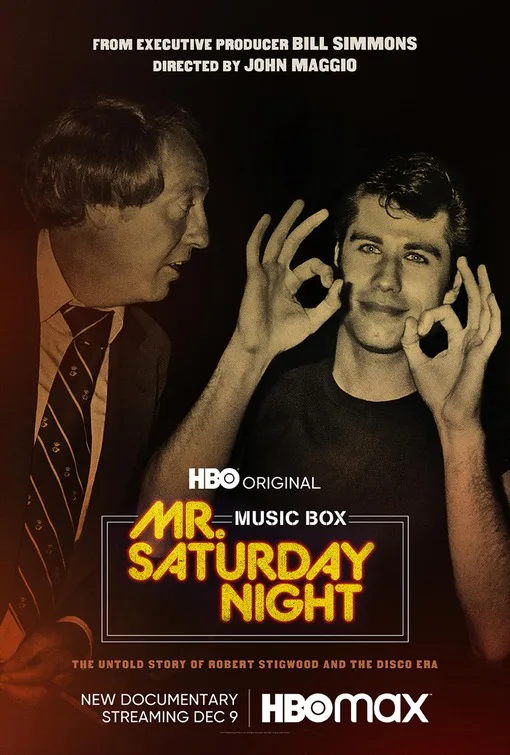

Confusingly for some, perhaps most confusingly for Billy Crystal fans, this movie has the same title as Crystal’s 1992 Anatomy of An Old-School Standup movie, an arguably interesting self-laceration under the guise of a laceration of an alter-ego. This movie, a documentary directed by John Maggio, part of HBO’s Bill-Simmons-produced “Music Box” series, is an almost entirely laudatory work, celebrating a few of the greatest coups in the career of music manager and film producer Robert Stigwood.

The “Saturday Night” of the title is “Saturday Night Fever,” an early foray into the movie world for Stigwood, who prior to the 1977 release had been running things for the likes of Cream and the Bee Gees. And that was truly the only way the man could be characterized as a “Saturday Night” kind of guy. The Australian born Stigwood was, at the first peak of his music career success, was described by the BBC as “diffident” and “awkward.” Early in his career he attached himself to Brian Epstein, and by the mid-60s the Beatles brainiac was ready to hand over the reins to his entire music kingdom to Stigwood. But the Beatles themselves balked, so Stigwood ran off with the Bee Gees and Eric Clapton (Cream having imploded) and set up shop in New York.

Maggio’s’ movie describes the unprecedented deal Stigwood made with rising TV star John Travolta, locking him up for three movies. The manager then had to concoct the movie. An assistant brought a magazine feature by rock journo Nik Cohn to his attention, about disco culture in farthest Bay Ridge, Brooklyn (which Stigwood characterizes as “a ghetto” in an archival interview).

Stigwood, intrigued by the R&B directions in which the Bee Gees were then pushing their music, compelled them to write for the soundtrack before a foot of film was shot. Maggio’s movie, not content to deal with Stigwood’s actual achievements, tends to make big deals out of very little. One interviewee speaks as if it was unheard of to make major motion pictures out of magazine articles, which is a myth so wafer-thin you can crack it with a thirty-second Google search.

But the movie does offer some neat anecdotal goodies. The first director for “Fever,” John G. Avildsen, decided he didn’t want the Bee Gees songs in his picture. The account of his near-instant firing is pretty funny. It’s gratifying, too, that in wresting artistic control of the picture from Paramount, Stigwood became a thorn in the side of Barry Diller and Michael Eisner, two of the most odious figures in Hollywood’s executive class.

“Robert had an extraordinary instinct,” says Nik Cohn in an archival interview. As it happened, in movies he only had it twice. With “Fever” and its follow-up “Grease.” But as it also happens, twice was enough: those pictures yielded him and the Bee Gees what they call untold wealth. There’s a lot of overlap here with last year’s Bee Gees documentary “How Can You Mend A Broken Heart” and probably many other accounts of ‘70s music. Maggio’s treatment of the infantile, homophobic and racist anti-disco movement is brief but pungent—he unearths a repulsive TV clip of rock belter Meat Loaf quoting a homophobic Ted Nugent comment, approvingly.

Like “How Can You Mend A Broken Heart,” this movie also participates in blatant “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” erasure. Not the album, which Stigwood had nothing to do with. No, the movie musical, a notorious bomb, starring the Bee Gees and Peter Frampton, produced by Stigwood. Perhaps this Unique Object was Stigwood’s revenge on the Beatles for them not allowing him to take over their management. Who can say? Not this movie.

The movie also, ultimately, doesn’t illuminate Stigwood himself to any great degree. There’s some discussion of what used to euphemistically be termed his “confirmed bachelor” status—like his mentor Epstein, Stigwood was gay—but no real exploration of how his exposure to the disco subculture affected his life. It’s also frustrating that there are no new interviews with Travolta—this account makes it clear that he owes his career to Stigwood. The movie gives pretty good showbiz lore but not much depth.

On HBO this evening.