There comes a moment in “Music Box” when several important photographs pop up, one after another, from the bowels of a music box – as if they were being ejected by a copying machine. It is intended as a dramatic moment, but it is all too neat, the clockwork machinery operating right on time for the requirements of the plot, and the entire movie is like that. It is put together out of pieces taken off the shelf, and although it is about suffering, trust and family love, it has no heart.

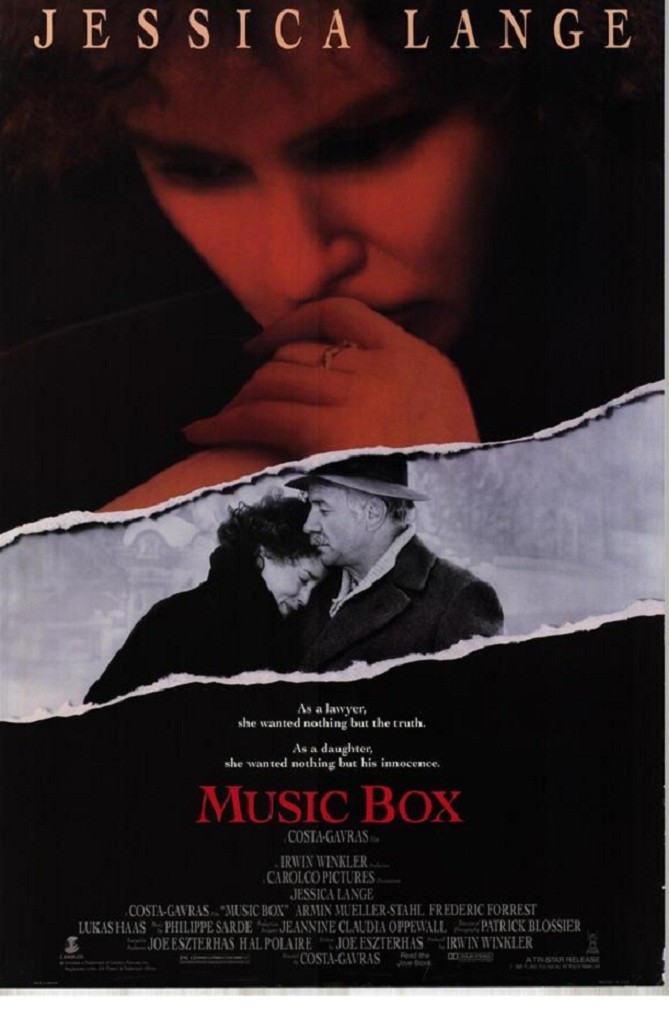

The movie stars Jessica Lange as a Chicago attorney whose father, an immigrant from Hungary, has led a blameless life for many years. He is loved by all who know him. Then investigators appear to accuse him of being a Nazi war criminal. They want to put him on trial for his crimes and deport him. The daughter, of course, is convinced of her father’s innocence. It is all a mistake, some kind of insane bureaucratic nightmare, and she will defend him in court and prove that they have the wrong man.

Consider for a moment the possibilities in this plot. Is it possible that the movie could end with the old man found innocent? No, it is not. There is no market for a movie about Nazi-hunters bringing false charges against the innocent. So the man must be guilty. Either that, or the plot must “really” be about something else – with the issue of guilt only a smoke screen. What I particularly disliked about “Music Box” is that it takes the easy way out. It is not about guilt or innocence; it is a courtroom thriller, with all of the usual automatic devices like last-minute evidence and surprise witnesses.

This is the second movie in two years by the team of director Costa-Gavras, writer Joe Eszterhas and producer Irwin Winkler. The previous one was “Betrayed,” the 1988 thriller starring Debra Winger as an FBI undercover agent who falls in love with a seemingly decent young man (Tom Berenger) and then discovers he belongs to a right-wing neo-Nazi group. At first she believes he cannot be guilty – he is too nice a man to believe those things. Then her life is endangered as she discovers that nice guys can deceive you.

“Betrayed” and “Music Box” are in many ways the same story: A decent liberal woman loves and trusts a man who may be a Nazi. In both cases, the Naziism is used only as a plot device, as a convenient way to make a man into a monster without having to spend much time convincing us of it. Neither movie is really about Naziism, but about the plot requirements of a thriller.

But both movies use their moral righteousness in an attempt to seem more serious than they really are. Think back to “Jagged Edge,” the screenplay Eszterhas wrote just before “Betrayed,” and you will see the plot device more clearly: A young woman (Glenn Close) loves a man (Jeff Bridges), who may be a killer, and may kill her. It is just the same idea, spun out in three different ways in three screenplays in a row.

What is most offensive about “Music Box” is that it makes no particular attempt to understand the personality of the old man, who may have been a Nazi. As played, quite effectively, by Armin Mueller-Stahl, he is a decent, God-fearing man, respected in the community and loved by his family. He protests that communists have conspired to frame him because of his anti-communist past. The plot provides some reasons to believe this, and other reasons not to. The final revelations all come out of the courtroom and not out of the old man’s soul, because the movie has no time to really understand him.

“Music Box” is a vehicle for the Jessica Lange character, and so the old man, who should be the central character if this movie took itself seriously, is only a pawn.

The Lange performance is very good – as strong as her work in “Frances,” for example – and yet Costa-Gavras and Eszterhas have let her down, too. They have put her into a thriller in which there can be no real suspense and provided her with a lot of emotional scenes that we look at in a detached way, because we have figured out the plot and her character has not. Nazis make convenient villains in the movies, because to call a man a Nazi is to save yourself any further trouble in establishing him as evil. The problem in a movie like this is that any intelligent audience member can run through the possibilities as I did above, and see that unless it is going to be about careless mistakes by Nazi-hunters, the story has only one destination.