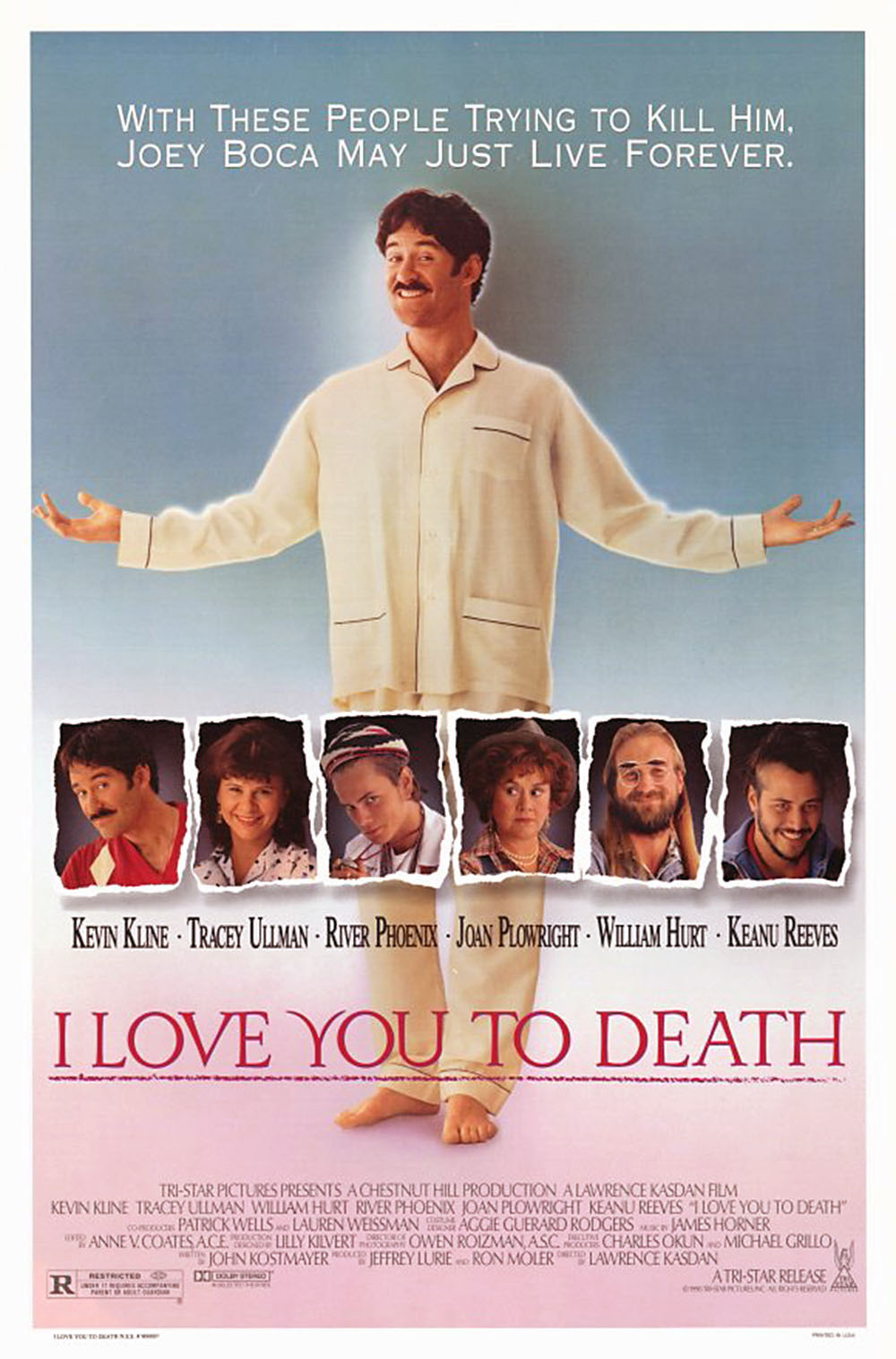

“I Love You to Death” is like an acting class in which the students are presented with impossible situations and asked how they would handle them. The students in this case are accomplished actors – Kevin Kline, William Hurt, Tracey Ullman and Joan Plowright, among others – but what was each one thinking in the scene where the dead man walks downstairs? How do you carry on a polite conversation with someone who has a bullet hole clean through him, but hasn’t noticed? Particularly if you were involved in his attempted murder? The movie’s plot is so unlikely that of course it is based on fact. The story was in the news a couple of years ago, about how the wife of a pizzeria owner decided to kill her husband because he was cheating on her. After the murder attempt failed, the husband refused to press charges against his wife because he felt she had done the right thing. After all, he was guilty, wasn’t he? My memory is hazy about what happened then. They lived happily ever after, most probably.

In the movie version, written by John Kostmayer and directed by Lawrence Kasdan, this story is developed into a domestic black comedy of droll and macabre dimensions. And it is told in a series of scenes in which most of the characters are either lying to each other, lying to themselves, or incapable of coherent thought. The few moments of honesty and lucidity have a fascination all their own, since under those conditions the characters tend to become tongue-tied with embarrassment.

The result is an actor’s dream, a film in which the truth of almost every scene has to be excavated out of the debris of social inhibition. I am not so sure this is a dream film for an audience, however; the moviegoer eager for plot and drama is likely to grow impatient and think nothing much is happening on the screen, when in fact volumes are happening inside the minds and consciences of the characters.

The movie begins with a happy day at the pizzeria in Tacoma, Wash., where Joey (Kevin Kline) and his wife Rosalie (Tracey Ullman) take care of business with the help of Devo (River Phoenix), who is very, very far out, but who occasionally focuses on the object of his devotion, Rosalie. Joey is a ladies’ man. Cheerfully shouldering his kit of plumber’s tools, he sallies forth daily to do “odd jobs” in the rental apartments the family owns – most of them occupied by willing females whose plumbing is in fine repair. It should be obvious to anyone that Joey is cheating, but Rosalie remains blissfully blind to the evidence. She trusts her Joey.

The moment of her awakening is a painful one. She feels betrayed and double-crossed. She confides in her mother (Joan Plowright), and they agree, without hesitation, that the death penalty is called for in this case. They dispatch the faithful Devo to a local pool hall, where two low-life drugheads (William Hurt and Keanu Reeves) are bent low over the pool table, for support.

They agree to shoot Joey, for a price. Meanwhile, Rosalie and her mother have fed the philandering husband several helpings of spaghetti laced with three large bottles of sleeping pills.

The drugheads arrive, hold a confused conference at the bedside, and shoot the slumbering victim. Then, while everyone is conferring downstairs, Joey appears, still alive. The movie’s most difficult and intriguing scene now follows. It takes place almost entirely in the eyes of the actors, and in their pauses and silences, and is an exquisite exercise in guilty embarrassment. It is an almost impossible scene to pull off, but somehow they accomplish it.

Another good thing about the movie is Tracey Ullman’s low-key, plain-Jane approach to the wife. It’s all the more effective because Kevin Kline has for some reason adopted a comic opera accent and mannerisms as the husband, and is hard to believe except in the scenes where he is almost dead.

Ullman finds the stubborn vindictiveness inside her character, who is so sunny when she trusts her husband and so unforgiving when she discovers she was deceived. Joan Plowright might seem like an unlikely choice as the mother, but gets the movie’s biggest laugh in a bedside scene. William Hurt could have walked through the role of the spaced-out hit man, but takes the time to make the character believable and even, in a bleary way, complex.

Nothing in Lawrence Kasdan’s previous career (“Body Heat,” “The Big Chill,” “Silverado,” “The Accidental Tourist“) seems like preparation for this film, but then what could? It is the first time Kasdan has directed from a screenplay he didn’t write, and I assume he was attracted to it for the obvious reason – because it seemed all but impossible to do. I am not sure if the film is a success because I am not sure what it is trying to do. It founders in embarrassment, but not boringly.