As the new Europe edges uncertainly toward its future, the parts uneasily eye the whole. There are not only the obvious problems of language and culture, but also ideas about work and love and art.

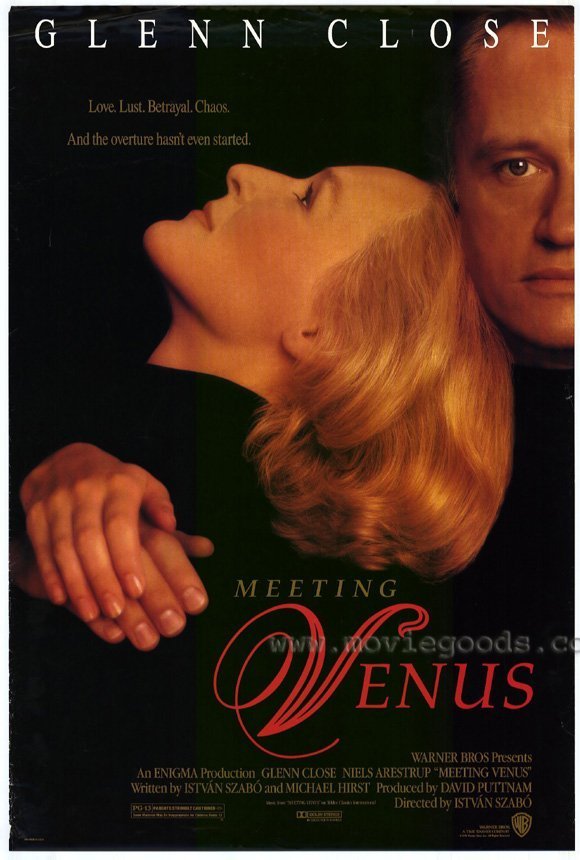

“Meeting Venus” uses an international opera production as a way of showing them all in collision.

The story takes place in Paris, where a new production of “Tannheuser” is contemplated. The conductor (Niels Arestrup) is from Hungary. The diva (Glenn Close) is a temperamental superstar from Sweden. The baritone is a rotund East German who thinks mostly about obtaining hard currency to use in his auto-painting business. When his voice fails, his substitute is an insipid American who is constantly reminded of how things were done differently, and better, in previous productions he has been involved in.

And then there are, of course, the musicians, and the members of the chorus, and the stagehands and electricians and painters and property masters, all members of unions that are ferociously protective of their contracts. And in the front office, management tries to keep everyone happy by taking no clear position on anything.

I imagine that if grand opera were really like this, there would not be any of it. On the other hand, productions and whole seasons are lost because of labor disputes, and the realism of “Meeting Venus” begins to shade over into the satire of “This Is Spinal Tap” in the sequence where the right union man cannot be found to press the button to raise the curtain.

The position of the Hungarian conductor must have been inspired in some ways by the position of this film’s director, Istvan Szabo. He is the leading contemporary Hungarian director (with credits such as the superb “Mephisto“), but now, with the collapse of state subsidies and the opening of Eastern Europe, he, like his character, must learn (in the words of Robert Altman) to fiddle on the corner where the quarters are.

In the film, the director tries vainly to keep everybody happy all of the time, and finds that his duties apparently include an affair with Glenn Close, who is quite sincere and actually very touching during their sweet little love affair, although eventually he, and we, begin to speculate that this is not the first time this diva has gone to bed with her conductor.

There are dozens of major and minor characters in the film, and Szabo juggles them artfully, telling some of their stories and transient flirtations in asides and background action. Meanwhile, the conductor, who is married, finds himself back in Budapest with his wife and his new mistress both at the same time, and the messiness of reality begins to interfere with the unreal backstage world of the opera.

The music in the film is of a high level (Close is dubbed by Kiri Te Kanawa), but there is not very much of it, and indeed we see little of “Tannheuser.” That isn’t the point. The point may be that opera, with all of its romance and coincidence, cannot approach the absurdity of life. Or it may be that through art Europe must find its common destiny. If that is so, Szabo seems to argue, it will not be an easy task.