Since late 2012, the Syrian Civil Defence, a volunteer organization also known as the White Helmets, have been rescuing civilians underneath rubble from barrel bomb attacks, courtesy of President Bashar al-Assad’s Air Force and later the Russian Air Force. They’re often the first on the scene and most of their activity consists of urban search and rescue. Sometimes they find people alive, often gruesomely injured. Other times they’re retrieving the dead. Many of those found are infants and children. The White Helmets are heroes, in every sense of the word.

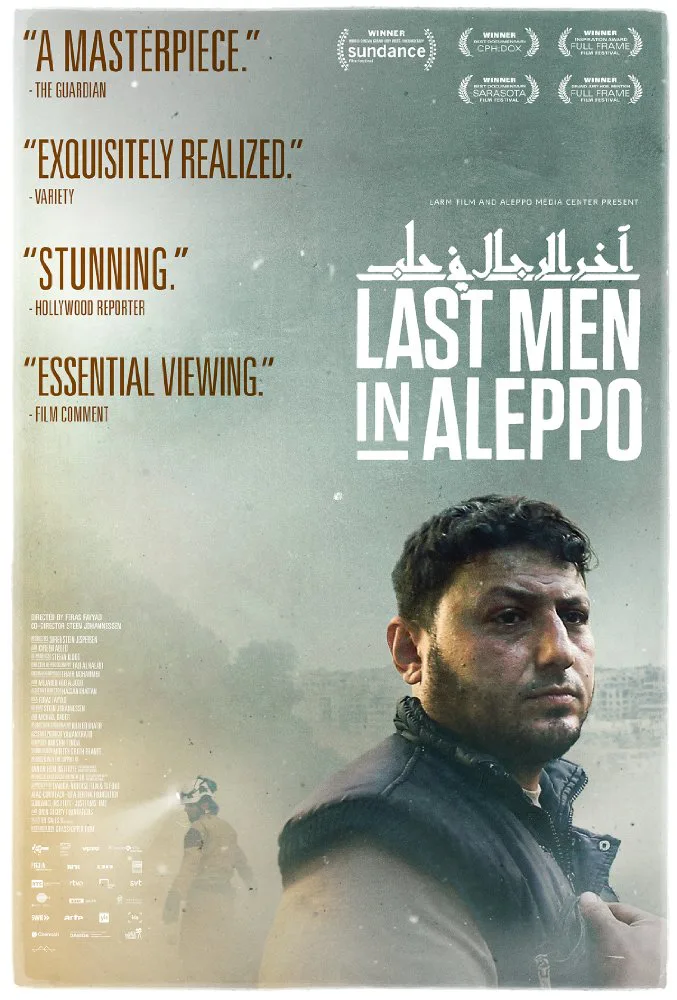

Yet, Firas Fayyad’s “Last Men in Aleppo,” a vérité portrait of the White Helmets filmed between 2015 and 2016, never operates as a sentimental tribute to these brave men, extolling their virtues to mawkish proportions. Instead, it’s an unflinching depiction of life in a vulnerable city, a place where innocents are constantly under attack, and the few people doing their best to protect it. Fayyad eschews extraneous exposition from the film, never focusing on the various nuanced political reasons underlying the Civil War. Fayyad just follows the White Helmets on the job and the few quiet moments in between, doing his best to shed light on a dark part of the world.

“Last Men in Aleppo” primarily films two men in one unit: Khaled, a boisterous family man who was nicknamed “the hero of Aleppo” after video of him saving a baby trapped in a building spread around the world in 2014; and Mahmoud, a quiet man uncomfortable with any displays of heroism but propelled by a sense of duty. Both of these men, like the rest of the White Helmets, held regular jobs before the Civil War; Khaled was a painter and decorator while Mahmoud was a student. Fayyad emphasizes that these are normal men acting in extraordinary circumstances because they view their lives as a sacrifice for others. “This is our destiny,” Khaled says. “We’re going to die like everyone else.”

Fayyad immerses the audience in the world of the White Helmets almost immediately. As they walk the city, they constantly survey the skies for sounds of helicopters, which indicate imminent bomb attack. After they hear of an attack, they rush over to the wreckage where they search for bodies. They’re plagued by insufficient resources and near constant obstacles—a car overheats on the way to a site, too few body bags for the dead, and dwindling numbers among their ranks. When they’re off the clock, so to speak, they crack jokes and complete personal projects, like a makeshift pond. Khaled plays with his kids while wrestling over whether to send them to the Turkish border just so they can be safe. “I’d rather they die before my eyes than have something happen to them far away,” he eventually tells a comrade, with the full weight of that statement palpable in his voice.

Fayyad, co-director Steen Johannessen, and director of photography Fadi Al Halabi document various rescue missions and firefights at obviously great risk to themselves, illustrating the horrors of the job without once fetishizing them. Make no mistake: “Last Men in Aleppo” can be a very difficult watch. Though Fayyad breaks up the brutality with scenes that illustrate humanity in Aleppo, especially one where Syrian parents take their children to a playground during a supposed ceasefire, the images of grotesque violence largely against children are necessarily present throughout. Fayyad doesn’t ignore the antecedents to the violence—he films protests against Bashar and civilians affected by the bombing routinely denounce his name—but the power of the imagery primarily derives from the questions he chooses not to answer. Why did this happen? How can people in power have such disrespect for human life? When will it end? The horror of “Last Men in Aleppo” lingers long after the film concludes partially because Fayyad prompts the audience to answer those questions themselves.

However, not all of Fayyad’s choices are as sound as that one. Though “Last Men in Aleppo” thankfully doesn’t feature a manufactured narrative arc, its shapelessness can occasionally be a liability since it rarely breaks from a predictable, repetitive rhythm that grows somewhat tiresome by the end. More than that, Fayyad includes one too many conversational scenes that seem to needlessly “explain” the conflict and its effects solely for the audience’s benefit. The conversations themselves don’t feel artificial, but they do stand in stark contrast to the understated nature of the rest of the film, which hardly goes out of its way to keep viewers on steady ground.

While “Last Men in Aleppo” doesn’t offer much in the way of hope or optimism (even the quiet scenes are beset by persistent dread), the White Helmets’ collective insistence that they’ll never abandon Aleppo stands as an overwhelming testament to their actions. These are men that have largely accepted that they will die at the hands of a bomb, but they refuse to flee for the border. Fayyad stresses that Aleppo will always be their home, and as long as it’s under siege, people like Khaled and Mahmoud will be there to protect it. “Show me a hero and I’ll write you a tragedy,” said Fitzgerald over 70 years ago. “Last Men in Aleppo” understands the gravity of that line to a T.