After the funeral is over and the mourners have come back to the house for coffee and cake and have all gone home, the parents and the boyfriend of Diana, the dead girl, sit by themselves. Her mother criticizes how one friend expressed her sympathy. And the father asks, what could she say? “Put yourself in their shoes.” That little scene provides a key to Brad Silberling’s “Moonlight Mile.” What do you say when someone dies–someone you cared for? What are the right words? And what’s the right thing to do? Death is the ultimate rebuke to good manners. The movie, which makes an unusually intense effort to deal with the process of grief and renewal, is inspired by a loss in Silberling’s own life. The TV actress Rebecca Schaeffer, his girlfriend at the time, was killed in 1989 by a fan. Silberling has grown very close to her parents in the years since then, he told me, and more than a decade later he has tried to use the experience as the starting point for a film.

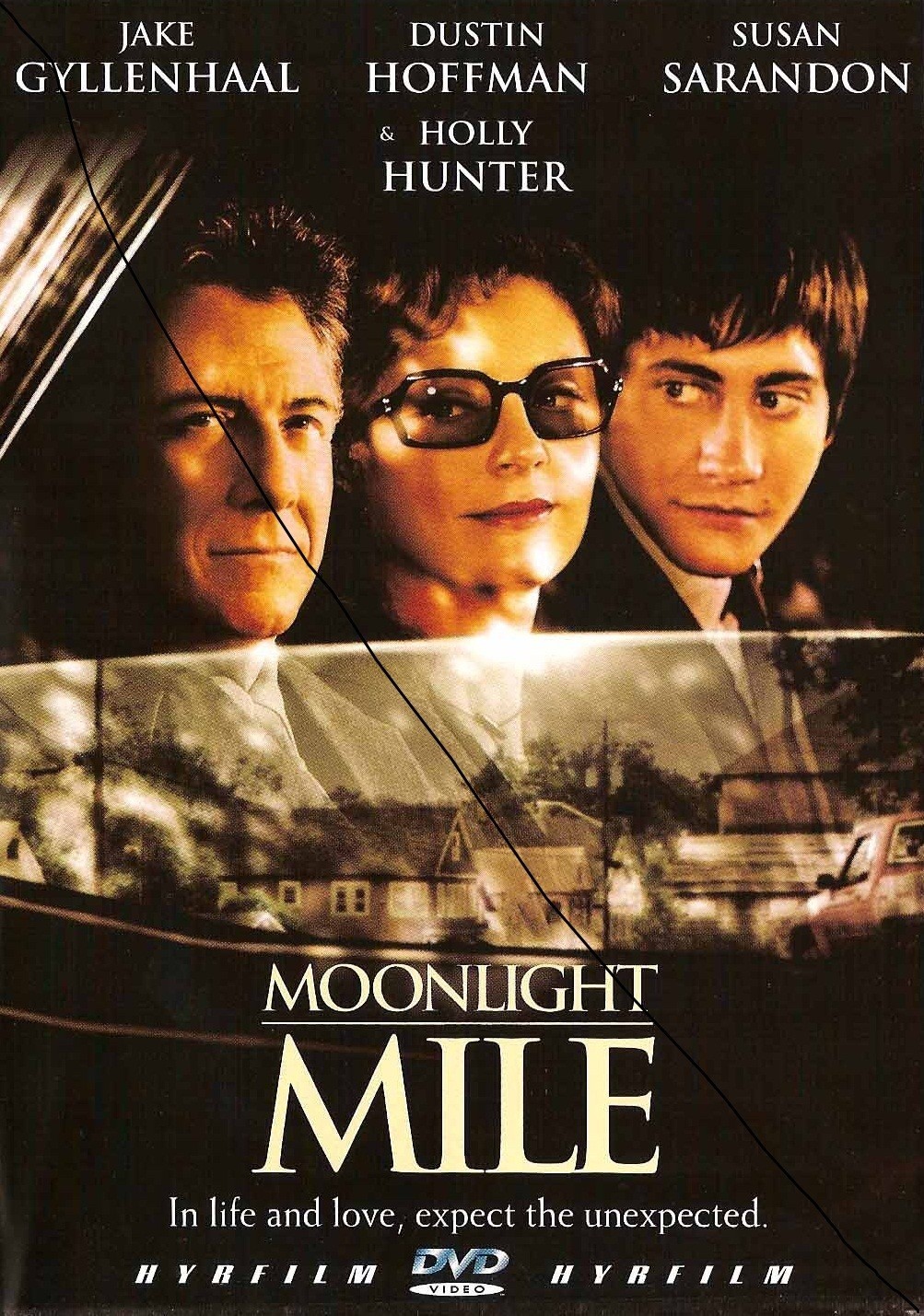

“Moonlight Mile,” which takes place in 1973, opens in an elliptical way. At first only quiet clues in the dialogue allow us to understand that someone has died. We meet Joe Nast (Jake Gyllenhaal), the fiance of the dead girl, and her parents Ben and JoJo Floss (Dustin Hoffman and Susan Sarandon). They talk not in a sentimental way, but in that strange, detached tone we use when grief is too painful to express and yet something must be said.

After the funeral and the home visitation, the film follows what in a lesser film would be called the “healing process.” “Moonlight Mile” is too quirky and observant to be described in psychobabble. Joe stays stuck in the Floss house, living in an upstairs bedroom, his plans on hold. Ben, who has lost a daughter, now in a confused way hopes to gain a son, and encourages Joe to join him in his business as a real estate developer. JoJo, protected by intelligence and wit, looks closely and suspects a secret Joe is keeping, which leaves him stranded between the past and future.

Gyllenhaal, who in person is a jokester, in the movies almost always plays characters who are withdrawn and morose. Remember him in “Donnie Darko,” “The Good Girl” and “Lovely & Amazing.” Here, too, he is a young man with troubled thoughts. At the post office, and again at a bar where she has a night job, he meets Bertie Knox (Ellen Pompeo), who sees inside when others only look at the surface. They begin to talk. She has a loss, too: Her boyfriend has been missing in action in Vietnam for three years. While it is possible that they will mend each other’s hearts by falling in love, the movie doesn’t simple-mindedly pursue that plot path, but meanders among the thoughts of the living.

Silberling’s screenplay pays full attention to all of the characters. Ben and JoJo are not simply a backdrop to a romance involving Joe and Bertie. The movie provides key scenes for all of the characters, in conversation and in monologue, so that it is not only about Joe’s grieving process but about all four, who have lost different things in different ways.

Anyone regarding the Hoffman character will note that his name is Benjamin and remember Hoffman’s most famous character, in “The Graduate.” But Joe is the Benjamin of this film, and Hoffman’s older man has more in common with another of his famous roles: Willy Loman, the hero of “Death of a Salesman.” Ben occupies a low-rent storefront office on Main Street in Cape Anne, Mass., but dreams of putting together a group of properties and bringing in a superstore like Kmart. This will be his big killing, the deal that caps his career, even though we can see in the eyes of the local rich man (Dabney Coleman) that Ben is too small to land this fish. Ben’s desire to share his dream with his surrogate son, Joe, also has echoes from the Arthur Miller tragedy.

Sarandon’s JoJo is tart, with a verbal wit to protect her and a jaundiced view of her husband’s prospects. The deepest conversation JoJo has with Joe (“Isn’t it funny, that we have the same name?”) is about as well done as such a scene can be. She intuits that Joe is dealing not only with the loss of Diana’s life but with the loss of something else.

Pompeo, a newcomer, plays Bertie with a kind of scary charisma that cannot be written, only felt. She knows she is attractive to Joe. She knows she likes him. She knows she is faithful to her old boyfriend. She is frightened by her own power to attract, especially since she wants to attract even while she tells herself she doesn’t. She is so vulnerable in this movie, so sweet as she senses Joe’s pain and wants to help him.

Holly Hunter is the fifth major player, as the lawyer who is handling the case against Diana’s killer. She embodies the wisdom of the law, which knows, as laymen do not, that it moves with its own logic regardless of the feelings of those in the courtroom. She offers practical advice, and then you can see in her eyes that she wishes she could offer emotional advice instead.

“Moonlight Mile” gives itself the freedom to feel contradictory things. It is sentimental but feels free to offend, is analytical and then surrenders to the illogic of its characters, is about grief and yet permits laughter. Everyone who has grieved for a loved one will recognize the moment, some days after the death, when an irreverent remark will release the surprise of laughter. Sometimes we laugh, that we may not cry. Not many movies know that truth. “Moonlight Mile” is based on it.