, and the notion that Edith will put in for people who live on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, confirms art is a message capable of swimming across latitudes.