“Lost Girls and Love Hotels” plays like the result of a collision between “Lost in Translation,” “Looking for Mr. Goodbar” and the entire “Fifty Shades of Grey” saga. Actually, I probably shouldn’t say that because that particular combination of influences is so bizarre that it might actually lure some viewers into seeing it on the theory that, if nothing else, the end result would almost have to be at least somewhat interesting. While there are plenty of words that could be used to describe this attempted combination of introspective drama and kinky sex fantasy, “interesting” is one that I am reasonably sure will not be further deployed in the course of this review.

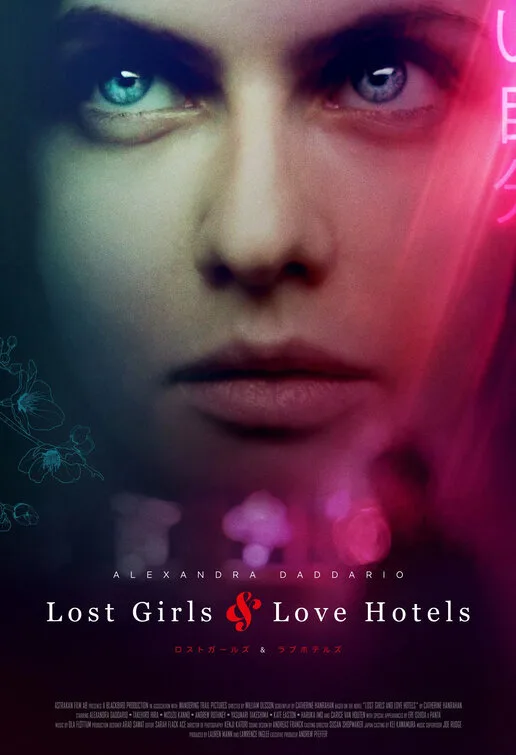

Set in Tokyo, the film centers on Margaret (Alexandra Daddario), a disaffected young woman who spends her days drifting through her job teaching English pronunciation at a Japanese flight attendant training school. At night, she boozes it up with a couple of fellow expats before going out to find a new strange man to take her to a love hotel—a popular form of lodging catering to guests who want someplace to go for a quickie in privacy—for anonymous kinky sex before beginning the cycle anew the next day. One night, she catches the eye of the mysterious and handsome Kazu (Takehiro Hira) and with his familiarity with both the most famous work of artist Hokusai Katsushika (you’ll know it when you see it) and the zip ties he finds in her bag during their first love hotel visit, it seems as if he is perfectly on her wavelength. Even the revelations that he is a member of the yakuza and that he is about to get married have no effect on her other than a couple of questions about the whole notion of chopping off a finger as punishment. It cannot last, of course, and when things eventually change, it sends her on a downward spiral that will presumably lead to either self-destruction or self-realization—in either case, a lot of sheets will need to be cleaned along the way.

“Lost Girls and Love Hotels” was based on a 2006 novel by Catherine Hanrahan and since I have not read it, I cannot say if this is a case of an adaptation doing a gross disservice to the original source material or not, though it should be noted that Harahan herself is credited with the screenplay. As a dark psychological portrait of an unmoored young woman casting herself adrift in a land filled with people she has no connection with and relationships that end when the room rental expires, director William Olsson’s work is astonishingly silly and shallow. It demonstrates all of the emotional awareness of a lesser entry in the “Emmanuelle” franchise—outside of one very awkward scene in which Margaret alludes to her father (absent), mother (dead) and brother (apparent mental issues), we get no insight as to who she is, what makes her tick (so to speak) or why she takes so completely to Kazu other than the fact that the script requires it. The “Emmanuelle” comparisons do not extend to the erotic content, which wants to be seen as edgy and provocative but proves to be as steamy and arousing as a limp udon and as outre as a visit to Spencer’s Gifts. Then there the film’s desperate attempt to try to somehow append a happy ending to all of the gloomy nonsense that has preceded it, and which only fits in the sense that it as just as unlikely as everything else on display.

Alexandra Daddario has proven to be a striking screen presence in the past, most notably on the first season of “True Detective,” but is unable to do anything with the cipher of a character she has been given to work with—she seems almost as lost and adrift as Margaret, albeit for entirely different reasons. In addition, she strikes zero sparks with Hira in their scenes together, which is kind of significant considering that the entire narrative theoretically hinges on the powerful attraction that is meant to exist between them. That said, the biggest casting botch comes with the presence of Carice van Houten, the mesmerizing focus of Paul Verhoeven’s “Black Book” and Melisandre from “Game of Thrones,” in the nothing role of one of Margaret’s drinking buddies. As a fan, I was glad to see her at first but quickly became dispirited when it became painfully obvious that she was not going to be given anything of interest to do—her presence is so utterly superfluous to the proceedings that you have to wonder why she bothered to sign on, other than the lure of a free trip to Tokyo. She winds up leaving long before the proceedings come to their merciful-yet-ludicrous conclusion and when she does, most viewers will want to bail with her as well.

“Lost Girls and Love Hotels” is too vapid to work as a psychological drama, too silly to work as a passionate romance, and too tepid to work as a sexy guilty pleasure. Like its heroine, it sends viewers on a series of increasingly meaningless and unfulfilling encounters but the closest thing to a sense of catharsis that they receive comes only with the arrival of the end credits. To give credit where it is due, I will admit that it does have a grabber of a title. Maybe someone will one day take it and apply it to a movie that deserves it.