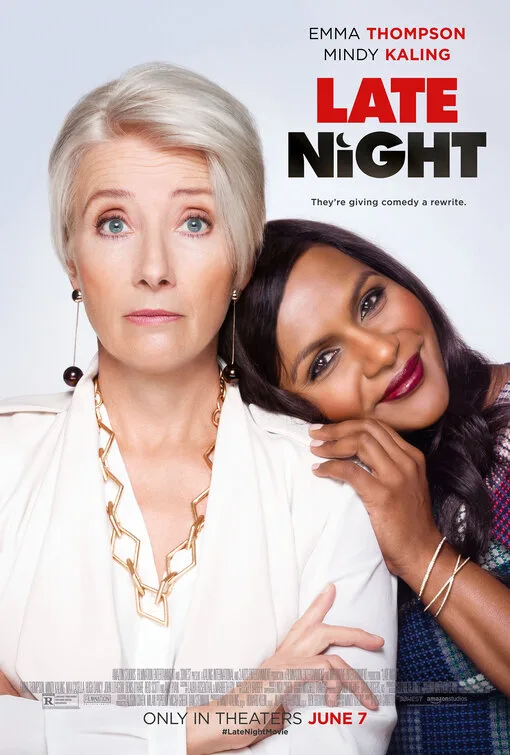

At a crucial moment in “Late Night,” written and co-produced by Mindy Kaling, who also stars, Kaling’s Molly Patel – a new hire to the writing staff of Katherine Newbury’s late-night talk show – accuses Katherine (Emma Thompson) of viewing her as a “diversity hire.” Katherine’s response is swift and blunt: “You are a diversity hire. But the point is you’re here.” And now that Molly is in “the room where it happens,” how will she stay in the room?

Comedians often talk about “tough crowds,” audiences who are begrudging with their laughter. Well, comedians are the toughest crowd of all. “Late Night,” directed by Nisha Ganatra (whose television credits are lengthy, including Kaling’s The Mindy Project) is a feel-good movie – in the best sense – with subversive commentary woven into it, so subtly at times you might miss some of it. “Late Night” has a lot to say, not just about “diversity” as represented by Kaling walking into a writer’s room of all white males, but also diversity in terms of class, gender, and age. Kaling was first hired as a writer on NBC’s “The Office” through a diversity initiative, after getting a lot of attention for “Matt & Ben,” the off-Broadway play she co-wrote with Brenda Withers, where Kaling played – hilariously – Ben Affleck. “Late Night” comes directly from Kaling’s own experiences. This is an earnest and funny comedy, with very sharp teeth.

Late-night TV is, notoriously, male-dominated, but in “Late Night” Kaling imagines a world where the King of Late Night is actually a Queen. (This choice has real satirical bite.) Newbury has been hosting Tonight for 30 years. Her office is lined with her Emmy Awards. She has refused to compromise her standards (as she sees it), and has rejected social media, memes, viral videos, etc. She’s British, so accusations of her being an “elitist” don’t bother her in the slightest. But her ratings going into a nosedive … that does bother her. Katherine’s writing staff is made up of men. She has never gotten to know them, and many of them have never even met her. The president of the network (Amy Ryan) wants to replace Katherine with a Dane-Cook-type (Ike Barinholtz), whose “provocative” routines might give the show some juice. In a panic, Katherine – known for not liking women – orders her right-hand man Brad (Denis O’Hare) to hire a woman, stat. It’s the most brazen “tokenism” you can imagine. Molly Patel just happens to be interviewing with Brad on that very same day. She has no experience, but you can see Brad considering the optics, ticking off the boxes: she’s a woman, and she’s a woman of color. She’s hired.

When Molly walks into that writer’s room, nobody wants her there. There isn’t even a chair for her, and she has to sit on an overturned trash can. Reid Scott plays Tom, who keeps reminding everyone that he writes Katherine’s monologues. Tom is a “legacy hire,” and yet he feels superior to Molly’s status as a “diversity hire.” In his mind, it’s different. The only guy who is somewhat open to Molly is Charlie (Hugh Dancy), but turns out he’s a Ladies Man, he’s got conquest on his mind. Kaling has made some interesting choices in how she has positioned Molly. Molly is not out there working comedy clubs, performing with improv groups, engaged in the hustle. Before getting the writing job, Molly worked Quality Control in a “chemical plant” (she corrects people who call it a “factory”), entertaining the workers on the floor with an ongoing “comedy routine” over the loudspeaker. She is truly an outsider. This gives Kaling a lot of room, since Molly is naive enough to be starry-eyed about the opportunity she’s been given. She doesn’t know any better. She shows up for her first day of work bearing cupcakes. One of her mantras is Yeats’ Cloths of Heaven, which she chants as she walks towards the office:

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

Molly brings her Quality Control experience to bear, suggesting ways to make the show better (ingratiating herself with no one). Kaling knows this territory very well, the lack of diversity in writers’ rooms, plus the overall boys’ club mentality of comedy in general. The pioneering Joan Rivers talked and wrote about it for years. (Rivers remembered being onstage at Second City in the middle of a group improv, and when she stepped into a scene in progress, all the guys held out their arms at her, like, “Stay back. We don’t want you in this scene.”) Despite the toxicity of much of this, Kaling’s approach is light-hearted, and she’s got a great sense of the absurd. There are no villains. Even the guys who clearly don’t want her there are just beneficiaries of a system set up long before they came around. Amy Ryan’s character at first seems like a witch on high heels, but she’s not <i>wrong</i> about Katherine being out of touch and arrogant. Something has got to change.

This is some of Emma Thompson’s best work (and that’s saying something). There’s a truly subversive sequence where Newbury gets embroiled in her own #MeToo moment, calling into question many assumptions about men, women, and power. What’s subversive about it is how it shows the complexities behind the scenes, the pain, the human frailty, but how does one even address these complexities in such a savage “off with her head” atmosphere? Kaling addresses it. It’s very bold. Katherine’s husband (John Lithgow) is kindly and indulgent, and suffering from a debilitating disease. There’s always more going on than meets the eye. As Molly gets sucked into the rhythms of her job, it gives Kaling an opportunity to critique how things work, but also – in some of the smartest sequences – examine why jokes work, what makes a joke go viral, the subtleties of comedy itself.

On one level, “Late Night” has no surprises. Everything happens as you would expect, and right on schedule. But on a deeper satirical level, the level where the movie really works, it’s one surprise after another. Watch how Molly’s “romance” with Charlie is handled. A more conventional movie would have prioritized it in a much different way, giving it more weight than it deserves. Charlie is beautifully in proportion. The movie is not about him. Watch how the dynamic between Molly and Tom develops. It happens almost via stealth, and so the payoff – when it comes – is much more satisfying than it might be otherwise. And mostly, the relationship between Molly and Katherine, growing in fits and starts in scene after scene with Kaling and Thompson – shows two women, struggling to find a handhold in a culture that doesn’t want them, struggling – at first separately, and then together, to stay “in the room where it happens.”

At Indie Memphis last year, Senior Programmer (and now Artistic Director) Miriam Bale made a speech where she spoke about why the festival was so unique, what made it so special. Bale said, memorably, “When there’s enough diversity, you don’t have to worry about diversity. You can focus on art!” In its own way, “Late Night” shows how that process can occur. It’s not easy. You may have to sit on a couple of overturned trash cans in the process. But everybody benefits when more voices are heard.