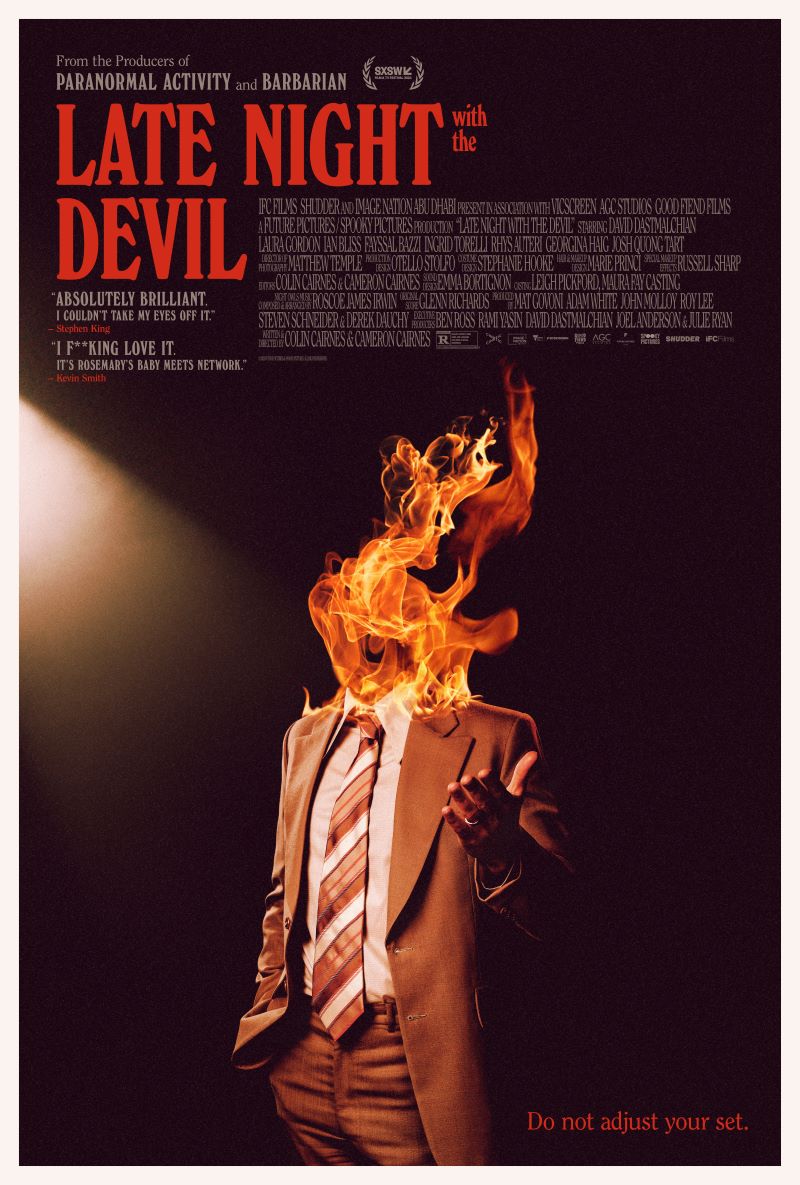

Is there any scenario in which “Late Night with the Devil” could have delivered on its promise? I’m not seeing it. Set in 1977, the movie envisions a nonexistent fourth commercial broadcast network (there were only three back then) and then imagines a competitor emerging to take down the reigning king of late night talk shows in the ’70s, Johnny Carson. The rival is Jack Delroy (David Dastmalchian), a local Chicago talk show host who was bumped up to the national level. This backstory and more is explained in a five-minute prologue that includes one key biographical fact I’ll skip here, because once you hear it, you can see the ending coming from 81 minutes away. Suffice to say that Jack’s been on the air for six seasons and his ratings have never beaten Carson’s, though he came close once.

Then comes sweeps week, a quarterly event wherein the AC Nielsen ratings company determines what networks can charge for airtime, and the networks try to gin up the numbers by airing their biggest, splashiest, most outrageous stuff. Jack and his oily producer Leo (Josh Quong Tart), who could be the brother of Sean Penn’s coke fiend lawyer in “Carlito's Way,” have for years been doing supernaturally-themed Halloween broadcasts with a costume contest. They decide to kick things up a notch by inviting a package of thematically interlinked guests.

One is a psychic known as Christou (Fayssal Bazzi) who does a mentalist routine, guessing factoids about the audience in what seems like a pretty scammy way. Another is Carmichael the Conjurer (Ian Bliss), an Amazing Randi “debunker” type who quickly explains how Christou might have fooled the audience into thinking he had paranormal abilities. Then comes the evening’s centerpiece: bestselling parapsychologist Dr. June Ross-Mitchell (Laura Gordon) interviews Lilly (Ingrid Torelli), the only survivor of a satanic cult’s mass suicide during a standoff with police. Things get wilder, weirder, and more disgusting from there, and there’s no denying that Australian filmmakers Colin and Cameron Cairnes and their talented crew put their backs into the production, particularly the gooey practical effects.

But the movie gets in its own way and trips over itself repeatedly. The from-the-jump insistence that it’s a “found footage” movie built around a buried broadcast instantly creates unrealistic expectations for everything that follows. This is a movie that pretty much does whatever it wants whenever it wants to, and doesn’t feel too much pressure to stay beholden to the visual conventions of circa-1977 American late night talk shows that can be researched and emulated pretty easily thanks to YouTube. (To be fair, though, I’ve seen very few “found footage” movies that actually feel like footage that was found. Almost all of them cheat so often that you have to wonder why anyone wants to make them in the first place.)

The prologue also strikes me as a mistake because it frames the rest of the movie as a thing that you have to get through in order to arrive at the ending you already know is coming based on the prologue, whereas simply presenting the broadcast itself without explanation or a framing device, as an artifact, would have thrown audiences into the deep end of the pool and created a sense of mystery throughout, while all the important plot points were being communicated organically, within the context of the broadcast (people talk to Jack on the air about what’s happened in the years leading up to this disaster, and it’s very well done; it sounds like what people on a TV show would actually say to somebody in his situation). There are also some “backstage” moments, seemingly shot on the fly by the network cameramen onstage, that invite the question of why not one but two cameramen decided to go documentary rogue on this event, and how the footage ended up being edited together with the bits that were originally intended for broadcast. Did somebody cut it all together in the style of a dramatic feature film, then hide that master tape in the “CURSED OBJECT/DO NOT OPEN” vault?

The found footage stylistic tics and other signifiers of “realism” raise the question of why anybody in the studio audience stuck around after one of the guests projectile-vomited what looks like the sentient black goo from the “Venom” movies. Yes, it’s true, Hitchcock derided people like me as “The Plausibles,” but even Hitch knew that a movie full of holes had to be cooking to make people turn off their nitpicker brains, and this one rarely rises above a simmer.

Dastmalchian is quite good as Jack, especially in moments of vulnerability and self-delusion, but I don’t quite see the starmaking performance here that some of my colleagues have noted, mainly because I didn’t find him plausible as a guy who rose to national prominence on the late night talk show circuit on the basis of being hilarious. He reads monologue jokes and desk banter that’s supposed to be hilarious, and we hear the audience roaring, but that’s the movie telling you that he’s funny, which isn’t the same thing as him actually being funny; the audience laughed at Robert DeNiro’s jokes in “Joker,” too, and for all his chameleonic acting genius, DeNiro was about as funny as a potato in that role. Which is another way of saying that the performance succeeds as drama but doesn’t work in a way that sells the core idea that somebody believed in this guy as a young Turk who could unseat Johnny Carson.

Still, there’s no questioning the originality of the idea and the vibe, whether you think the film pulls it all off in totality. I would happily pore over a large-format coffee-table book of freeze-frames from this movie. It’s richly imagined, and you can tell everyone had fun immersing themselves in this strange and often disturbing world. It doesn’t quite look like 1977, especially the unfortunate use of AI-generated interstitial and background art, which pretty much screams “tech bro fads of the 21st Century.” (What, they couldn’t have hired one of their starving graphic artist friends for the cost of a few vintage wide-lapeled shirts?) But the movie for-sure says “the ’70s” in a general way, particularly cinematographer Matthew Temple’s lighting (though some of the camera moves are distractingly post-“Goodfellas” Scorsese); the “Sunday afternoon at TGI Friday’s” clothes on the audience members (by costumer Steph Hooke); and the typeface used for the show’s credits (the production designer is Otello Stolfo).

And there’s a grimy, acquisitive aura embalming the whole thing that I vividly recall from my own ’70s childhood, sitting on my parents’ living room rug watching sweaty people with shaggy hair chain-smoking on talk programs, reporters going “undercover” in brothels and shooting galleries on local newscasts, and contestants throwing gross innuendos at each other on game shows. You can imagine Satan looking at TV in the ’70s and calling his agent.