For many people, Judy Garland’s story is the story of Hollywood: a natural talent who grew up in front of the movie camera, the pressures of fame that consumed her and the tragedy she eventually met. She comes to mind anytime we lose a star too early, whenever we reference “The Wizard of Oz,” or when we hear her golden voice on the radio over the holidays. Naturally, she’s a figure whose story still has the power to fascinate many, and in Rupert Goold’s new biopic “Judy,” we revisit the last few months of her time on earth with us: the booing crowds, the empty bank accounts, and the custody battle to come. It’s less the portrait of the glamorous Judy Garland we’ve put on a pedestal, forever young and singing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” or “The Trolley Song,” and more the wounded figure still unsure if she could perform again the next night.

Adapted by Tom Edge from Peter Quilter’s play, Goold’s “Judy” finds its star struggling to stay afloat in Los Angeles and London. Although she gives her everything on stage, behind-the-scenes, she’s broke and in desperate need of another break. She leaves her two younger children, Lorna and Joe, in the care of their father Sidney (Rufus Sewell) and embarks on yer another redemption tour in England that would help revitalize both her reputation and her fortunes. Unfortunately, no one understands the trauma Judy endured in her childhood years, and many of her present-day handlers and casual observers write her off as merely a has-been diva. If only they knew what the audience could see in the movie’s flashbacks to Judy’s tortured past.

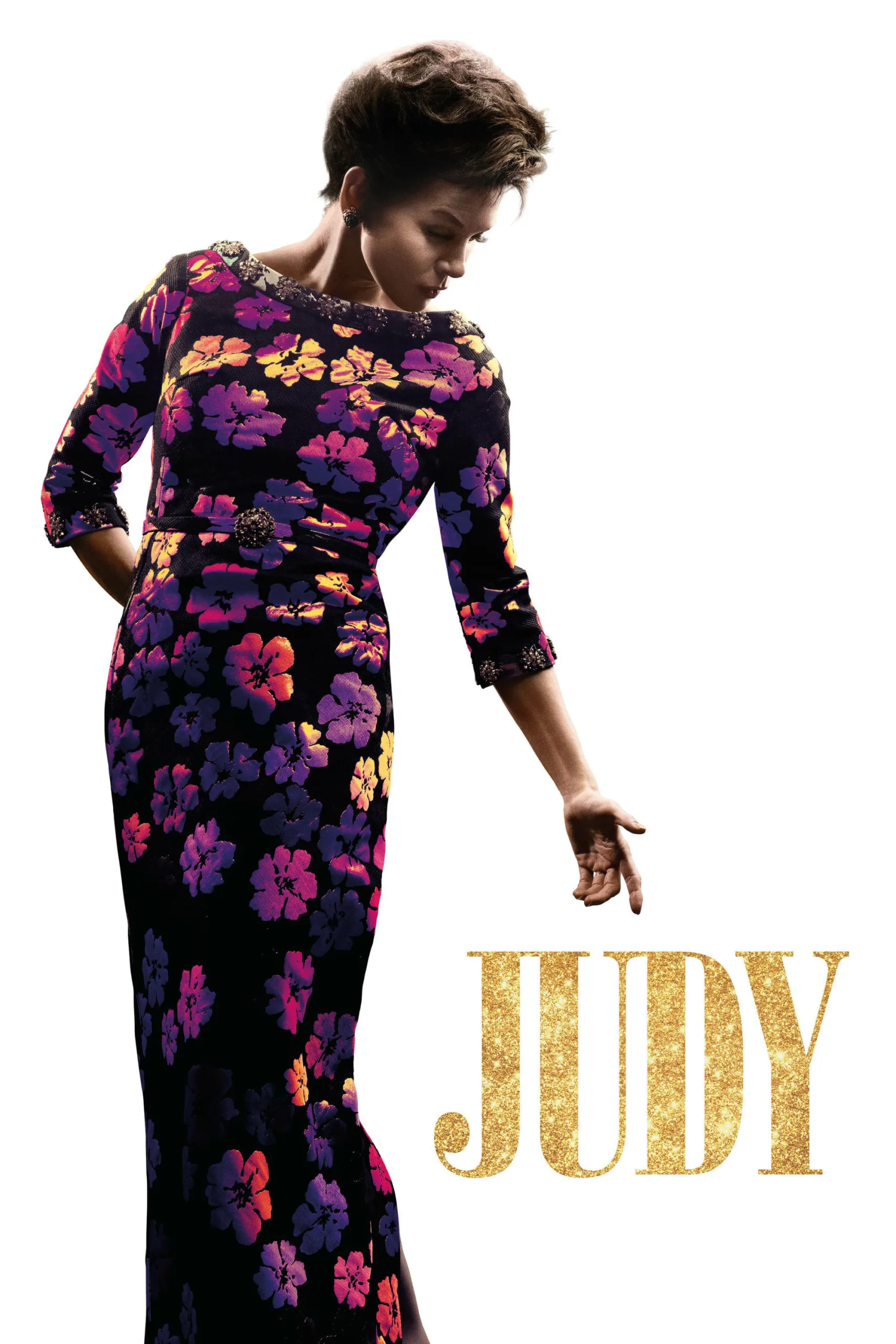

As played by Renée Zellweger, this Judy is painfully and visibly anxious. Or, perhaps this is her idea of drug-induced twitching. Either way, there are spots in the movie where Zellweger’s affected manners become too distracting and overshadow everything else around her. These tweaks and fidgets may be so noticeable because the team behind the film might have hoped to chase that “A Star is Born” awards luster, or court groups with a penchant for rewarding mediocre biopics. Try as she might, Zellweger’s Judy never goes beyond an impression of the multi-talented artist; her all-caps version of acting fails to allow the role to feel natural. In trying so hard, Zellweger defeats herself. The audience is meant to feel and see every muscle in her strained back and flailing arms while performing, but watching the actress work is not why most of us would buy a ticket to “Judy.”

For purists and die-hard fans, “Judy” might smack of heresy. Of course, it’s not altogether factual—there’s entertainment to be made. Better to punch up the details for some dramatic tension than to play it out like a dusty made-for-TV documentary. But even the show-stopping numbers with Garland’s hits fail to strike the right tone. Goold manhandles these scenes with poor directing, barely masking Zellweger’s noticeable lip syncing. Some of the shots during the performances are unforgivably atrocious, cutting Judy’s face out of frame so that she holds less than a third of the screen and the empty air hogs the rest. It feels like an artless attempt to seem deep. The script also includes a subplot in which Garland is rescued by two “friends of Judy” that feels more contrived than a well-meaning tribute.

Although “Judy” is not without its stumbling blocks, it does surprisingly well at contextualizing Garland’s abusive childhood. The audience watches uncomfortably as young Judy (Darci Shaw) is forced on and off pills with enough regularity to warrant a call to child services. We also learn how she was shamed for wanting to eat burgers and play like other kids, and about the latent creepiness and control MGM mogul Louis B. Mayer held over her early years. It was enough unhappiness to last many lifetimes, but for Garland, it was enough to cut hers short. Although the fascination with her twilight days may only feed the mythology around her death, this move to explain what drove her to an early grave at 47 is the film’s most humanistic touch. I wish that humanism had extended to the rest of the film.

This review was filed from the Toronto International Film Festival on September 17th, 2019.