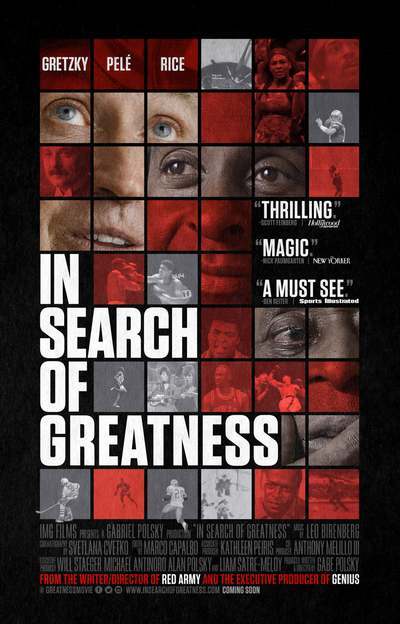

Hockey legend Wayne Gretzky says that parents often ask him to tell their children how much he practiced when he was their age, hoping he will inspire them to spend their afternoons doing drills. He explains why he won’t do that in a new documentary about what makes an athlete one of the all-time best from “Red Army’s” Gabe Polsky called “In Search of Greatness.”

Polsky has a distractingly tricked-up style. We really do not need to see footage of Lou Ferrigno as the Hulk to underscore a point about anger or Homer Simpson complaining that soccer is boring to emphasize the pressure to entertain the audience in sports. Archival clips of athletes, parents, and coaches are more illuminating. The film is a welcome tribute to vision, innovation, and knowledge as more important than technique and training, and encouraging imagination as more important for children than honing sports skills.

Gretzky spent hours after school practicing because it was what he wanted to do. He loved hockey. He did more than practice skating and shooting, too. He would watch hockey games with a drawing of the rink in front of him, and without looking down at it, he would trace the path of the puck. No one told him to do that. No one even thought of it before. When he was young, future NFL star Jerry Rice would lie in bed in the dark and toss the football up in the air over and over to learn how to intuit where the ball would be even if he could not see it. The movement of the football was a problem he had to solve.

Polsky explores the elements of once-to-a-planet greatness in interviews with GOATs (Greatest of All Time) stars Gretzky, Rice and soccer star Pelé, with comments from experts and archival clips. He touches on greatness in other fields like music and art, but the focus here is on sports, perhaps because measuring outcomes is quantitative and definitive. Anyone whose heavyweight boxing record is undefeated, 49-0, with 43 wins by knockout is unassailably great.

That record belongs to Rocky Marciano, and we learn in the film that on paper, he should not have been a champion. We think of size and reach as being crucial to performance in the ring, but Marciano was small for a heavyweight contender and his reach was 68 inches, as compared to Jersey Joe Walcott’s 74 inches. As we see with all of the athletes in the film, there were three key elements that make the difference.

First is problem-solving. Truly great performers love to solve problems, inventing new ways to score or play defense and turning their limitations into advantages. And they are very, very good at it. Marciano knew he had to get in close to deliver a punch powerful enough to win a fight, and developed a technique to make it work. The people at the top are innovators, like the Richard Douglas, who figured out before coaches and scientists did that doing a high jump backwards had better results. Parents and coaches may want their children to be the next Wayne Gretzky by copying his practice techniques, but the ones who are truly great invent their own. A young musician once asked Mozart for advice about writing a symphony. Mozart gently suggested he start with something less demanding, like a concerto. “You wrote a symphony at ten,” said the musician. “Yes, but I didn’t ask how.”

Second is determination. In the film we see GOAT skateboarder Tony Hawk fail repeatedly to make an unprecedented flip he was attempting in competition. But then, the competition over, he did not leave. He tried again for another eight minutes until he got it right. What mattered to him was not winning that particular competition; it was mastering the flip.

And the third is: they love it. As Gretzky said, he did not have to be pushed to practice. He tells us he can remember every shot of every game he’s ever been in. He compares that level of focus to kids who are naturally good at math, so the concepts are intuitive and memorized automatically. Whether he loves it because of whatever neurological makeup keeps those moments in his brain or remembers because he loves it, the movie should inspire each of us to think about what it is we find effortless to remember and how that should guide our priorities.

There are several references to the NFL Scouting Combine, an invitation-only event for college football players, who run, jump, and bench press in front of NFL coaches making their draft decisions. No one in this film thinks that the Combine is a useful indicator of a player’s performance in professional football, with footage of Tom Brady’s unimpressive results a pointed reminder of how misleading it can be. Standing broad jumps and 40-yard dashes are not good predictors of an athlete’s ability to work seamlessly with a team. As Gretzky says in the film, he may not be the fastest in skating around the rink but he is the fastest in getting to the puck, which requires a deep understanding of the physics and geometry and the ability to make those calculations very, very quickly.

We are more likely to place weight on what we can measure because we can measure it than because it tells us anything meaningful. More important, the movie shows us that instead of pushing children to be like Wayne Gretzky by practicing hockey every afternoon, they should be like Gretzky, Rice, and Pelé by finding something they love and working to make not just themselves better but to make what they love better, too.