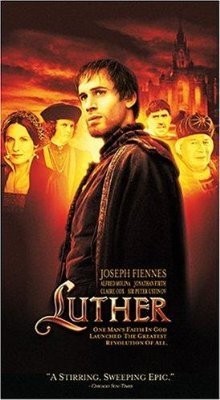

Martin Luther was the moral force of the Reformation, the priest who defied Rome, nailed his 95 Theses to the castle door and essentially founded the Protestant movement. He must have been quite a man. I doubt if he was much like the uncertain, tremulous figure in “Luther,” who confesses, “Most days, I’m so depressed I can’t even get out of bed.” It is unlikely audiences will attend this film for an objective historical portrait; its primary audience is probably among believers who seek inspiration. What they will find is the Ralph Nader of his time, a scold who has all his facts lined up to prove the Church is unsafe at any speed.

Who was Joseph Fiennes channeling when he chose this muddled tone? Obviously he was reluctant to gave a broad, inspirational performance of the kind you find in deliberately religious films. Jesus comes across in some Christian films as a Rotarian in a robe, a tall, blue-eyed athlete who showers every morning.

I remember defending “The Last Temptation of Christ” against a critic who complained that all of the characters were dirty. At a time when most people owned only one garment and walked everywhere in the desert heat, it’s unlikely Jesus looked much like the Anglo hunks on the holy cards.

Martin Luther’s world is likewise sanitized, converted into a picturesque movie setting where everyone is a type. The movie follows the movie hat rule: The more corrupt the character, the more absurd his hat. Of course Luther has the monk’s shaven tonsure. He’s one of those wise guys you find in every class, who knows more than the teacher. When one hapless cleric is preaching “there is no salvation outside the Church,” Luther asks, “What of the Greek Christians?” and the professor is stumped.

The film follows the highlights of Luther’s life, from his early days as a law student, through his conversion during a lightning storm, to his days as a bright young Augustinian monk who catches the eye of his admiring superior, Johann von Staupitz (Bruno Ganz).

He is sent to Rome, where he’s repelled by the open selling of indulgences (Alfred Molina plays a church retailer with slogans like Burma-Shave: “When a coin in the coffer rings, a soul from Purgatory springs”). He’s also not inspired by the sight of the proud Pope Leo XII (Uwe Ochsenknecht), galloping off to the hunt, and when he returns to Germany, it is with a troubled conscience that eventually leads to his revolt.

One thing the movie leaves obscure is the political climate that made it expedient for powerful German princes to support the rebel monk against their own emperor and the power of Rome. In scenes involving Frederick the Wise (Peter Ustinov), we see him using Luther as a way to define his own power, and we see bloody battles fought between Luther’s supporters and forces loyal to the Church. But Luther stands aside from these uprisings, is appalled by the violence, and, we suspect, if he had it all to do over again, would think twice.

That’s the peculiar thing about Fiennes’ performance: He never gives us the sense of a Martin Luther filled with zeal and conviction. Luther seems weak, neurotic, filled with self-doubt, unwilling to embrace the implications of his protest. When he leaves the priesthood and marries the nun Katharina von Bora (Claire Cox), where is the passion that should fill him? Their romance is treated like an obligatory stop on the biographical treadmill, and although I am sure Katharina told Martin many tender things, I doubt one of them was “We’ll make joyous music together.” This Martin Luther is simply not a joyous music kind of guy.

The most fun comes from the performance of grand old Sir Peter as Friedrich, who treasures his collection of sacred relics but sweeps them all aside after Luther casts doubt on their worth and authenticity (Luther has a funny speech pointing out that many saints left behind more body parts than they started out with). Ustinov here reminded a little me of his great Nero in “Quo Vadis,” collecting his tears in tiny crystal goblets — a big boy, playing with the toys of power.

Another major role is the papal adviser Cirolamo Aleandro (Jonathan Firth), who correctly sees the threat posed by Luther and demands his excommunication and punishment, but, for a political insider, misjudges the climate among the princes of Germany. The movie makes it clear to us, as it should to him, that for the power brokers in Germany, Luther’s rebellion has as much secular as spiritual significance: He provides the moral rationale for a break they already desired to make.

I don’t know what kind of movie I was expecting “Luther” to be, or what I wanted from it, but I suppose I anticipated that Luther himself would be an inspiring figure, filled with the power of his convictions. What we get is an apologetic outsider with low self-esteem, who reasons himself into a role he has little taste for.