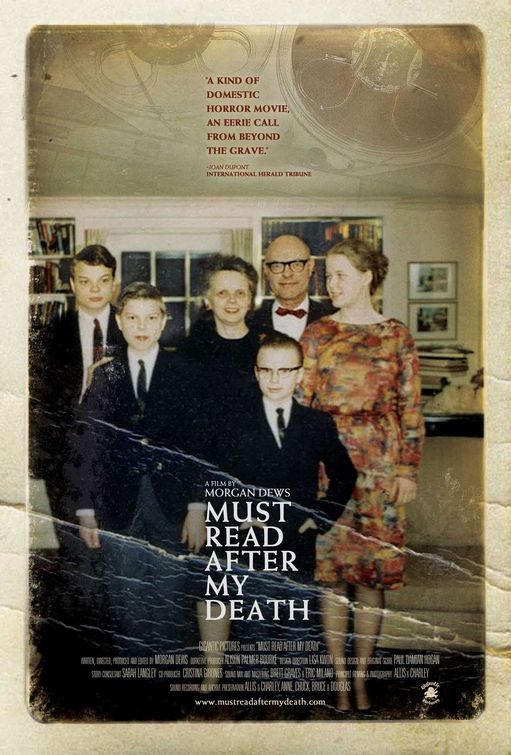

Here is a cry from the grave. A woman who died some eight years ago at the age of 89 left behind about 50 hours of audiotapes, 200 home movies and 300 pages of documents, a record that all ended, 30 years before that, on the death of her husband. The cache was labeled, in bold marker on a manila envelope, “Must Read After My Death.” What an anguished story it tells, of a marriage from hell.

The woman was named Allis. Her grandson, Morgan Dews, has created this film from her archives, and understandably represses her family name. She met her husband, Charley, when they were both married to others. What she wanted was a nice little house with a white picket fence, where she would bear his children, whether or not they were married, because she knew they would have beautiful children together. They were married, and until death did not part.

It was an “open marriage.” Charley was away much of the year in business, often to Australia. They decided to exchange Dictaphone recordings, and later tape recordings, and Allis saved hours of taped telephone messages. Charley is forthright about his adventures with “interesting women” he has met in Australia, “good dancers” and obviously good at more than that, but “the international operators listen in.” Allis tells only of one weekend affair. She says she thinks she “helped” the man rebuild his self-confidence.

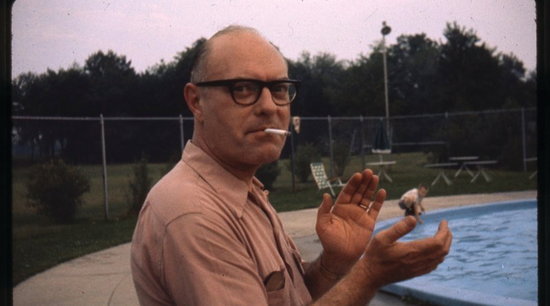

Charley is such a perfect bastard. His dry voice objectively slices through everything. He speaks of love and travel arrangements in the same tone. When he’s home, there is always fighting. Always. Not about sex; he sees the real problems in their marriage as housekeeping and finances. Allis says she was meant to be a good mother but was never a housekeeper. She speaks four languages, went to college, was married first to a European, did some kind of unspecified singing. We hear not a word about Charley’s first marriage.

Charley and Allis have three sons and a daughter. Charley is relentless with them about their “chores.” He’s an alcoholic, and it seems to make him a perfectionist. He’s tall, balding, handsome in that Harry Smith way. Allis is small, tidy, worried. There are tapes of screaming rages involving Charley and his sons; their daughter, Morgan’s mother, not much heard, leaves home at 16, following the advice in Philip Larkin’s famous poem about destructive families “This Be the Verse:”

Get out as early as you can.

The first line of that poem certainly describes the marriage of Charley and Allis. All four children are angry, miserable, neurotic in various ways. The family falls into the clutches of a psychiatrist named Lenn, who wrongly sends one son to a mental institution, diagnoses Charley as “the worst inferiority complex I’ve ever seen” and strews misery and anguish as freely as his advice. What we learn of the children later in life is that three of them, anyway, grew up into apparently happily married adults with children.

It was the family itself that was toxic. They needed to get out. Charley is hated by the children, and Allis thinks of herself as not meant for such a life. She and Charley never have a real talk about “open marriage,” but it certainly suits good-time Charley, a man without a single moment of introspection in this film.

Home movies and now the ubiquitous videotape mean that everyday lives are now recorded with a detail not dreamed of earlier. We will never hear all Allis’ recordings and see all her images, but this distillation by Morgan Dews might have been what she had in mind when she stored away those records of pain. They act as her justification of her life, her explanation of the misery of her children. I watched this film horrified and fascinated. There is such raw pain here. Allis might have read or seen “Revolutionary Road” and by comparison envied that marriage.

There are things you will see here that will lead you to some conclusions. I will leave you to them. All I can say is that I believe the daughter’s guess at the end is correct. We learn that after Charley died, Allis moved to her own small cottage in Vermont and “continued her volunteer work.” She lived another 30 years. She never mentioned Charley again.

The film opens today in New York and Los Angeles, and is available online at www.giganticdigital.com.