There’s a musical group based in the U.K. that calls itself AMM; its output is improvised music, as in entirely improvised: the members go on to a stage or (more rarely) into a recording studio and take up their instruments and begin playing. They don’t discuss a plan before (or do much assessment after); they just conjure the music from out of the air. As the group has been at it for some time, the results have taken on a certain character that’s recognizable if not pin-downable. No one else can approximate just what they do. Assessing their recorded output, one critic has said “AMM albums are as alike and unalike as trees.”

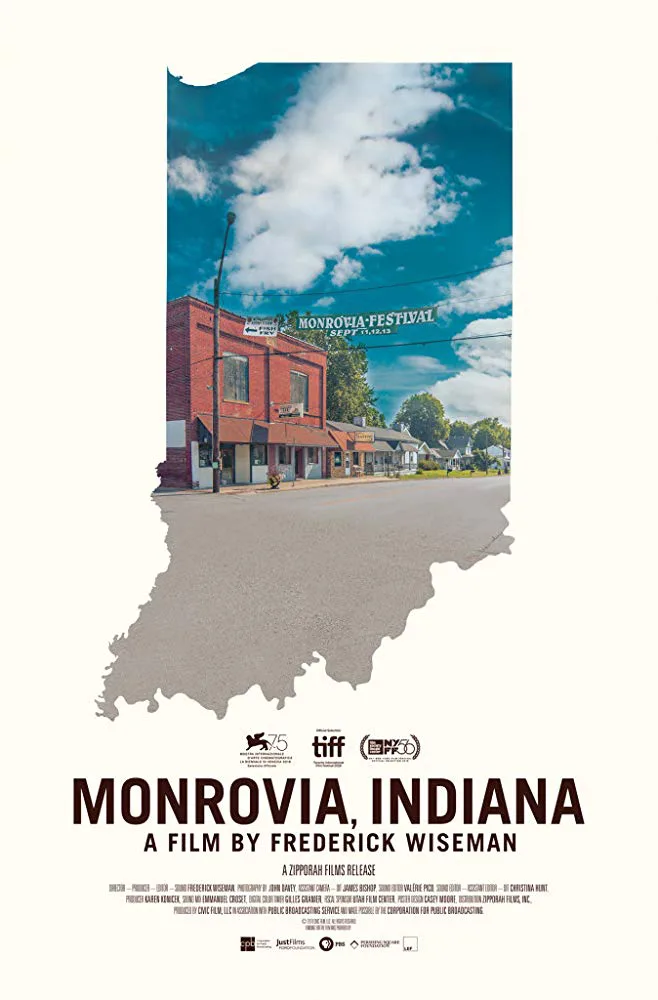

You could say the same thing about the films of the American director Frederick Wiseman. Over the course of more than 50 years, Wiseman has been shooting and editing nonfiction films that situate the viewer in a specific place, one that more often than not is described/named in the film’s title: “Juvenile Court,” “Central Park,” “Belfast, Maine.” Notable exceptions include his debut feature, “Titicut Follies,” a revelatory, scandal-generating film about a Massachusetts mental hospital; that picture got its name for the talent show put on by the hospital’s inmates.

These movies have no narration to orient the viewer; there are no talking head interviews in which subjects address the camera. Wiseman’s shots bring the viewer into the locale, and settle on a few key functions of that place. For 2011’s “Crazy Horse,” about the titular erotic-theatre night club in Paris, the viewer learned about the preparation that goes into the elaborate displays of naked women that make up a seasonal show there. For 2014’s “National Gallery,” Wiseman went behind the scenes at administrative meetings where various requests from outside bodies for use of London’s National Gallery formed a querying subtext about what the function of a museum ought to be in the postmodern world.

Wiseman’s recent works have tended to be near-epic in length—his last two films, 2015’s “In Jackson Heights” and 2017’s “Ex Libris: New York Public Library” both clocked in at over three hours each—but marathons aren’t a given in his work. Indeed, many of his early films are less than 90 minutes long. This one is a hair under two and a half hours.

It is, immediately, a little more quiet than a Wiseman film customarily is. He shoots wide open spaces and narrow streets in this midwestern town, smack dab in the middle of its state, with a population of a little more than 1,000 souls.

The film alights on a few locales. Its high school, where the marching band plays the theme from “The Simpsons,” and a basketball coach recounts NCAA glory days, has an auditorium named for legendary coach Branch McCracken. If you’ve seen the fiction film “Hoosiers” you know how seriously Indiana takes its basketball.

The film also frequently visits meetings of a town planning council, where there is much impassioned discussion of fire hydrants, non-functioning fire hydrants planted by a housing development that seems to have aroused much suspicion among old-time town residents, and so on.

Also: A truck loads up a huge amount of corn, drives to another facility, dumps that corn into a converting mechanism of some kind; the camera only shows, never tells, so unless you are knowledgeable about what’s being manufactured here, the process is completely mysterious.

No one talks politics on a national level. Trump is never mentioned. At the end there’s a street fair where the film lingers on some racist and sexist decals sold by one vendor but otherwise there’s very little observation that approaches editorializing. That might surprise viewers who expected an urban-dwelling filmmaker such as Wiseman to come in and thumb his nose at middle Americans. But Wiseman himself is also the last person who’d call his films “objective,” because they’re not. It’s more that their point of view is multi-faceted, sophisticated, connoting a perspective that’s deeply felt but not on-the-nose obvious.

Wiseman’s portrait reveals emptiness that’s subtle and unforced but becomes devastating. His depictions of activity at a couple of restaurants, one a pizzeria, on the town’s main drag, show a social/civic life that’s enervated and drab. For some reason, the town seems to be drained of energy.

The movie also dwells on death. Its final scene is of a funeral, from a pastor’s sympathetic but occasionally unctuous homily all the way to burial. The long, merciless shots of backhoe and dump truck moving the dirt on top of the grave after the casket has been lowered and the mourners dispersed are haunting. Wiseman, who customarily mans one camera, oversees the audio mix and edits his films, is 88 years old now; despite its lack of overt subjectivity, the movie seems preoccupied with mortality in a way that has little to do with its ostensible subject. I hope Wiseman is well and happily at work on his next film. But there’s an implication of a testament here that makes “Monrovia, Indiana” unalike in a poignant way.