Spike Lee’s “Miracle at St. Anna” contains scenes of brilliance, interrupted by scenes that meander. There is too much, too many characters, too many subplots. But there is so much here that is powerful that it should be seen no matter its imperfections. There are scenes that could have been lost to more decisive editing, but I found after a few days that my mind did the editing for me, and I was left with lasting impressions.

The story involves four African-American soldiers behind enemy lines in Italy in World War II. It’s a story that needs telling. It begins with an old black man looking at an old John Wayne movie on TV, and murmuring, “We fought that war, too.” The next day, he goes to work at the post office and does something that startles us. The movie will eventually explain who he is and why he did it. But in a way we don’t need that opening scene, and we especially don’t need the closing scene, not the way it plays, when a man walks slowly toward a seated man on a beach. The problem is, the wrong man is doing the walking.

You may disagree. There is one “extraneous” scene that is absolutely essential. While in the Deep South for basic training, the four soldiers are refused service in a local restaurant, while four German POWs relax comfortably in a booth. Such treatment was not uncommon. Why should blacks risk their lives for whites who hate them? The characters argue about this during the movie, after boneheaded decisions and racist insults from a white officer. One has the answer: He’s doing it for his country, for his children and grandchildren, and because of his faith in the future. The others are doing it more because of loyalty to their comrades in arms, which is what all wars finally come down to during battle.

“Miracle at St. Anna” has one of the best battle scenes I can remember, on a par with “Saving Private Ryan” but more tightly focused in a specific situation rather than encompassing a huge panorama. The four soldiers find themselves standing in a river, with a Nazi loudspeaker blasting the sultry voice of “Axis Sally,” who promises them sexy women and racial equality in Germany. Their white superior officer orders artillery strikes on their position because he can’t believe any blacks could have possibly have advanced so far. Then the Nazis open fire. The visceral impact of the episode is astonishing.

The four who survive find themselves in a small hill village. They are Stamps (Derek Luke), cool and collected; Cummings (Michael Ealy), a skirt-chaser; Negron (Laz Alonso), a Puerto Rican, and Train (Omar Benson Miller), a towering man with the gentle simplicity of a child. Train has picked up the head of a statue from Florence and carries it with him because he believes that dubbing it makes him invulnerable.

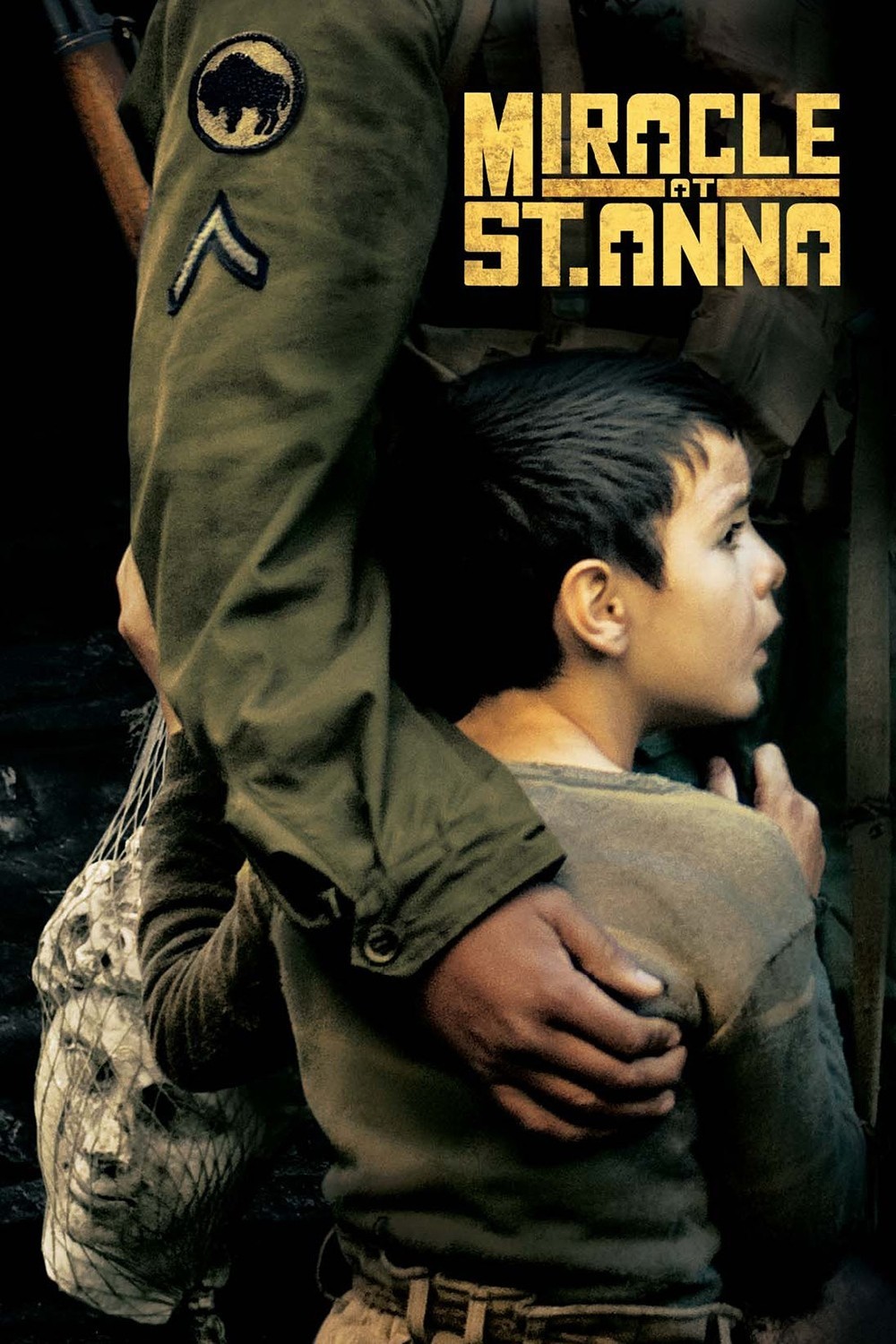

Among the Italians they meet are three important ones: Angelo (Matteo Sciabordi), a young boy who Train saves from death; Renata (Valentina Cervi), a daring and attractive village woman, and Peppi (Pierfrancesco Favino), known as the Great Butterfly, who is a leader of the region’s anti-Nazi partisans. All the characters and all the villagers are involved in another battle scene fought in the village’s steep pathways and steps. Both fire fights are choreographed with immediate visceral effect.

The story of the bond between Train and the boy Angelo seems like material for a different movie. Yes, it involved me, but it seemed to exist on the plane of parable, not realism. It involves a shift of the emotions away from the surrounding action. The acting is superb. Omar Benson Miller (not actually as tall as the movie makes him seem) feels responsible for the boy because he saved his life, and the two form a bond across the language barrier. Matteo Sciabordi, in his first performance, is a natural the camera loves. I can imagine an entire feature based on these two, but I am not sure this story, seen this way, could have taken place in the reality of this film.

Another scene I doubted is an extended one involving a dance in the local church, with music playing loudly, GIs standing illuminated in an open doorway, just as if they weren’t behind enemy lines and the hills weren’t possibly crawling with Nazis. The romantic developments during that scene would have seemed more at home in a musical.

In a sense, the scenes I complain about are evidence of Lee’s stature as an artist. In a time of studios and many filmmakers who play it safe and right down the middle, Lee has a vision and sticks to it. The scenes I object to are not evidence of any special perception I have. They’re the kind of scenes many studio chiefs from the dawn of film might have singled out, in the interest of making the film shorter and faster. But they’re important to Lee, who must have defended them. And it’s important to me that he did. When you see one of his films, you’re seeing one of his films. And “Miracle at St. Anna” contains richness, anger, history, sentiment, fantasy, reality, violence and life. Maybe too much. Better than too little.