For centuries, the Greatest Story Ever Told had it wrong. Mary Magdalene, one of the most recognizable women in the Gospels, was not a prostitute, but an Apostle just like Peter, Matthew, or Judas. It was Pope Gregory back in 591 who started this misrepresentation, which wasn’t fully addressed by the Vatican until 2016, when they restored Mary back to her place as one of the most important people in Jesus’ circle. That is an extraordinary correction—whether one considers the narrative to be history or just a story—and it is propagated here by an extraordinary film.

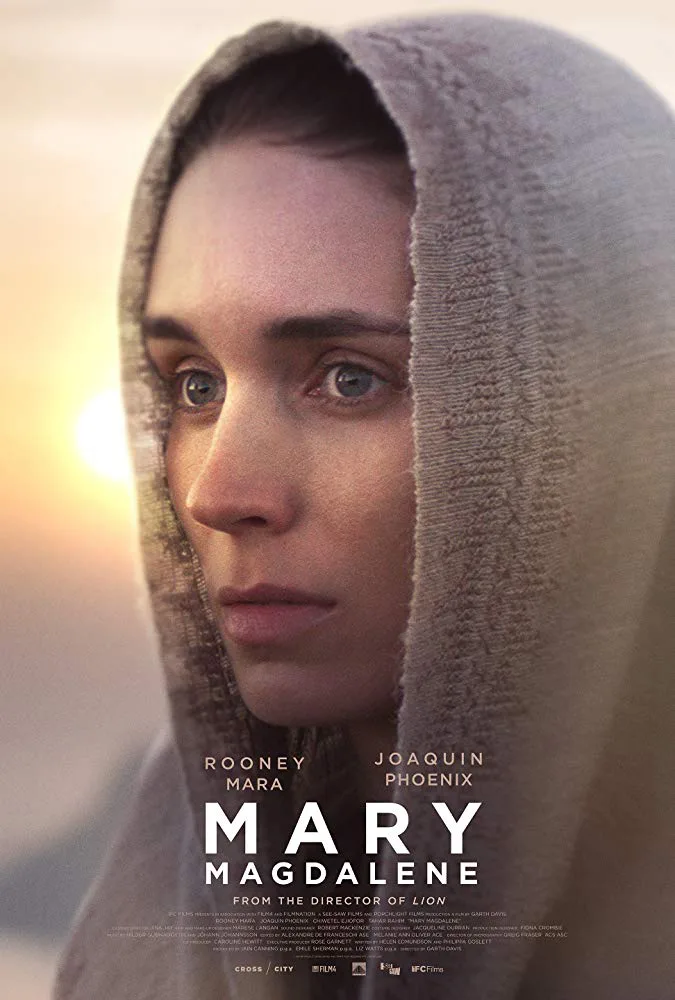

Written by Helen Edmundson and Philippa Goslett, Garth Davis’ “Mary Magdalene” is about the quasi-maniacal dedication of followers and the anguish of a messiah, as presented through a woman’s experience. Rooney Mara plays the title character with a quiet delicacy, often observant as Mary finds a place in the world and a cause in which to place her profound empathy. She was not just any spectator, this telling argues, so much as proof that at the core of Jesus’ teachings is a feminine influence.

At the beginning of the film, Mary wants a choice with her body and her life—she does not want to be simply married off and reproduce, as expected by her brothers and father. At the same time, Mary is not welcomed in the same worshipping space as the men, despite the importance of faith in her life. Her brothers and father deduce that she needs a forced exorcism and nearly kill her by drowning. Mary finds an out when a healer named Jesus (Joaquin Phoenix) comes to town, and decides to become one of his followers. Mary’s connection with Jesus is unlike the ones he has with the men (including Chiwetel Ejiofor‘s Peter and Tahar Rahim‘s Judas), in part because she understands that the kingdom Jesus talks about does not concern splattering Roman blood, but in sharing love.

“Mary Magdalene” does not have any major beats regarding Jesus and the Apostles that anyone who has studied the story would not know. Christ gains a following performing the miracles like bringing a dead man back to life, with Greig Fraser’s handheld cinematography immersing us in hysterical crowds that feature new believers. And once Jesus’ followers speak loudly enough about him being a messiah, a term he lives in fear of throughout, the Romans crucify him. With Davis’ editing gradually focusing on Jesus without losing sight of Mary, “Mary Magdalene” creates a definitive, rich foundation of raw compassion, where many of its scenes rely on simply what you feel from seeing their acts of mercy. The film compels you to look past previous iterations, and to engage the overall tale for its bizarre beauty: a radical movement, led by a tormented man of select words, who speaks of a kingdom that human beings can make a reality. As someone who watched it twice in 24 hours, “Mary Magdalene” moved me in a way that no previous film about Christianity ever has.

Mara is excellent in a role that displays her precision in her acting and reacting—she is the most subdued actor in the entire movie, but that does not make her work any less powerful. In the film’s more contemplative moments, she creates a compelling inner life. Listening, witnessing. But when Davis’ editing does focus more on her, interacting with the elated Apostles or the downtrodden Jesus, it is the work of a full character, created mostly in silence. Mara has a very emotional scene in which she and Peter care for people who are dying from starvation, and the mercy that she communicates as Mary is stunning.

In one of the best portrayals of Jesus these eyes have ever seen, Phoenix is more inspired by the likes of Rasputin, Charles Manson, and the Baghwan than previous Christ imagery. Shaggy, beat, but able to do things like make the blind see, Phoenix’s Jesus is a human being who is visibly tormented by the power and wisdom that works through him. It’s an incredibly physical approach to such a famous being: no word is wasted as his frail voice comes through clenched teeth, his head often tilted back when sermonizing as if trying to maintain balance. And within Phoenix’s own career, it recalls his animalistic nature of Freddie Quell in “The Master,” a blind follower. Now, it is the magnetic expression of a leader with an immense power behind his sharp eyes and careful words, who performs miracles as if he is doomed to it.

There is a strong, crucial sense of mania within “Mary Magdalene” and its vision of a movement. Tahar Rahim and Chiwetel Ejiofor, especially—both who could lead biblical epics of their own—say the words of the Apostles that we know, but with such a bursting exuberance that we know they’ve completely drunk the Kool-Aid, and then some. These men are so desperate for a resolve to their pain, as Mary learns in her quiet, haunting conversations with them, that their lives have become an open-arms embrace for a kingdom that’s only as real as their faith. This is never seen as a criticism against the Apostles—instead it’s an incredibly honest take on full-fledged worship, and another example of the staggering compassion that “Mary Magdalene” has for the people in its story, and what they represent.

“Mary Magdalene” is a film I wish I had when I was taking religion classes, and also film classes. Davis poignantly uses the holiest of cinematic expressions, the magic hour—that time in between night and day when the sky is a watercolor mix of purple, orange, and pink, revealing a type of complex beauty before it evolves to darkness or light. The power in “Mary Magdalene” often starts with its imagery, which builds from its appropriately barren huts and monochrome costumes to make you appreciate how natural light is a nuanced expression itself. When characters speak on calm cliff sides as the day turns to night, as they often do here, it only compels you to engage the film in a deeper way.

The music of “Mary Magdalene” is significant on its own, but it has an added, sorrowful importance: it’s the last film score by the late Jóhann Jóhannsson, who is co-credited with cellist Hildur Guðnadóttir. Jóhannsson was a composer whose power came from his ability to create precise atmosphere with rhythm and melody, regardless of the project. “Mary Magdalene” is a strong testament to Jóhannsson’s meticulous arrangements, his mournful string pieces paired with howling winds and prayers, further coloring Fraser’s extreme wide shots that show Jesus’ followers as seeds in a barren land.

“Mary Magdalene” is one of those movies in which numerous passages feel weightless, the culmination of so many vivid filmmaking entities contained in one picture. Simultaneously gorgeous and eye-opening, the film uses its grace to preach about the potential of storytelling—especially when it comes from an underrepresented perspective. Davis’ movie contemplates miracles and acts of love I’d heard about during a countless amount of hours at Sunday mass and beyond. But through the profoundly compassionate lens of “Mary Magdalene,” it felt as if I was learning about them for the first time.