Frances McDormand’s first film was “Blood Simple” (1984), but I really noticed her for the first time in “Mississippi Burning” (1988), standing in that doorway, talking to Gene Hackman, playing a battered redneck wife who had the courage to do the right thing. From that day to this I have been fascinated by whatever it is she does on the screen to create such sympathy with the audience.

Her Marge Gunderson in “Fargo” is one of the most likable characters in movie history. In almost all of her roles, McDormand embodies an immediate, present, physical, functioning, living, breathing person as well as any actor ever has, and she plays radically different roles as easily as she walks.

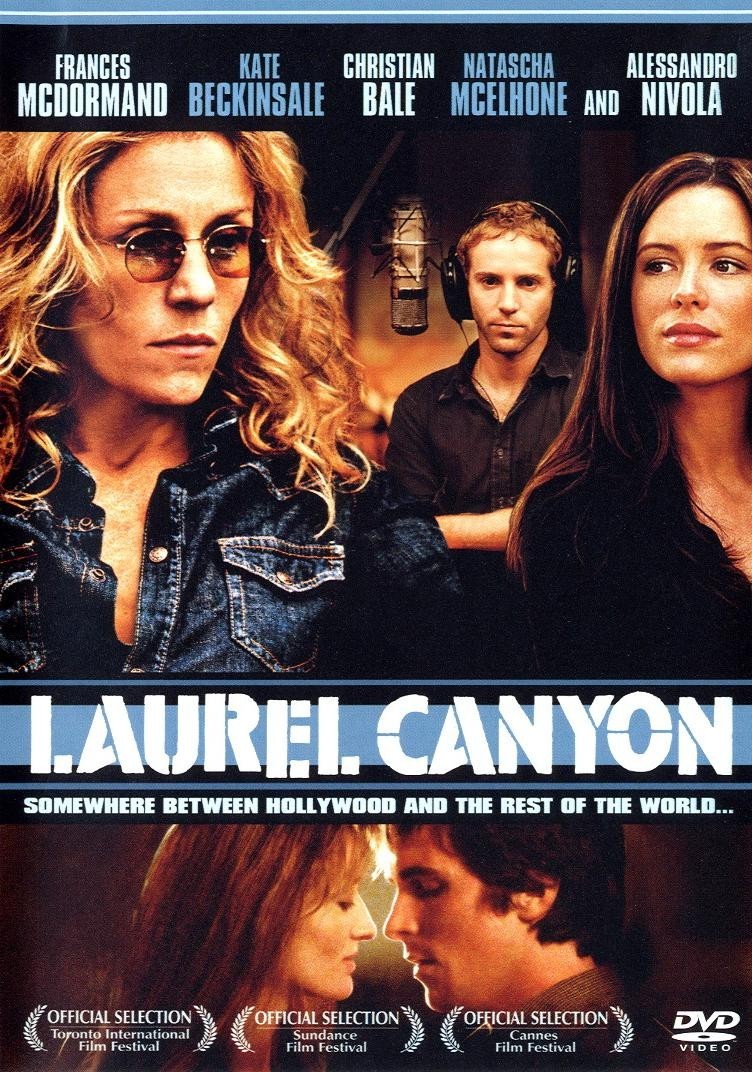

“Laurel Canyon” is not a successful movie–it’s too stilted and pre-programmed to come alive–but in the center of it McDormand occupies a place for her character and makes that place into a brilliant movie of its own. There is nothing wrong with who she is and what she does, although all around her actors are cracking up in strangely written roles.

She plays Jane, a woman in her 40s who has been a successful record producer for a long time–long enough to make enough money to own one house in the hills of Laurel Canyon and another one at the beach, which in terms of Los Angeles real estate prices means that when she goes to the Grammys a lot of people talk to her. A sexual free spirit from her early days, she is currently producing an album with a British rock singer named Ian (Alessandro Nivola) who is 20 years younger and her lover.

Jane has a son about Ian’s age, named Sam (Christian Bale), who is the product of an early and fleeting liaison. Sam is the opposite of his mother, fleeing hedonism for the rigors of Harvard Medical School, where he has found a fiancee named Alex (Kate Beckinsale). He studies psychiatry, she studies fruit flies, and true to their professions he will grow neurotic while she will buzz around seeing who lands on her.

Sam and Alex drive west; he’ll do his residency, she’ll continue her studies, and they’ll live in the Laurel Canyon house while Jane moves to the beach. Alas, Laurel Canyon is occupied by Jane–and Ian, and various members of the band–when they arrive, because Jane has given the beach place to an ex-husband who needed a place to live.

Significant closeups and furtive once-overs within the first few scenes make the rest of the movie fairly inevitable. Ian and Jane, whose relationship is so open you could drive a relationship through it, telepathically agree to include Alex in their embraces. Alex is intrigued by a freedom that she never experienced, shall we say, at Harvard Medical School, while Sam, meanwhile, meets the sensual Sara (Natascha McElhone), a colleague at the psychiatric hospital, and soon they are in one of those situations where he gives her a ride home and they get to talking so much that he has to turn the engine off. (That act–turning the key in the ignition–is the often-overlooked first step in most adulteries.) Sam and Alex are therefore on separate trajectories, and “Laurel Canyon” makes that so clear with intercutting that we uneasily begin to sense the presence of the screenplay. The movie doesn’t have the headlong inevitability of “High Art” (1998), by the same writer-director, Lisa Cholodenko. The earlier movie starred Radha Mitchell in a role similar to Alex, as a woman lured away from a safe relationship by the dark temptations of new friends. But “High Art” seemed to happen , and “Laurel Canyon” seems to unfold from an obligatory scenario.

Still, there is McDormand, whose character happens and does not unfold, and who is effortlessly convincing as a sexually alluring woman of a certain age. In fact, she’s a babe. Of the three principal female characters in the movie–played by McDormand, Beckinsale and McElhone–it’s McDormand who many wise males (and females) would choose. She promises playful carnal amusement while the others threaten long sad conversations about their needs.

How McDormand creates her characters I do not understand. This one is the opposite of the mother who worries about her rock-writer son in “Almost Famous.” She begins with a given–her physical presence–but even that seems to transmute through some actor’s sorcery. In this movie, she’s a babe; a seductive, experienced woman who trained in the 1970s and is still a hippie at heart. Now go to the Internet Movie Database and look at the photo that goes with her entry. Who does she look like? A high school teacher chaperoning at the prom. How she does it is a mystery, but she does, reinventing herself, role after role. “Laurel Canyon” is not a success, but McDormand is ascendant.