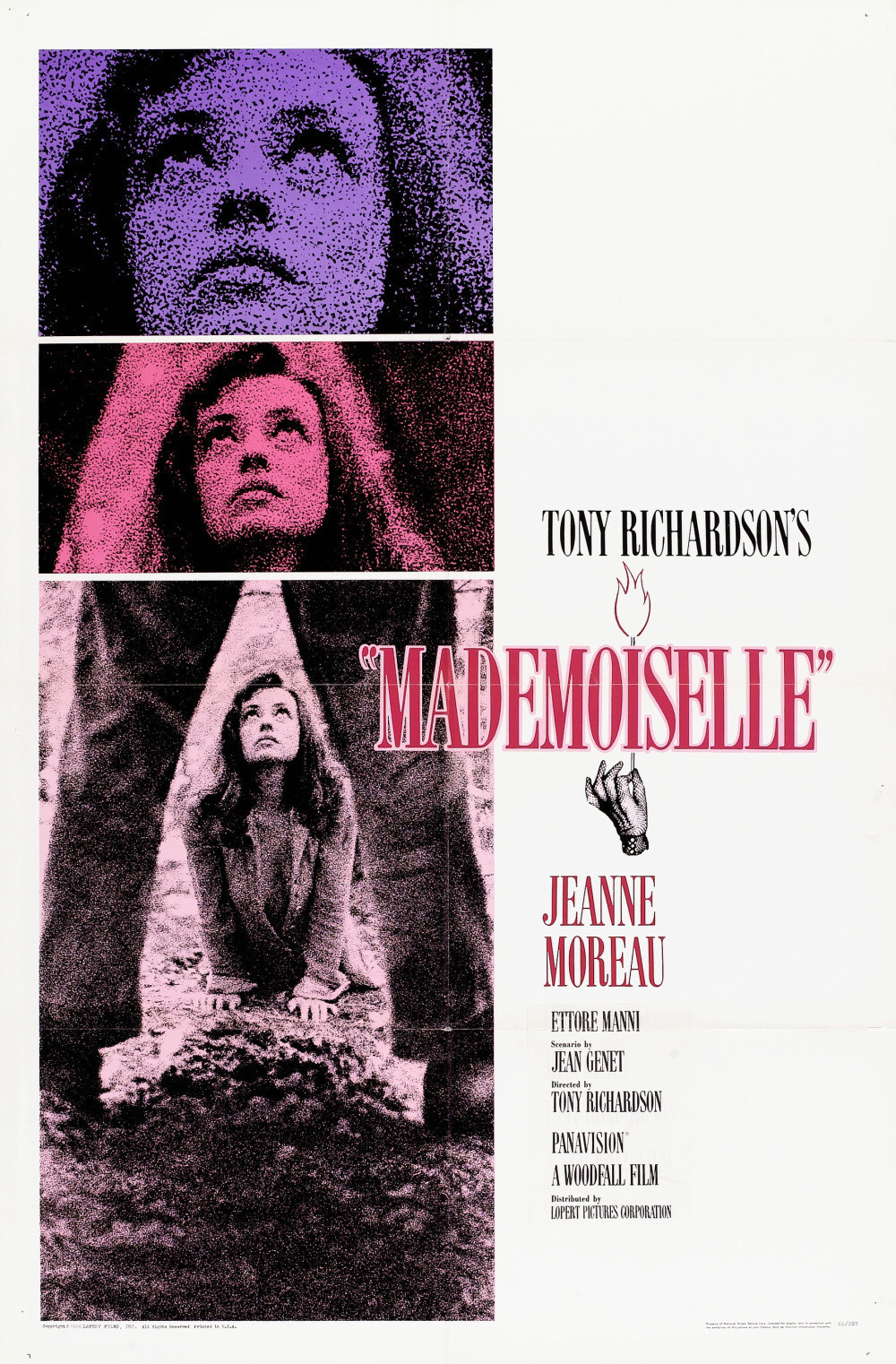

Let’s have a contest, gang. The one who finds the most Freudian symbols in Tony Richardson‘s “Mademoiselle” wins the Norman Vincent Peale book of his choice. I’ll give you a few to get your list started: There are 19 shots of a lake. Lakes stand for women. Sometimes it is stormy, sometimes it is covered with raindrops, sometimes it is calm. Everytime you see Jeanne Moreau, she is like the lake. Stormy, covered with raindrops, calm.

Then there is a great scene where she meets the Italian lumberjack in the woods. He has a pet snake. They shake hands, and the snake crawls down his arm and up hers. For a moment there, while the snake is in midpassage, you could turn the screen on edge and have the trademark of the American Medical Assn.

Then you have Miss Moreau’s hang-up. She is a schoolteacher in a French town. She tells her students a story about an evil baron who sneaks out at night and sets houses on fire. Sure enough, Miss Moreau sneaks out at night and sets houses on fire. She also opens the floodgates on the dam, poisons the water supply and smokes cigarettes. She is an evil woman.

One day she goes out into the woods and is seduced by the lumberjack. The seduction scene lasts from about 4 p.m. until noon the next day. Miss Moreau and the lumberjack run through the fields and the forest and around the lake, and about midnight it starts to rain. Then it gets muddy. They slosh through the mud, carrying on their carefree lovers’ dance. Slosh, slosh, slosh, I hear the lovers dancing.

The town is a very peculiar town. It is a French town in which the Italians speak in English subtitles, and when the French speak, they speak in French to each other, but in English when they are speaking to the camera. Miss Moreau speaks in English and teaches her classes in English, even though she is French. The kids don’t learn so fast. Probably confused by the Italian subtitles.

I am not, of course, being very fair to “Mademoiselle,” but it is not the kind of movie that encourages mercy. It is murky, disjointed and unbearably tedious. The script by Jean Genet reads like something out of Evergreen Review by way of French pornography.

Tony Richardson has never made a movie anything like this before. His best films (“Look Back in Anger,” “A Taste of Honey,” “Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner” and “Tom Jones“) were all characterized by a fast-paced editing style and a refreshing disregard for pretension. But with “The Loved One,” Richardson came down with a bad case of trying too hard, and in “Mademoiselle” there is no restraint at all.

Still, Miss Moreau is as flawless in her lousy roles as her good ones.