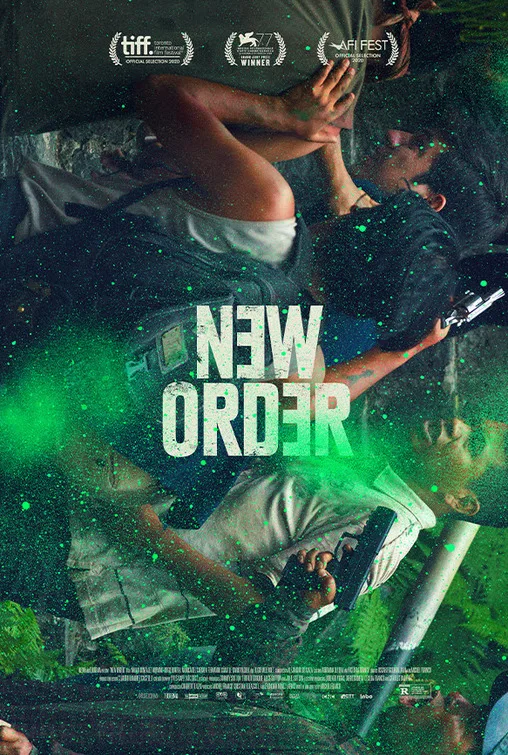

A near-future dystopia that navigates a fractured society hours away from collapse, Michel Franco’s “New Order” is a relentless and blood-soaked study of social injustice, gripping to watch despite its graphic and escalating brutality. Sadly, it’s also one that only vaguely engages with the need for prosperity for all. That imprecision is so intense that often times you wonder what exactly it is that Franco’s film mutters about the universal topic of class warfare and whether the writer/director is actually saying what he intends to say about this ever urgent subject matter, amid some on-the-nose symbolism, and various exploitative images of piling corpses.

Not that films or filmmakers have a duty to prescribe a clear-cut and perfect ethical code to the viewers and package it with a pretty bow—there is value in leaving the final judgment to the educated eye of the beholder. The problem with “New Order” isn’t so much its decisive sense of objectivity or amorality, but rather, its stubbornness to pursue the perspective of the oppressor, while carelessly implying, “there are good and bad people on both sides.” It is entirely likely that “New Order” actually wishes to align itself with something like Bong Joon Ho’s “Parasite,” a masterwork that dissects the bloodsucking evil that is societal economic disparity with ingenious thematic and stylistic assurance. But perhaps unintentionally, it treads closer to, of all things, Christopher Nolan’s “The Dark Knight Rises.” While Nolan’s Batman chapter that sees the uprising of the financially oppressed deserves all the credit for noticing something impending in the air (the film was conceived pre-Occupy Wall Street, but released during it), it left a confounding message behind by looking for its heroes in the wrong place, among the wealthier ranks.

This is more or less what Franco does with “New Order” over approximately 90 nail-biting minutes that tell a fictional tale of a coup d’état somewhere in Mexico. It all starts rather abstractly with the shot of a suggestive painting and a naked body splashed with green paint that in unison scream wealth and money. The sequence that follows confirms the insinuation. We are on the grounds of a handsome, upper-class estate of an obviously well-off family. They are celebrating the marriage of their daughter Marianne (Naian González Norvind) to the successful Alan (Darío Yazbek Bernal) with a classy affair outpouring with stylishly attired guests.

When he shows up uninvited at the house, Rolando (Eligio Meléndez), a former, trusted long-time employee of the family, looks nothing like the flashy guests. He humbly speaks with the matriarch Rebeca (Lisa Owen) first, who is already distressed because of some inexplicable green water coming out of the bathroom sink and doesn’t seem to have that much time for Rolando’s life-and-death predicament. Still, the old man swallows his pride and asks for a large sum of money for his wife’s heart surgery. He explains that it is taking place at a private and expensive hospital after he had to transfer her due to violent protests all around the city. (Are we supposed to blame the protestors here? It’s unclear.) Rebeca brushes him off with only a fraction of what he needs, and so does Marianne’s brother Daniel (Diego Boneta). When Marianne, who deeply respects Rolando, learns about the situation, she decides to give him her monetary wedding gifts, but gets told off both by her father Ivan (Roberto Medina) who has connections to the military and husband-to-be. “It’s your wedding day, just enjoy,” everyone advises. Except, the celebrations predictably come to a halt once the protests in the streets seep into the property in the most violent way, while Marianne heads out with loyal housekeeper Marta’s (Mónica del Carmen) son Christian (Fernando Cuautle) to find Rolando and pay for the medical emergency.

The city-wide situation escalates, nearly erasing the class divide once the military authoritarianism and governmental corruption seize their opportunity. What follows—instances of mass murder, sexual assault, utter cruelty and a mounting body count that Franco seems dangerously pleased to put on display—is hard to watch, even though it is absorbing, impressively sure-handed filmmaking. Throughout the movie’s taut running time, Franco shows, above all else, what a master craftsman he is, with his camera cleanly and confidently charting a time of social and political unrest with startling scale and scope. But somewhere along the way, especially when he decides to make the rich Marianne with the heart of gold the main interest of the story (while leaving most people on the opposite side of the social order anonymous), he loses his handle on the compass. Or maybe he never had that much of a direction to speak of.

Now playing in theaters.