Inspired, disquietingly enough, by an urban legend, “Kumiko The Treasure Hunter” does not wear the outlandishness of its premise on its sleeve. Rather, this new film from the Zellner brothers—writer Nathan and co-writer and director David, both of whom also act—plays out as a deliberate, somber character study that semi-eerily morphs into comedy of middle-American manners and then into something else again.

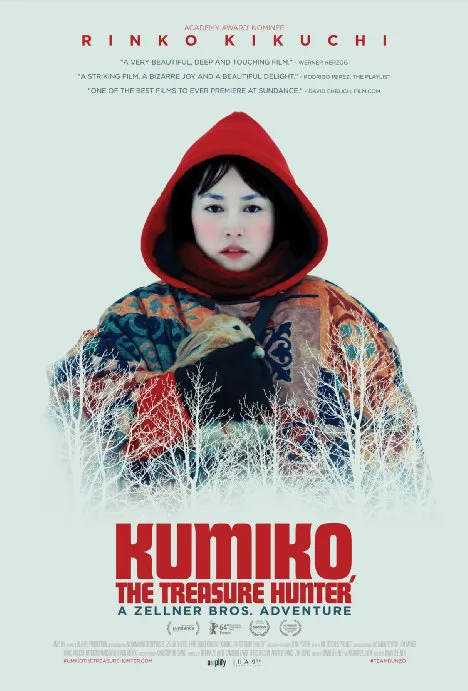

The title of the movie seems to promise adventure, and the movie does deliver that, though not in the conventional manner. Despite an opening sequence in which a VHS cassette tape is unearthed in an exotic context, Kumiko, portrayed in a startlingly sustained performance by Rinko Kikuchi (“Babel,” “Pacific Rim”) is a not-so-young-anymore woman in today’s Tokyo whose imaginative life is far more vivid than her day-to-day reality. “I am like a Spanish conquistador,” she explains at one point to a curious library security guard. You’d never know given her day to day routine, which involves making weak tea for a boss too lazy to fire her (at least for a while), ineffectually feeding her pet rabbit Bunzo, and watching and re-watching a videocassette of the Coen brothers’ classic film “Fargo.” Kumiko, fixating on the opening title text that pegs the movie as “a true story,” is convinced that the suitcase full of money buried by one of that film’s characters is at the Minnesota-North Dakota border for the taking of anyone intrepid enough to seek it.

In the movie’s opening forty minutes or so, the filmmakers use relatively conventional means to convey the sadness of Kumiko’s depressive state and directionless life. A perfunctory dressing-down from a boss, an on-the-street encounter with an all-too-perky friend from a prior time in Kumiko’s life, a hectoring phone call from Kumiko’s mom. A series of life-fractures—including an awkward and eventually mordantly funny breakup with the aforementioned rabbit—set Kumiko on a course to the U.S.A., where relatively conventional ideas of quirkiness are applied to the various American characters, beginning right off the bat at a Minnesota airport, where Kumiko, who barely speaks English, is waylaid by an odd couple of “tourist consultants” (Nathan Zellner and Brad Prather) who are also religious proselytizers. As she sets off into the freezing weather—conditions that make the movie “Fargo” itself look more like “To Catch A Thief”—Kumiko runs into a host of other Lonely People, including an older woman who tries to interest her in James Clavell’s “Shogun,” a bus driver who apologizes that his Carpal Tunnel Syndrome makes it impossible for him to change a bus flat, and a friendly cop (David Zellner) who tries to convince her that “Fargo” is indeed just a movie, even as he contemplates the remote possibility of initiating some kind of romance with her.

The movie tries to compensate a bit for the familiarity of these characters by showing real patience in presenting them—the strategy being to show the poignancy behind the oddness. The results are mixed; I think any viewer who doesn’t hook into this movie’s worldview right off the bat is going to find the going glacial rather than compassionately exploratory. Also potentially alienating is the movie’s turn into Lynchian territory for the film’s finale. It doesn’t come off as cruel, precisely, but there’s at the very least a sense of evasion at work. In the plus column, the movie is beautifully composed and shot, with a lot of smartly evocative images (I was particularly taken by the rendering of a plane’s de-icing as a kind of freezing hellscape). And finally, Kikuchi’s performance, which is a marvel of concentration and craft. As beautiful as ever, she’s nonetheless drained her gaze of any suggestion of coquettishness, investing her character with a haunted quality that, as the saying goes, howls in the bones of her face.