Norman Jewison’s “In Country” is constructed like a short story, not a novel. It sneaks up on us with a series of incidents from daily life – moments that don’t seem to be leading anywhere in particular, until we’re blind-sided by the surprising emotional impact of the closing scene.

It’s not about conflict between characters, but about people in the process of learning about themselves.

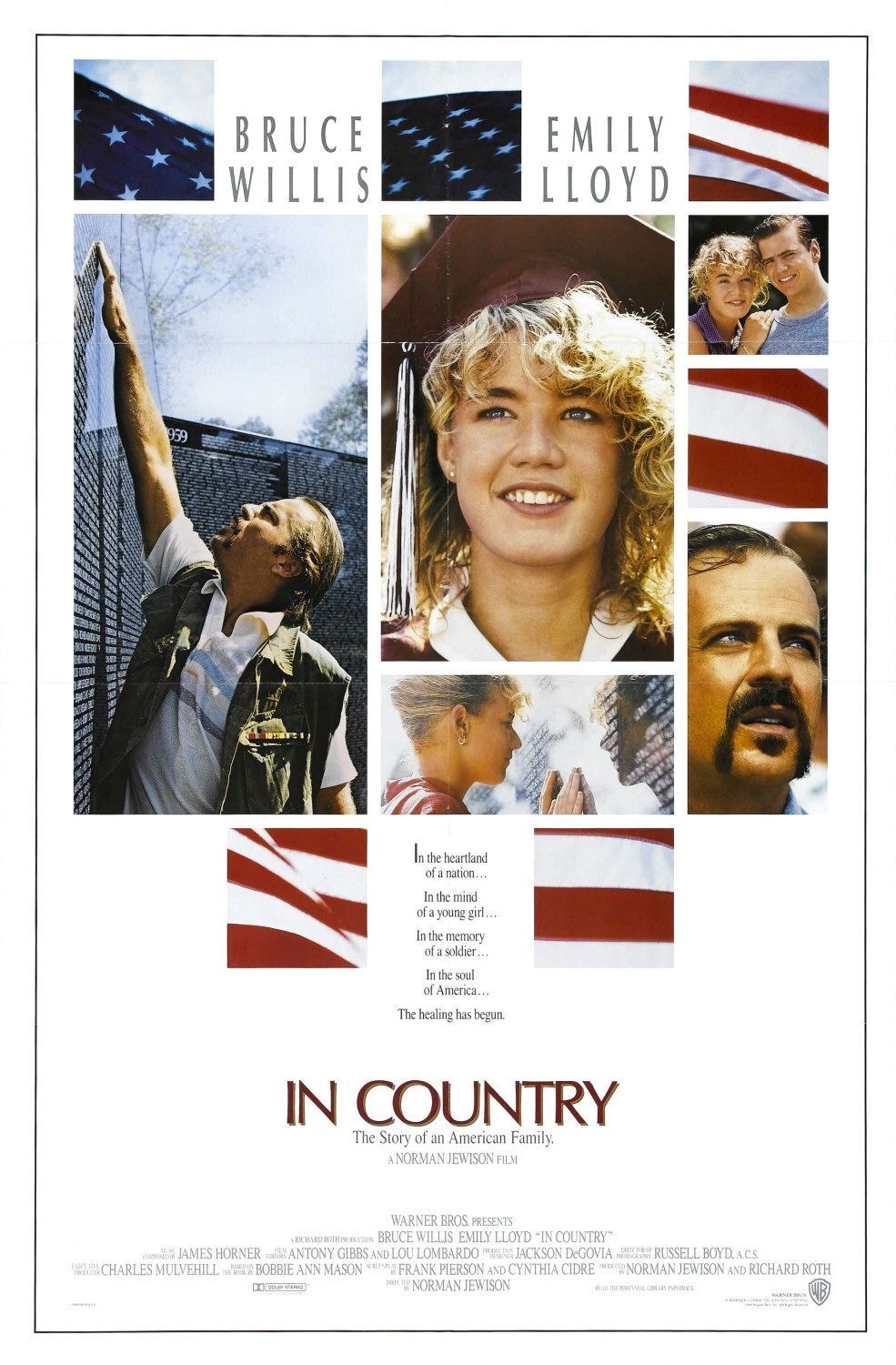

The film’s central character is a 17-year-old girl named Samantha (Emily Lloyd), who is living in the small town of Hopewell, Ky., with her uncle. He’s a guy named Emmett (Bruce Willis), who fought in Vietnam and has spent the years since then wandering in sort of detached silence, and watching a lot of television. Samantha’s father was killed in Vietnam before she was born. Her mother (Joan Allen) has remarried.

In the course of the story, Sam is confronted by no less a question than the meaning of birth and parenthood. She wants to know more about her father, and finds some of his letters home. There are some old photographs, too, of a soldier barely older than she is now – a 19-year-old in a private’s uniform. Sometimes she talks to the photograph, telling her father of some of the things he missed by being killed in Vietnam, things like listening to Bruce Springsteen.

Other events happen, connected to the notion of parents and children. Sam’s own mother visits, with her young daughter. One of Sam’s friends gets pregnant, and has to decide what to do. All of these events seem to circle the key question in Sam’s life: Who was her father, and what did his life and death mean? “Honey,” her mother tells her, in the movie’s saddest line, “I married him four weeks before he left for the war. I was 19. I hardly even remember him.” Sam begins to wonder if it is her uncle Emmett, the Vietnam survivor, who can provide the key to her questions. Emmett isn’t the kind of stereotyped Viet vet who has become a staple in action movies: the crazed nut case who runs amuck with a machinegun. He has disappeared inside his own passivity, and seems content to let his life slip through his fingers. She tries to awaken him, with questions, and even through a dance the local people sponsor in “belated appreciation” for the boys who fought the war.

All of these episodes (and others, involving Sam’s grandparents) create emotional momentum without revealing where they’re leading us.

The movie is not constructed in the usual ways, with clear milestones in the plot. It is only at the end, when Sam and Emmett and Sam’s grandmother (Peggy Rea) go to visit the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, that we see what the movie has been leading up to. It’s there, in a scene of amazing emotional impact, that Jewison releases all of the emotional tension, all of the sadness and bewilderment, that has been piling up during the film.

“In Country” is based on the novel by Bobbie Ann Mason, and Jewison is faithful to its accumulation of small incidents involving ordinary people. It is the fact that the ending is so low-key that makes it work so well (“Let’s go get us some of that barbecue,” the grandmother suggests, after they’ve finished their visit to the memorial). The film should almost list the Vietnam Memorial in its credits, it works so effectively as a focus for the emotion.

Lloyd is astonishing in the film’s leading role. A young actress from London with only two previous roles in her credits (“Wish You Were Here” and “Cookie“), she masters not only the Kentucky accent but the whole feeling of Sam: her gawkiness, her energy, the power of her curiosity. Willis has less showy scenes (the character of Emmett is the opposite of every other character Willis has ever played), but he is well cast, almost disappearing into the sad, silent survivor. The movie is like a time bomb. You sit there, interested, absorbed, sometimes amused, sometimes moved, but wondering in the back of your mind what all of this is going to add up to. Then you find out.