“Levity” is an earnest but hopeless attempt to tell a parable about a man’s search for redemption. By the end of his journey, we don’t care if he finds redemption, if only he finds wakefulness. He’s a whiny slug who talks like a victim of over-medication. I was reminded of the Bob and Ray routine about the Slow Talkers of America.

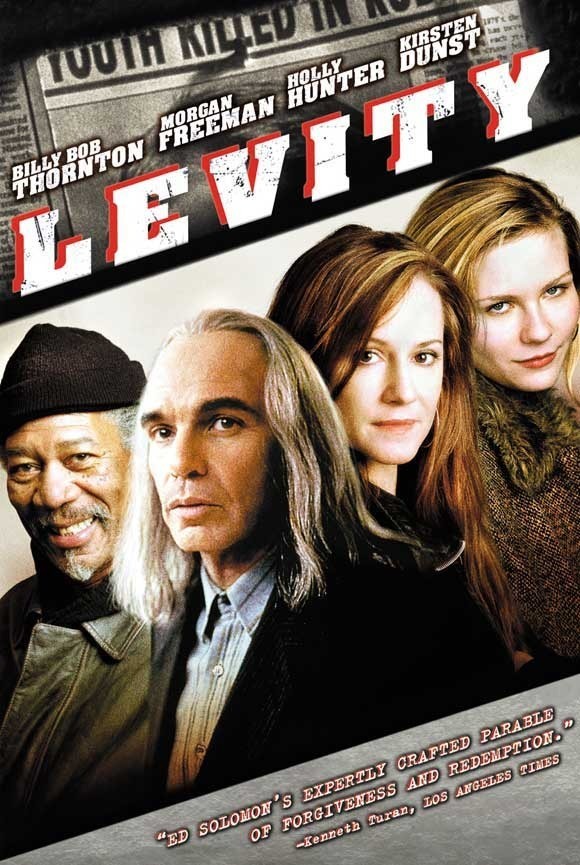

That this unfortunate creature is played by Billy Bob Thornton is evidence, I think, that we have to look beyond the actors in placing blame. His co-stars are Morgan Freeman, Holly Hunter and Kirsten Dunst. For a director to assemble such a cast and then maroon them in such a witless enterprise gives him more to redeem than his hero. The hero has merely killed a fictional character. Ed Solomon, who wrote and directed, has stolen two hours from the lives of everyone who sees the film, and weeks from the careers of these valuable actors.

The movie stars Thornton as Manuel Jordan, a man recently released from custody after serving 22 years of a sentence for murder. That his first name reminds us of Emmanuel and his surname echoes the Jordan River is not, I fear, an accident; he is a Christ figure, and Thornton has gotten into the spirit with long hair that looks copied from a bad holy card. The only twist is that instead of dying for our sins, the hero shot a young convenience store clerk–who died, I guess, for Manuel’s sins.

Now Manuel returns to the same district where the killing took place. This is one of those movie neighborhoods where all the characters live close to one another and meet whenever necessary. Manuel soon encounters Adele Easely (Hunter), the sister of the boy he killed. They become friendly and the possibility of romance looms, although he hesitates to confess his crime. She has a teenage son named Abner (Geoffrey Wigdor), named after her late brother.

In this district a preacher named Miles Evans (Freeman) runs a storefront youth center, is portrayed so unconvincingly that we suspect Solomon has never seen a store, a front, a youth, or a center. In this room, which looks ever so much like a stage set, an ill-assorted assembly of disadvantaged youths are arrayed about the room in such studied “casual” attitudes that we are reminded of extras told to keep their places. Preacher Evans intermittently harangues them with apocalyptic rantings, which they attend patiently. Into the center walks Sofia Mellinger (Dunst), a lost girl who is tempted by drugs and late-night raves, who wanders this neighborhood with curious impunity.

We know that sooner or later Manuel will have to inform Adele that he murdered her brother. But meanwhile the current Abner has fallen in with bad companions, and a silly grudge threatens to escalate into murder. This generates a scene of amazing coincidence, during which in a lonely alley late at night, all of the necessary characters coincidentally appear as they are needed, right on cue, for fraught action and dialogue that the actors must have studied for sad, painful hours, while keeping their thoughts to themselves.

Whether Manuel finds forgiveness, whether Sofia finds herself, whether Abner is saved, whether the preacher has a secret, whether Adele can forgive, whether Manuel finds a new mission in life and whether the youths ever tire of sermons, I will leave to your speculation. All I can observe is that there is not a moment of authentic observation in the film; the director has assembled his characters out of stock melodrama. A bad Victorian novelist would find nothing to surprise him here, and a good one nothing to interest him. When this film premiered to thunderous silence at Sundance 2003, Solomon said he had been working on the screenplay for 20 years. Not long enough.