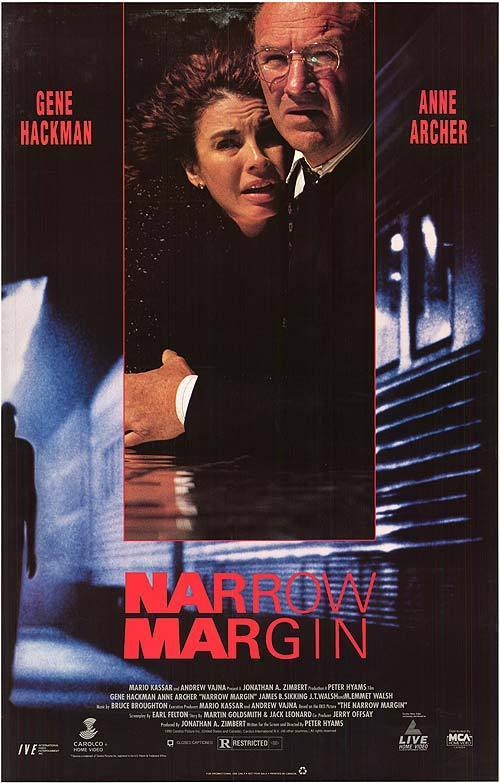

“Narrow Margin” is a clumsy version of the Idiot Plot, dressed up as a high-gloss chase thriller. The Idiot Plot, of course, is any plot that would be resolved in five minutes if everyone in the story were not an idiot. And rarely has there been a film in which more idiots make more mistakes than in this one.

The story involves Anne Archer as a woman who goes out on a blind date and accidentally witnesses the man’s murder by a mob killer, while the killer’s boss – a crime kingpin – looks on. Archer is terrified that she will be the next victim and immediately escapes to her secluded cabin in the Rockies, telling nobody – except, of course, for her roommate, who tells the police, who follow her there in a helicopter, and who are followed by another helicopter they fail to notice.

Gene Hackman plays the lawman on her trail. When the second helicopter starts spraying the cabin with machinegun bullets, he leads her out the back window and into a waiting truck, so they can speed down the road while providing a target for more bullets. He eventually drives under the protection of tall trees, but soon he’s out in the open again, as this chase sets a pattern for the movie by dragging on much too long.

Eventually the chase leads to a train station, and wouldn’t you know that a train is just pulling in. It sits at this whistle-stop in the middle of the woods long enough for Hackman and Archer to buy tickets and talk an old couple out of their private compartment on the grounds that Archer is about to go into labor. Nobody asks (a) why a woman about to give birth would take a train ride instead of going to the hospital, or, more pointedly, (b) why she doesn’t look remotely pregnant (to fool the oldsters, she sticks her hands in the pockets of her sweater).

Hackman and Archer are followed onto the train by two or more killers, who have parked their helicopter nearby, I guess. What follows is an endless series of scenes in which killers and quarry follow each other up and down train corridors. The killers invariably make a habit of entering one end of a car and not seeing Hackman until he can duck out of sight at the other end. Then there is time for long, soul-searching talks at night, because, as Hackman says, “They won’t act until morning because they don’t have to.” Meanwhile, the train has turned into an express to Vancouver, shortly after stopping to pick up those folks in the woods.

As a connoisseur, I appreciated a scene in which Hackman and Archer are safely hidden in a compartment but he leaves to go to the diner for coffee and is found by the killers. And another scene in which the bad guys try to bargain with him. And another scene in which it is obvious to everyone but Hackman that a woman is not as innocent as she seems. And the scene in which Hackman and Archer climb onto the top of a moving train, where the lawman, pushing 60, runs up and down and engages a bad guy in hand-to-hand combat. And a scene in which . . .

But never mind. I have more. How about the fact that there’s not even a scene in which Hackman confronts the man who betrayed him? (It’s handled over the telephone.) Or the way Hackman tells his backup to “meet me at the border,” without saying where at the border? My favorite moment is when Hackman uses the oldest trick in Western lore to mislead the guys chasing him: He throws a pebble into the woods, and when they go that way, he goes this way. I thought Hopalong Cassidy had retired that particular ploy, but I guess not.

Film footnote. One of the newest cliches in the movies is the use of a black actor to play the obstructionist superior officer in a police drama. How many times have we seen the hero called on the carpet in the office of his superior, a black man who orders him to stop hot-dogging around? This character is invariably wrong-headed and obtuse. “Narrow Margin” introduces a character like that, who then disappears except for mention in a phone call. In the bad old days, black actors were often cast in menial roles. Now they are cast as token superiors, but the stereotyping is just as relentless. What’s the worse role, pushing a broom, or being kicked upstairs? Why not let some of these actors into the mainstream of the plot?