There’s a scene in “Grand Canyon,” a film released shortly before “Juice,” that’s like a setup for the second movie’s whole tragic story. In the earlier film, an older black man confronts a group of young punks on the street. One punk has a gun. He asks the older man, “Do you respect me, or do you respect my gun?” The answer is: “You don’t have that gun, there’s no way we’re having this conversation.” That is a dangerous answer, but an honest one, and “Juice” is like a mirror image of the “Grand Canyon” scene; it tells the story of the young men – how they got into a criminal situation, and how they got the gun. It tells one of those stories with the quality of a nightmare, in which foolish young men try to out-macho one another until they get trapped in a violent situation which will forever alter their lives.

The movie was directed and co-written by Ernest Dickerson, the cinematographer on Spike Lee’s films, and like Lee’s “Do the Right Thing” it is filled with details of the daily life, fashions, music and language of a black neighborhood. It introduces its four central characters as they get up in the morning and venture out from poor but supportive homes into New York streets where, as they perceive it, the person with a gun commands respect. At first the movie seems meandering, following these young men through their daily routines, listening to their talk, looking at the street life in their neighborhood, watching the ambition of one nicknamed Q (Omar Epps), who dreams of being a disc jockey in a club.

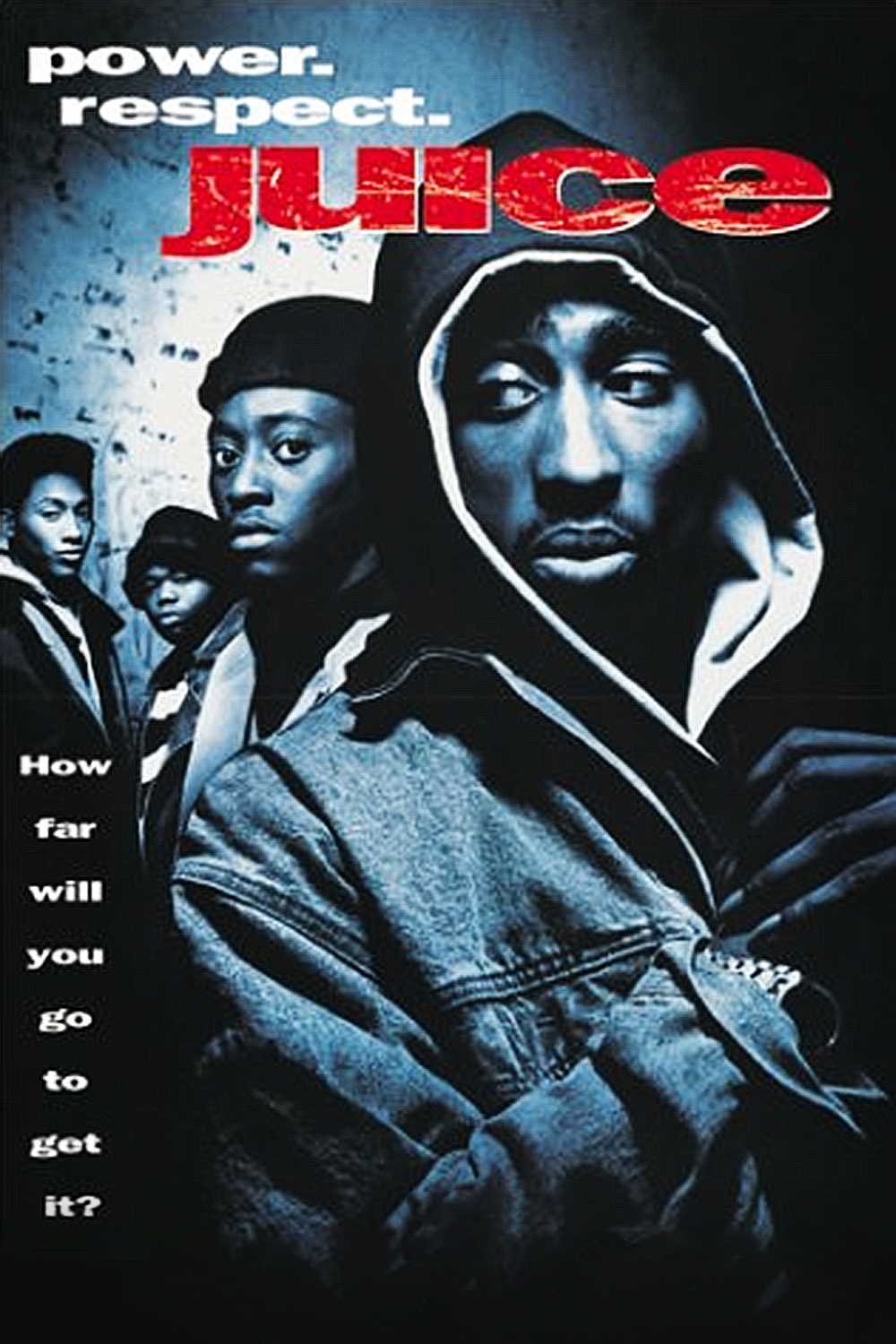

Then the focus tightens, as everything turns wrong, when Bishop (Tupac Shakur) gets his hands on a gun and decides the four of them should stick up the corner store. There is a sense in which the existence of the gun leads to the necessity of using it; without the cheap handgun, there would be no crime, and lives would be saved. Q doesn’t want anything to do with the stickup; his mind is focused on a DJ contest at a local club. But Bishop has the stronger personality, and badgers them all into coming along.

The best shot in the movie takes place in a club where Q has just done a successful gig as a DJ, and is filled with joy, until he sees the unsmiling faces of his friends in the crowd, and realizes he has to leave, now, and commit the stickup. What happens next depends too much on surprise for me to reveal it, but the movie generates a real tension in its closing passages, as it shows its characters trapped in a plot that seems to be unfolding according to its own merciless logic.

Much of the strength of the film comes from the actors, Epps, Shakur, Khalil Kain as Raheem, whose enthusiasm for the stickup ends tragically, and Jermaine Hopkins as Steel, a pudgy innocent.

They are able to make us know their characters, which is important if “Juice” is to be more than just a morality play. It is also interesting the way Dickerson’s story makes them – and the street culture of cheap handguns – the instruments of their own downfall.

There are a lot of cops in the movie, but for a change they are seen not as villains but as street troops in the fight against crime.

It’s a common criticism of cinematographers that when they direct their own films, they pay too much attention to style, not enough to the story. The scene-setting opening moments of “Juice” seem almost too picturesque, but then we feel the underlying logic of the story, and Dickerson finds a rhythm that uses the visuals instead of just flaunting them. “Juice,” like “Boyz N the Hood” and “Straight Out of Brooklyn,” is like a reaction to years of movies that have glamorized urban violence. There is a real terror in the faces of these kids as they realize that people have died, that guns kill, that your life can be ruined, or over, in an instant.