Alan Arkin’s “Little Murders” is a very New York kind of movie, paranoid, masochistic and nervous. It left me with a cold knot in my stomach, a vague fear that something was gaining on me. It’s a movie about people driven to insanity and desperate acts of violence by the simple experience of living in a large American city.

It falls somewhere within the category of satire, but Arkin has been careful to keep the satire within very tight and self-consistent boundaries. This isn’t the kind of satire that lets up occasionally, that opens a window to the merely ridiculous (as “Dr. Strangelove” did), so that we can laugh and relax and brace ourselves for the next stretch of painfulness. No, “Little Murders” is entirely self-contained, and once you get inside it, you’ve got to stay.

Arkin said, shortly after the film was released, that he’d only seen his movie once in a theater, and he was afraid to go again. When he saw it with an audience, he said, he thought it was a flop because there was no pattern to the laughs. People were laughing as individuals, almost uneasily, as specific things in the movie touched or clobbered them.

That’s my feeling about “Little Murders.” One of the reasons it works, and is indeed a definitive reflection of America’s darker moods, is that it breaks audiences down into isolated individuals, vulnerable and uncertain. Most movies create a temporary sort of democracy, a community of strangers there in the darkened theater. Not this one. The movie seems to be saying that New York City has a similar effect on its citizens, and that it will get you if you don’t watch out.

Jules Feiffer’s screenplay is about Alfred, “a devout apathist,” who gets by in New York, sort of, by deadening himself to the terrible cries, smells, sights and pains the city keeps lobbing at him like flies and grounders. You can’t feel pain if you can’t feel anything. If the absence of sensation means a living death, then perhaps zombies are merely creatures thrown up by evolution to live in the urban environment.

Alfred, a zombie, meets Patsy, an optimist, who keeps smiling through a wilderness of muggings, snipping, bombings, and obscene telephone calls because if she lets such things get at her, what’d be the use of living? Indeed. Patsy makes her life in New York a happy one, according to her, by consuming fashionable possessions, places and opinions. She introduces Alfred to this glorious existence and, sure enough, the good life breaks through his shell. He falls in love.

This stretch of the movie — Patsy’s courtship of Alfred — contains some awfully interesting ideas about the materialistic society. It seems to be saying that city life has cut its characters off from simple human emotion, and they’ve forgotten how to love or be sorry. Sharp, intense experiences can still penetrate the shell: sex, pain, getting fired. But the gentler emotions have atrophied.

Consumer buying power, however, may be a form of salvation. City dwellers can set out on self-improvement programs designed to restore their emotional muscles. By vacationing at expensive resorts, eating in intimate restaurants, possessing fashionable artifacts, people may actually be able to learn (from objects!) how to be people. It’s significant, here, that Patsy is an interior decorator; she sees her own life largely in terms of the possessions and attitudes she has arranged around it.

The city finally defeats her, however, but not before Alfred finds a harbor in her family. Patsy’s father, mother and brother perform a hysterical parody of “family life,” and Alfred fits right in. He even helps break down their apathy. They’d been content to do merely passive things like install steel shutters on their windows and triple locks on their doors. He buys a rifle and encourages them to start shooting back.

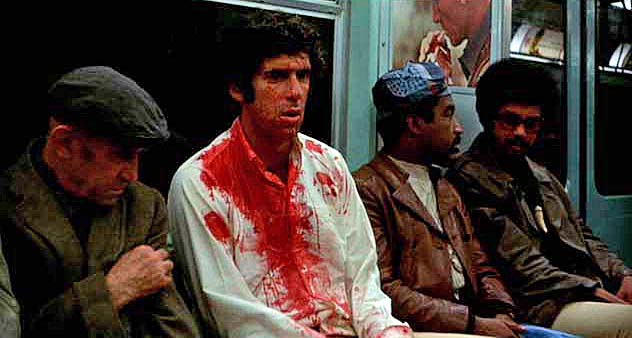

Elliott Gould’s performance as Alfred sets the movie’s acting tone, which is uptight, barely controlled (but somehow low key) hysteria. An illustration would be Donald Sutherland’s brilliant cameo as a progressive minister who uses the concept of love as a bludgeon. Arkin makes “Little Murders” so much of a piece, so consistent on its own terms, that while you’re watching it, it doesn’t even feel like satire: just real life, a little farther down the road.