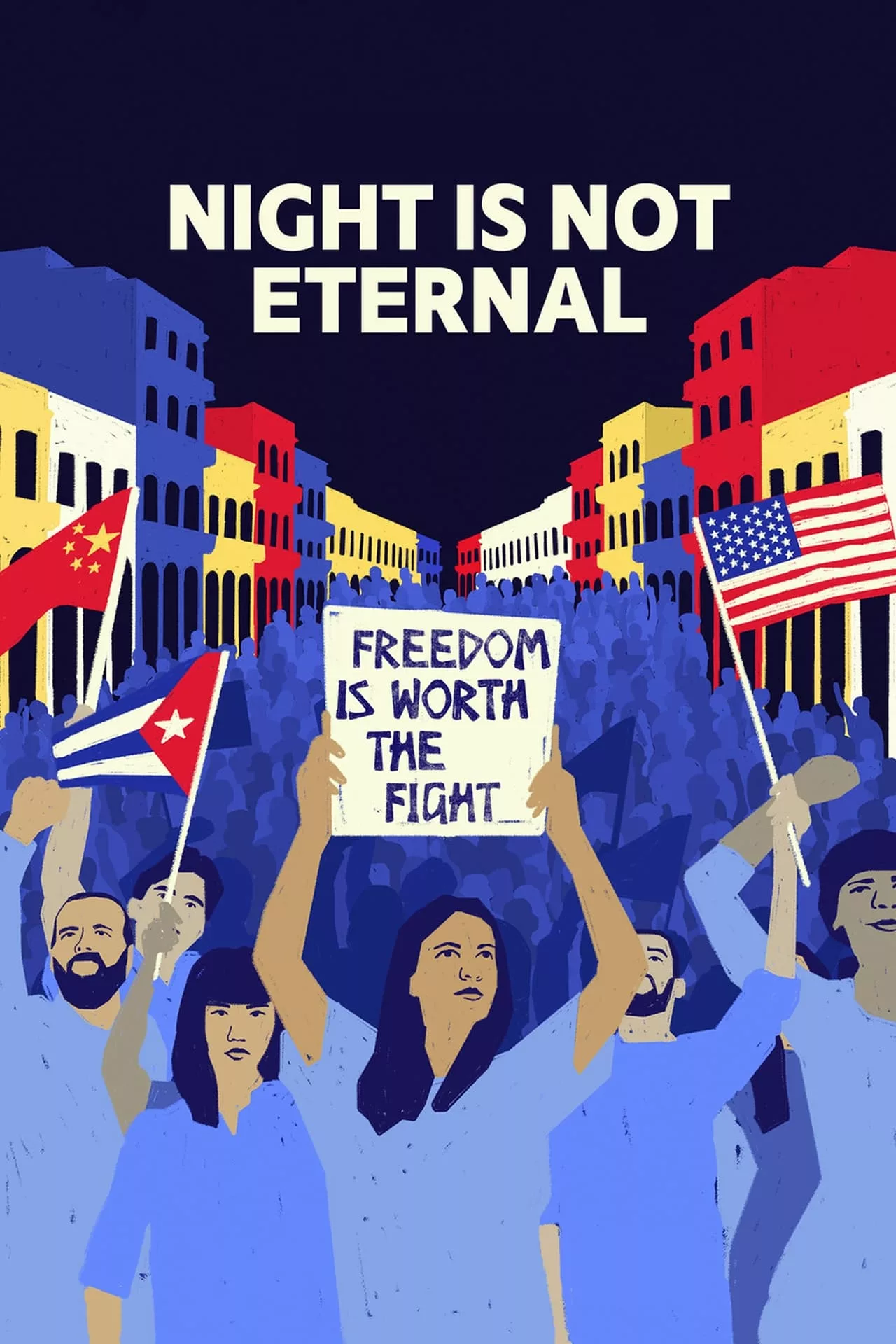

Over the past decade, documentarian Nanfu Wang has crafted a filmography that seeks to explore the systems at play in not just authoritarian countries but those where fascism slowly creeps up like vines. In her latest documentary, the dense and fiercely political “Night Is Not Eternal,” she traces the similarities—and pointed differences—between her cinematic activism after leaving China and that of Cuban activist Rosa María Payá Acevedo. The result is a striking look at the sacrifices and concessions people make in the fight for freedom and how propaganda can make it seem impossible to win.

The first half of the documentary establishes how Wang and Acevedo met after a screening of Wang’s first film, “Hooligan Sparrow,” and found kindred spirits in each other. The daughter of renowned activist Oswaldo Payá, Acevedo and her family had to flee to Miami after his murder in 2012. After their meeting a few years later, Wang spent years documenting Acevedo’s activism on the ground in Cuba. Following Fidel Castro’s death in 2016, the country seemed on the brink of change—that is, until the regime’s military cracked down even harder on activists and artists pushing for democratic reform. This section almost plays like a paranoid thriller, as Acevedo, her fellow activists, and even Wang are repeatedly followed by shady figures in suspicious cars. Eventually, when direct actions on the ground become too dangerous, Acevedo turns more towards policy work and meets with every world leader she can.

As the young woman Nanfu first met slowly transforms into the face of a movement, their parallel journeys split. The birth of Wang’s first child in 2017, during the first Trump presidency, inspired her doc “One Child Nation” and also changed her relationship with America. “I left China and came to the U.S. because of its promise of democracy and freedom,” she shares over narration, but that what she was seeing at this time was a country that was “less free and becoming hostile to people like my son.” As the pandemic raged, Wang made “In the Same Breath,” her sobering look at how both the Chinese and American governments mishandled the outbreak of COVID-19. At this same time, she witnessed Acevedo standing behind Trump at a rally in Florida. Then, at a conservative conference called “Victims of Communism,” Wang later gives Acevedo space to discuss her appearances at these events. Still, her answers further show what happens when activism meets the murky world of politics and diplomacy.

Wang then considers the differences between Acevedo and herself. From the filmmaker’s perspective growing up in China, she would not blame the ideology of communism or socialism on that country’s vast inequality. After leaving the country as an adult, she came to realize it is a country that claims to be following the tenets of socialism, but actually more closely resembles a capitalist country, complete with hoarding of wealth by a select few, the exploitation of workers, and a goal of maximizing profits over people. Wang deftly shows how China and the U.S. have more in common than either country would be willing to admit—and how both use propaganda to convince their populace that they’re something they are not.

The final third of the film compares the July 2021 protests in Cuba and their aftermath to the Tiananmen Square protests from 1989 in China. Both were youth-led movements of unity where the possibility of democracy in both countries seemed palpable, and both were squashed by similarly brutal and oppressive tactics from their respective governments. In Cuba, cellphone footage of the marchers was suppressed by limiting access to the internet. In China, the 1989 protests were not covered by the state-run news. Wang, who was three when they happened, did not learn about them until after she had immigrated to the United States. Yet, both sparked fires that are still burning today.

As the film wraps up, Wang says, “I didn’t feel any closer to understanding where change will come from than when I started.” And neither will the viewer, although the film is so full of information and Wang’s thought-provoking connections that by the time it’s over, you might feel like you’ve taken a semester-long college course. Despite all the footage of government oppression—in Cuba, in China, and even here in the United States—”Night Is Not Eternal” is ultimately a hopeful film. Real change, Wang reminds us, doesn’t have a beginning or an end but rather grows slowly “with its roots tangled in history.” In the ongoing fight for an equitable future, sometimes knowledge and optimism are the greatest tools one can possess.