This documentary directed by Lydia Tenaglia is a conspicuously imperfect movie that turns more compelling after trying your patience, then yields a final half-hour that’s as engrossing as a finely-wrought suspense drama. If you don’t already know who Jeremiah Tower is before seeing it, the opening moments are mystifying: an aging man, handsome and trim, wanders among ruins that seem Latin American (he is in Mexico, we will learn), all alone, and says, in voiceover, “I have to stay away from human beings because somehow I am not one.”

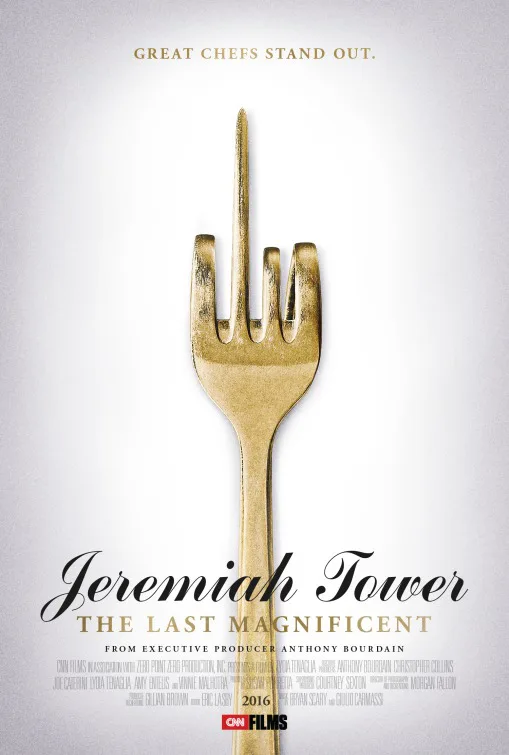

This is arguably a pretentious thing to say, and for a man who made his name feeding human beings, a very odd one. Jeremiah Tower is a chef who pioneered that thing we call New American Cuisine, and after his introduction, director Tenaglia brings out a Murderer’s Row of food-and-lifestyle figures to hammer home just what a heavy hitter Tower was and is. Martha Stewart, Ruth Reichl, Anthony Bourdain (who is one of the film’s executive producers), Mario Batali, Wolfgang Puck and others all sing his praises extravagantly. Terms such as “game changer” and “pioneer” are thrown around. “I want to thank you for not giving a f**k and going your own way,” a feisty young kitchen dude says at a filmed testimonial for Tower.

Tower’s professional life began at San Francisco’s’ Chez Panisse, whose founder, Alice Waters, is described here by one interviewee as wanting to “gather her rosebuds” while the more inclined-to-elegance Tower was more about putting on the white cuffs and snapping the whisk, or whatever the culinary equivalent of cracking the whip is. How Tower got that way is explained in an account of his early years that sees his affluent parents taking him on ocean voyages and to parties organized by the likes of Cecil Beaton. There is good late ‘40s early ‘50s archival footage—likely due to Tower’s dad being in the film equipment business—but a lot of the material here is in the form of arty staged reenactments, most of which look like outtakes from a “Mad Men” dream sequence or something. Combined with the Tower pronouncements of the early part of the movie, the air of stained seriousness grows very thick in the first 30 minutes.

But once Chez Panisse starts taking off in the ‘70s, and the storytelling starts to rely more and more on a proper talking-head Tower interview, interwoven with observations from, among others, the magnificently crusty food writer James Villas, “The Last Magnificent” becomes undeniably fascinating. Waters and Tower indeed were pioneers, and a lot of the farm-to-table ethos you hear about comes from their insistence in the case of Chez Panisse that locally sourced and/or American ingredients could constitute haute cuisine. “We don’t have to apologize that we’re using Dungeness crab,” Batali observes. “Our stuff is just as good,” continues Bourdain.

As the dual innovations of Tower and Waters are revealed, you’ll be wondering just why Alice Waters herself is not one of the interviewees … and you’ll find out. You’ll learn more about what feeds Tower’s notions of the impeccable—one of them being a preoccupation with the now almost entirely forgotten journalist/dandy Lucius Beebe. You’ll find out what he’s doing in Mexico at the film’s opening.

The story of Stars, Tower’s own San Francisco restaurant, is similarly juicy. One interviewee compares it to the Velvet Underground in terms of its actual lifespan relative to its massive influence. And then, once we think we’re up to date with Tower, he’s pulled out of his mysterious retirement in late 2014 … to take over the kitchen at a newly reopened Tavern on the Green.

As Bourdain says, it’s a real “WTF” moment. Tavern, while a New York landmark, was never a bastion of fine dining, and given its capaciousness, it seems logistically unlikely that it could be. I got the impression that the film was expressly commissioned to chronicle Tower’s comeback in this peculiar setting, and for the final section of the movie, Tenaglia and her crew are the flies on the wall as Tower’s immovable standards collide with co-owner Jim Caiola’s irresistible rights of proprietorship.

New Yorkers know how it came out. If you don’t, the scenes of Tower walking around Central Park in the dead of winter as his observations concerning a “horror of mediocrity” and an “abyss of slop” may qualify as foreshadowing. It is in this section, too, that Tenaglia reveals certain stories about Stars and its demise that might be perceived as her burying a couple of ledes. By this time, though, one is invested enough in the story that the annoyance is minor. Had the picture been more coherently organized, its appeal might be broader. As it is, gourmands (not “foodies”—that word never comes up here, and if it did, I suspect Tower might rightly condemn it as the sort of vulgarity he complains of being surrounded by) will avidly consume this very American story, the chaotic milieu of which is almost literally a world removed from the meditative one of a film like “Jiro Dreams of Sushi.”