Bruno Dumont is that French director your friends have warned you about. His characters pontificate about God, death, and evil between being violated and subjugated. He shoots through a lens filter called “abject Gallic misery.” Christ-figures abound and they’re mortified enough for three crucifixions. He’s been mixing Tod Browning, Catherine Breillat and Carl th. Dreyer for over fifteen years and until recently he had but two settings: beautifully troubling and unbearably bleak. It seems however, he’s emptied the suggestion box and realized that perhaps he’d gone as far as his obsessions could carry him in his chosen mode. Maybe seven films without a single laugh was a little much? Well, fear Dumont’s unsettling vision of humanity no more: he’s trawled through his back catalogue (which includes the punishing “Twentynine Palms,” the transcendent “Hadewijch,” and the abstruse “Hors Satan”) and put together a hilarious remix of his greatest hits in the form of a joyfully bizarre 3-hour miniseries. Saying “P’tit Quinquin” is Dumont’s funniest and warmest film doesn’t count for much, but could I interest you in one of the sharpest autocritiques in recent memory? Dumont’s real trick isn’t spinning his iconic imagery for laughs, but doing so without straying from his usual mission of investigating the extent to which humans can possibly be modeled after God in the most violent imaginable terms. That’s having your cake and eating it in ways Lars Von Trier could only dream of.

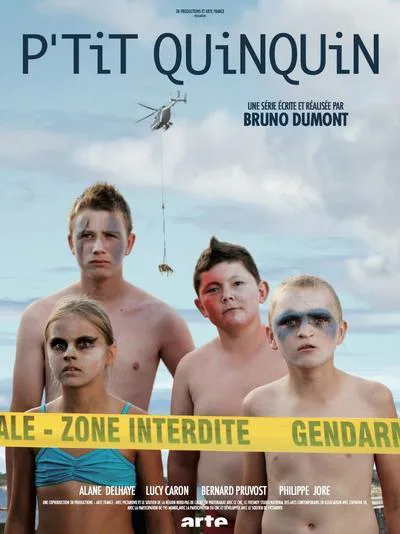

“P’tit Quinquin” begins like the prequel to “Hors Satan” no one in their right mind would ask for, with a young boy (Alane Delhaye, the Quinquin of the title) trying to impress a girl (Lucy Caron) by killing a mouse on a sprawling farm. They make their way to the edge of the property in time to see a murder investigation begin. The body of a woman has been found stuffed inside a dead cow, her head nowhere to be found. The Commandant in charge of the investigation (Bernard Pruvost) notices Quinquin and his friends lurking near the crime scene and makes it his personal mission to bug the angry little kid every chance he gets. The investigation bobs and weaves between the poorest farmer and the highest official in town and Quinquin always seems to be right around the corner whenever a lead is confronted. But for all his proximity to the unfolding case, Quinquin’s world is only ever as big as his pride and racism allow it to be. His chief concern is making his girlfriend feel safer as life keeps throwing them curveballs. Normality crumbles a little more with each new murder and neither Quinquin nor Pruvost’s investigator have a terribly tight grip on their wits.

“P’tit Quinquin” is Dumont’s most nakedly referential work. From the opening shot of a Helicopter carrying a cow, a sacrilegious inversion of “La Dolce Vita“‘s famous shot of Jesus flying over Rome, to the Kaurismakian musical interludes, Dumont seems to be letting conventional work into his mise-en-scene so that those film’s generosity of spirit might help bring the sunshine and smiles out of the poker-faced auteur. As if to prove his willingness to be merry, he replays images from his earlier work: three chubby pale boys taking to the surf in their tight bathing suits and later pursuing a boy through a field yelling racial epithets are both taken from his bracing debut “La Vie De Jesus.” The mentally ill supporting characters from “Camille Claudel 1915” take on vibrant, poignant new life here. The motif of a boy and a girl sharing a bike ride has cropped in half of his movies, and the landscape he’s so fond of remains as mockingly picturesque and forbidding as it always has. Dumont’s attitude toward religion is the same old disaffected prostration it’s always been. As someone in the film says “Let’s split. The Devil Lives Here.” The only thing missing is the gratuitous, ugly sex! Maybe Dumont lost interest in the provocative imagery that scarred up his early films or maybe he’s said all he can, but the work doesn’t miss his usual grotesque intimacy or hideous violence. A film that walks a tonal tightrope this fine could so easily tip over into vulgarity, but Dumont miraculously never once loses his footing.

Dumont’s approach to death is one of the more unique in modern cinema. His character’s unwavering focus on death means that if/when they finally die it feels like we’ve just been waiting for them to kick the bucket, which perhaps explains why, when victim after victim is claimed by the murderer, it still never feels as though there’s a genuine threat lurking nearby. The casual attitude toward death has the curious effect of preserving the emotional continuity of each character’s journey while creating a breezy space where each comic setpieces can exist without interference from reality. The first clue that we’re in new territory comes during the funeral for the first victim, which starts with a priest fussing over his aid’s cassock for a small, hilarious eternity. Alterboy Quinquin refuses to complete one his rituals, forcing the priest into a kind of fitful dance waiting for him to finish, and those are just the most obvious moments. At the risk of hyperbole, it’s got to be among the two or three most comical funerals in motion picture history.

“P’Tit Quinquin” indulges in a half dozen different schools of film comedy, often in a single scene, and the great length of the piece means that repeated gags have time to take root and grow with each appearance. A leitmotif in which Quinquin constantly takes the blame for the few things he didn’t do gets a healthy workout when a boy shows up on his farm dressed in what he imagines to be Spiderman’s costume, but what is actually just absurdly layered pajamas. He runs around shouting “Speedyman” and pretending to shoot webs out of his hands, which means he didn’t quite get the gist of whatever version of the Marvel hero he was exposed to. Quinquin is angry and confused, but he’s just transfixed enough by the strange sight that he can’t quite move to stop the boy from behaving this way. By the time “Speedyman” has returned and disoriented Quinquin’s disabled cousin, it’s far too late. The mischievous little boy is gone before Quinquin’s father shows up asking how his cousin fell over, so naturally Quinquin gets the blame. The icing on the cake of this splendid little vignette? The kid in the Speedyman suit is never explained. He jumps into the film and just as quickly jumps right back out. There’s funny, and then there’s sublimely hysterical.

The thing you’ll remember about “P’tit Quinquin”, over even the most perfectly timed joke or the adorably misshapen head of Quinquin, is the face of Bernard Pruvost, as the detective protecting his flock from the murderer. Pruvost looks like Albert Einstein and has a facial tic that causes his face to move involuntarily in very noticable ways, meaning he delivers something like four reactions for every stimuli and sometimes more. He’s a real-world cartoon in Dumont’s hands, a man who never stifles his attempts at respectability, even though they’re constantly rejected. His attempts at yelling at some kids about highway safety are thwarted when his partner turns their car in the wrong direction with his head still hanging out the window. Upon learning of the state of the first victim, he muses, more to himself than anyone listening: “Headless…so I need the head, basically.” However funny he is, there is an undeniable sadness to Pruvost’s character, a man unable to stop his town from succumbing to the slowly encroaching darkness. A long take late in the film finds him sitting and listening to the church organist play only for him, his face soaking with sadness. He’s as much cop as activist priest, fighting the devil one sin at a time, preserving an innocence that isn’t his to protect. He’s this season’s most offbeat detective, beating out even Joaquin Phoenix’s coke-snorting Doc Sportello in “Inherent Vice.”

And yet there is hope in this grim diagnosis. A half dozen murders, which Dumont drops into the narrative as if they were windows left open, would be normal in most other places. Here they bring Pruvost’s worldview crashing down around him. His claim that the man behind the murders is worse than the devil calls to mind the newspaper that described Jay Gatsby’s murder as a “holocaust”. When you can’t imagine great evil, a small one is bound to knock the wind out of your sails. Dumont is firmly on the side of the angels here, refusing to do much more than spiritual harm to his misguided heroes while God looks the other way. If a suspicious, stubborn old man and a racist little kid can both remember to do the right thing when the devil comes prowling, then tomorrow will be a brighter day indeed. The brightest one Dumont’s ever conjured.