At the end of this movie, before the closing credits, a few screens’ worth of text informs the viewer of the casualty rate of the electrical lineman over the past few years, and gives the name of a website whose mission “is to memorialize fallen electrical line workers, and care for the families who have lost or are impacted by a severe injury of a loved one in the line of duty. We strive to consolidate accident and injury information to share openly for a safer work environment.” Its web address is http://fallenlinemen.org and the site is well worth visiting.

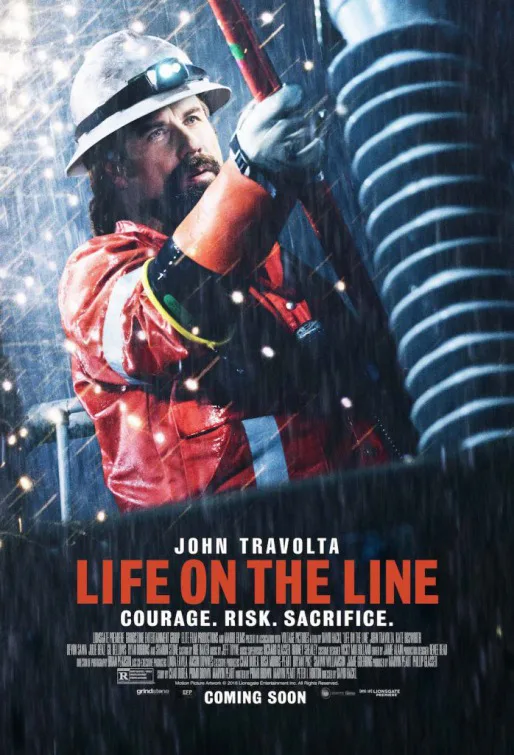

I point this out now because I am obliged to assess the movie that preceded it. That movie does not, I think, do the job it intended, which was, I think, to make the lineman’s work accessible to the viewer and to honor the courage and sacrifice of those who labor to keep the nation’s electrical grid safe and operative. This is one of those “based on true events” movies that give you the distinct feeling that the true events deserved better.

After introducing the framing device of an interview with a lineman played by Devon Sawa, the movie begins again with a prologue set in 1998 Texas, with John Travolta, in unconvincing young-age makeup, as Beau Ginner, a Texas lineman working in the middle of a lightning storm. He fails to rig some wires properly; his coworker, who’s also his brother, chastises him, goes up the pole, and is soon killed after lightning hits a wire. His sister-in-law is killed in an auto accident rushing to the scene. Ginner is left with his memories, his job, and his young niece Bailey, who grows up to be played by Kate Bosworth, who also played the sister-in-law.

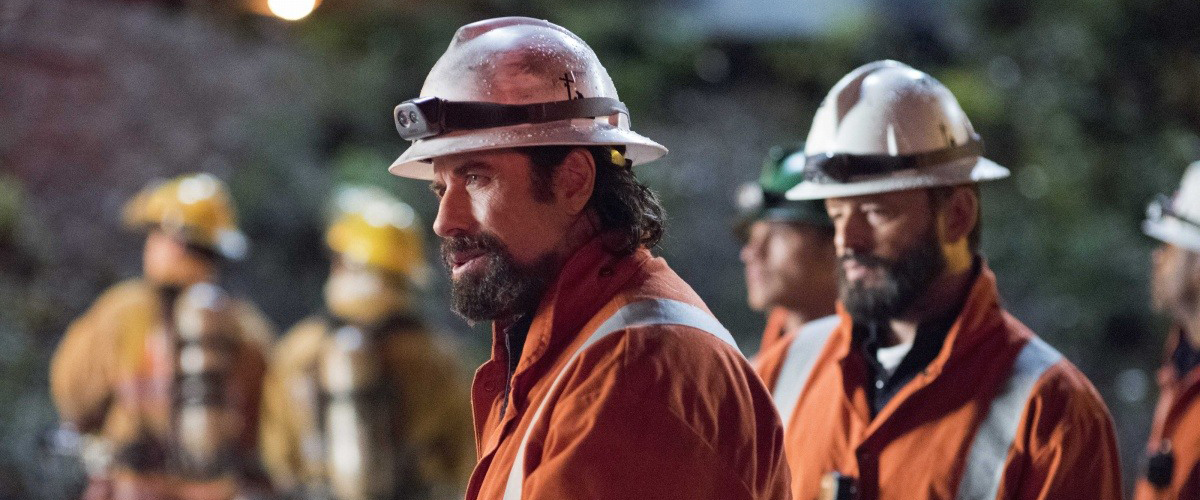

Experience has made Beau a safety maven, and sentiment has made Bailey a ‘round the way girl who has the potential to go to college (one would think so, at age 33, although I guess Bosworth’s playing younger) but prefers to work in a diner and be a townie—which means being part of the lineman extended family. Here is where the narrative complications come in, and boy is director David Hackl not up for them. Here we go: Bailey has a sort-of ex-boyfriend named Duncan (that’s Devon Sawa’s character) who’s a bit of a bad boy, motorcycle and all. (He’s also got an alcoholic mom, a lineman widow, played by Sharon Stone in dampened “Casino” mode.) He’s decided to straighten out, so he gets a job working the line, much to the chagrin of Beau. Then there’s Ron (Matt Bellefleur), a creepy ex of Bailey’s who’s hanging around all sorts of places where he isn’t welcome. Beau and Bailey also have new across-the-street neighbors, Ryan Robbins’ Eugene, a lineman who’s also an Iraq war veteran with PTSD, and his wife Carline (Julie Benz), who’s good-hearted and loyal up to a point, and who picks the wrong way to balk at Eugene’s neglect and borderline abuse. As a major storm approaches their town—you know this because every other scene or so a title comes up saying “[X] Days Before THE STORM,” with graphics like some cable news special or something—the characters abrade each other in various ways, Bailey reveals a secret, and something’s gotta give. In case you missed it, it’s pretty clear that the storm is gonna make everything and more do that giving.

These plot lines aren’t simple, but they’re not exactly convoluted either. Frequently while watching “Life on the Line” I thought how much better they’d be handled—straight and clean and without fuss—in a 1930s or 40s working-man’s melodrama from Warner Brothers, maybe one by a director along the lines of Raoul Walsh. He made one of the great men-in-a-dangerous-profession pictures, 1940’s “They Drive By Night,” about truck drivers. But “Life on the Line” muddles them hopelessly, first by way of its myriad and busy structural devices, and then by inserting flashbacks that have all the logic of hiccups, and then, finally, by overplaying its melodramatic hand.

To John Travolta’s credit, he doesn’t phone in what could have been an indifferent role. His accent gets a little broad at times, but he’s sincere and conscientious in his portrayal of a working man who doesn’t want to be a hero, but will if he has to be. Sawa is better than okay too, as is Gil Bellows; only Bellefleur strays into egregious ham territory. The themes and the actors make you want the movie to be better, but the overreach combined with the sloppy sensationalism of the suspense scenes make “Life on the Line” the wrong kind of cinematic ordeal.