At some point during the past decade, stand-up comedy became a spectator sport – a struggle of the will between comedian and audience. Comedians began to see themselves as heroic figures, as indeed they probably were, especially in those comedy clubs where the audience sits there getting progressively sloshed while the management throws comedians at them like tag-team relays. The rewards are great: a slot on the “Tonight Show,” a cable special, maybe someday Jay Leno’s job. But failure can be brutal. You “die,” the comedians say. You’re up there, and the audience isn’t laughing, and your intestines are in a vise.

“Mr. Saturday Night” is about a comic like that from an earlier generation, a man with more talent than most, but less judgment.

Spawned in the living room before an audience of adoring relatives, trained in the Borscht Belt, given a shot at his own Saturday night program on CBS, he has blown one opportunity after another, until now at last he is reduced to appearing before the residents of retirement homes.

His problem is he has a gift for alienating audiences. He won’t stick to the script. He does things his way, and it’s the wrong way, as when his TV show begins to slip in the ratings because it’s up against “Davy Crockett.” So what does he do? Makes jokes about how Davy, and everybody else at the Alamo, was probably gay. In 1956, that’s not what people want to hear.

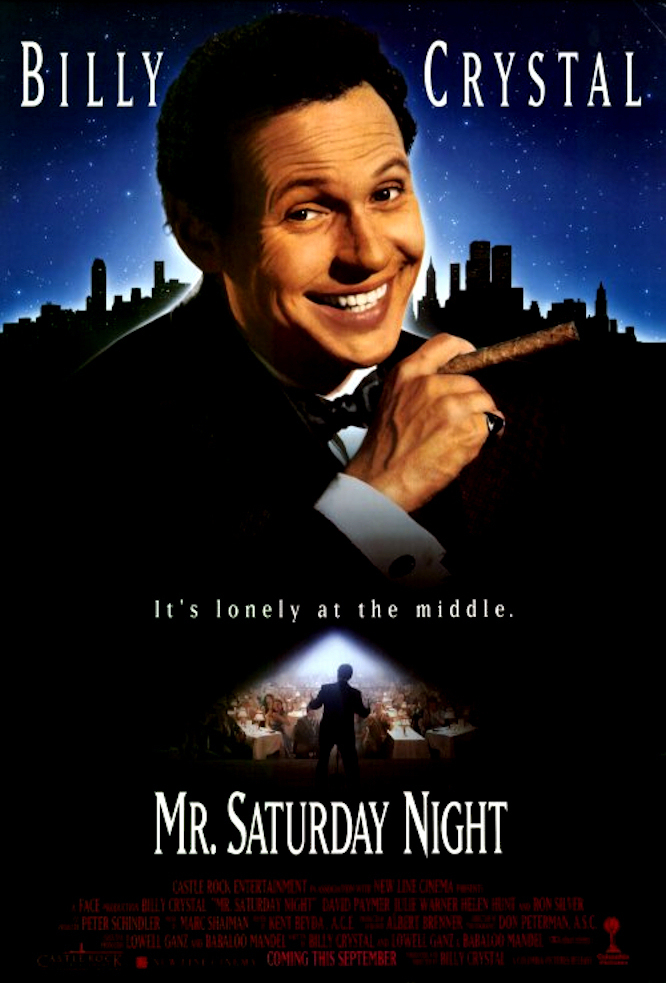

The character’s name is Buddy Young Jr., and he is played by Billy Crystal as an aging tortoise with a big cigar. He has no self-awareness. He uses people. He won’t listen to good advice. He’s dying out there. One of his problems – one the movie only implies – is that Buddy lacks a genuine sense of humor. He knows formulas, gags, “material,” and he uses them on audiences like tools to make them laugh. Because he doesn’t genuinely feel the audience, his feedback is bad; he can’t tell when he’s bombing until it’s too late.

Billy Crystal himself is a different kind of comedian, one who is genuinely funny, who works within the moment, on the audience’s wavelength, but he must have seen a lot of guys like Mr. Saturday Night, and maybe he made this movie as a form of exorcism. It’s a very personal project; he not only stars, but co-wrote the screenplay and makes his directing debut. This is like an autobiography of how he might have turned out.

The movie follows Buddy from his childhood, when he and his brother, Stan, perform for the relatives after holiday feasts. When they enter a talent show, however, Stan hangs back, and Buddy goes solo, and that’s the way it is with them all through their lives, as Stan puts his own plans on hold to manage Buddy. Stan is played as an adult by David Paymer, in a heartbreaking performance that provides the context for Buddy’s long and unhappy life. Stan is smarter. He knows what will work. He sees Buddy destroying himself, and yet is helpless to stop him, because Buddy runs right over him – steamrollers everybody.

The movie makes the usual stops we expect in a biopic about a comedian. We see the summer resorts, the stage shows, the backstage frenzy of early network television. We are there for the courtship of the wife (Julie Warner), who is warmer, nicer and more longsuffering than Buddy deserves.

As the movie opens, Buddy is in crisis. A cruise ship has canceled his booking for the entire winter. The old folks in the retirement homes have stopped laughing. His brother wants to retire.

When he is offered a hot young agent (Helen Hunt), he won’t listen to her – even when he gets a chance to appear as an old comic in a new movie by a Spielbergian director (Ron Silver).

All of this has a real poignancy. What doesn’t really work in the film is the change of heart, which is obligatory, I guess, in all showbiz films, and comes when Buddy has an awakening and realizes he has not been a nice guy. My notion is, anyone who has been a SOB until the age of 70 is unlikely to reform. And so the “happy ending” is unhappy, because it’s not convincing. A truly poignant ending would have cheered me more.

Crystal plays Buddy with love and perception, finding the rhythms of the old comedian, combining them with the double-reverse irony of Borscht Belt humor. He is especially good at showing us the mechanism of Buddy’s self-destruction, that moment when success is offered to him and he stiffens and bristles and snatches failure out of the air.