This is inevitable: Painful social conflict will arise between those Chinese citizens who produce consumer goods for the world, and those Chinese who want to consume them. “Last Train Home,” an extraordinary documentary, watches that conflict play out over a period of three years in one family. It’s one of those extraordinary films, like “Hoop Dreams,” that tells a story the makers could not possibly have anticipated in advance. It works like stunning, grieving fiction.

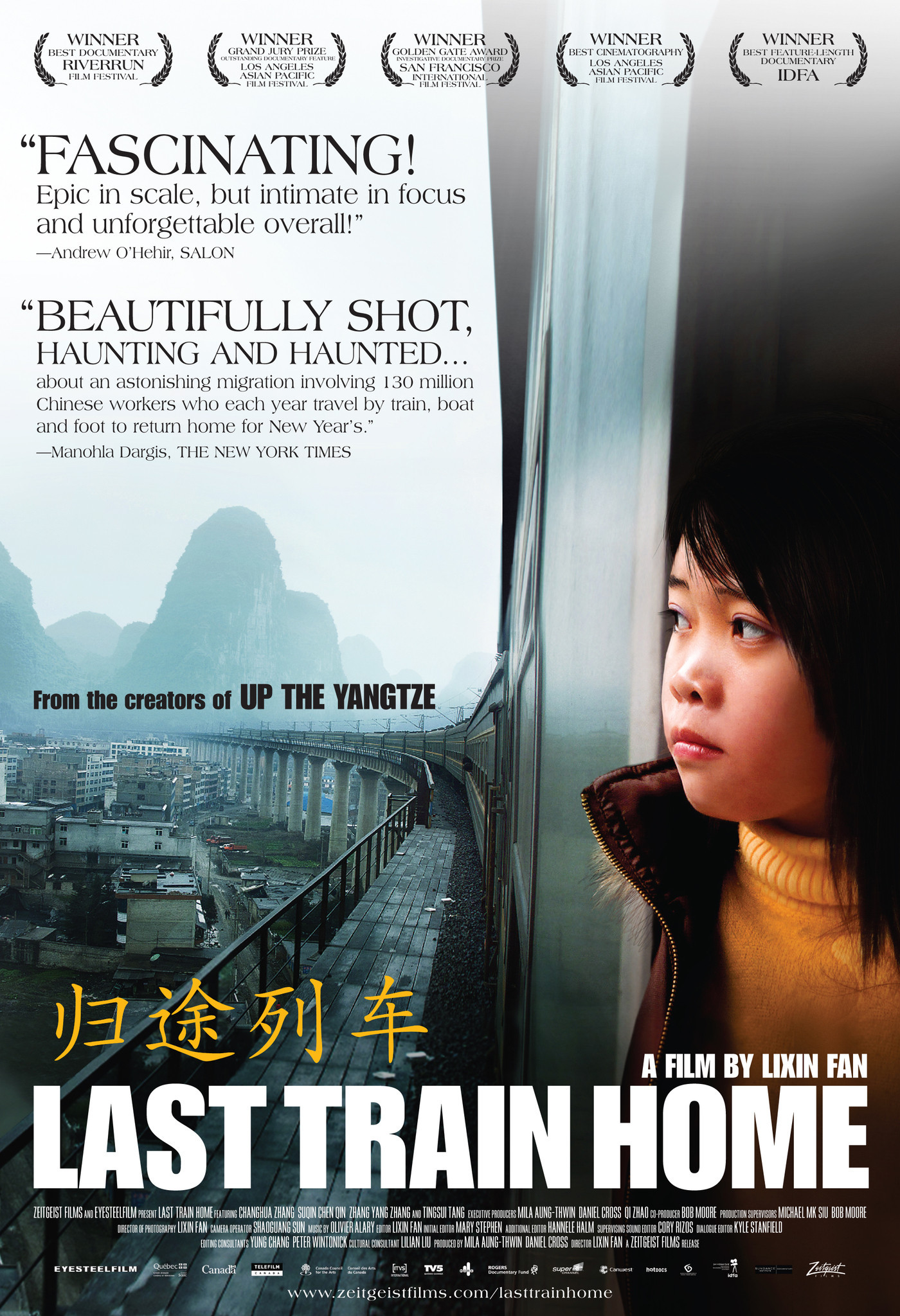

The film opens like a big-picture documentary, showing us a huge crowd being directed by police as it grinds its way forward. We are informed that these are some of the 130 million Chinese citizens who make an annual train journey from urban centers to their provincial villages — “the largest human migration in the world.” Umbrellas of every description protect them. They carry enormous bundles — gifts, perhaps, or food for the journey. They’re headed home for the Chinese New Year.

We gradually center on Zhang Changhua and Chen Suqin, a married couple. Years ago, they left their home in the Szechuan province to take low-paying jobs in a textile factory in Guangzhou, which is the huge industrial city on the mainland next to Hong Kong. Here, in row after row, they work bent over sewing machines, assembling perhaps the jeans I’m wearing right now. They live in dormitories — married adults, with next to no privacy.

They save every yuan they can to send home. They left their children behind to be raised by a grandmother. Their dream is that by 15 years of this toil, they will pay for the children to finish school and live better lives. For that dream, they have sacrificed the life of parenthood, and are like strangers at home to children who know them as voices on the telephone, seen on the annual visit.

This is a reality Dickens could hardly have imagined. The fruit of their toil has contributed to China’s emergence as a global economic power. But their lives are a grim contrast to the glittering Beijing of the Olympics, the towers of Shanghai, the affluent new business class. And here is the part you may sense coming: Are their children grateful for what amounts to the sacrifice of two lifetimes?

The filmmaker, Lixin Fan, follows this family for three years, in the city and in the village. We hear much about how Chinese parents pressure their children to study hard and excel. Overseas, they frequently do succeed. But China is a huge nation, so large that a generation may not be long enough to rise from poverty.

Their daughter, Zhang Qin, is in high school, and comes to regard her parents as distant strangers — and nags. She’s had enough of it. But what she does is beyond heartbreaking. She moves to Guangzhou and gets a factory job. She does the math. If she keeps her wages instead of sending them home, she’ll have them to spend on herself. Does it occur to her to suggest her parents move back home with her brother, while she helps support and repay them? Not a chance.

There is so much to say about this great film. You sense the dedication of Lixin Fan and his team. (He did much of the cinematography and editing himself.) You see once again the alchemy by which a constantly present camera eventually becomes almost unnoticed, as people live their lives before it. You know the generations almost better than they know themselves, because the camera can be in two places and they are usually in one or the other.

There is a quiet moment in a mall. On their day off, Zhang Qin and her friends go shopping. They like a pair of jeans: “Are these made in our factory?” No, in another. Of course they want them. Of course their generation wants them. But their generation doesn’t want to work years leaning over a sewing machine and sleeping in a dorm.

We read about the suicides in Apple’s plants in China. Seeing this film, you suspect there are many suicides among workers in factories whose brands are less famous than Apple. Chinese peasants no longer live without television and a vision of another world. They no longer live in a country without consumer luxuries. “Last Train Home” suggests that the times they are a-changin’. The rulers of China may someday regret that they distributed the works of Marx so generously.