Set in a town in Brianza and in Milan, mostly on the night before the night before Christmas, “Human Capital” is the kind of movie that embeds the significance of its title into every subplot, then defines it in an onscreen title at the end, just to make sure you got it. Essentially “American Beauty, Italian Style,” with a similar “Ah, sweet magical mystery of life!” score and an artfully scrambled timeline, this ensemble drama about troubled upper-middle class strivers is slick, confident, and rather empty, and structurally more self-defeating than clever.

The script slides back and forth along a timeline, always returning to the script’s central gathering place, a private school student awards ceremony/dinner after which a waiter is hit by a car while bicycling home. This is supposed serve as a Macguffin, stoking a sense of mystery and anticipation: Which person (or persons) hit the waiter? Why didn’t they cop to it? How to they plan to escape punishment?

But as the movie unreels—leaping from one character and subplot to another, as one might explore different Wikipedia biographies by clicking on hypertext-linked names—the movie runs out of gas, and your attention wanders instead to the individual characters, their world, and the themes that writer-director Paolo Virzi (“Napoleon in the City,” “Every Blessed Day”) tries too strenuously to explore: the oblivious arrogance of the One Percenters; the way greed tends to drown out decency; modern capitalism’s tendency to treat everything, including people, as raw material to be bought, consumed, or discarded.

The ensemble cast is strong, though; their performances and Jérôme Alméras’s cinematography ensure that “Human Capital” remains watchable even after you feel you’ve gotten the point already and the movie is belaboring it. Fabrizio Bentivoglio brings a Jack Lemmon-like wheedling desperation to the role of Dino Ossola, a local real estate success story who borrows seven hundred thousand Euros to buy into a supposedly high-yield hedge fund. The fund is overseen by Giovanni Bernaschi (Fabrizio Grifuni), a filthy rich investor who lives in a mansion with a marble driveway. He’s connected to Dino through his teenage son Massimiliano (Guglielmo Pinelli), who attends the aforementioned private school with Dino’s lovely, kindhearted daughter, Serena (Matilde Gioli).

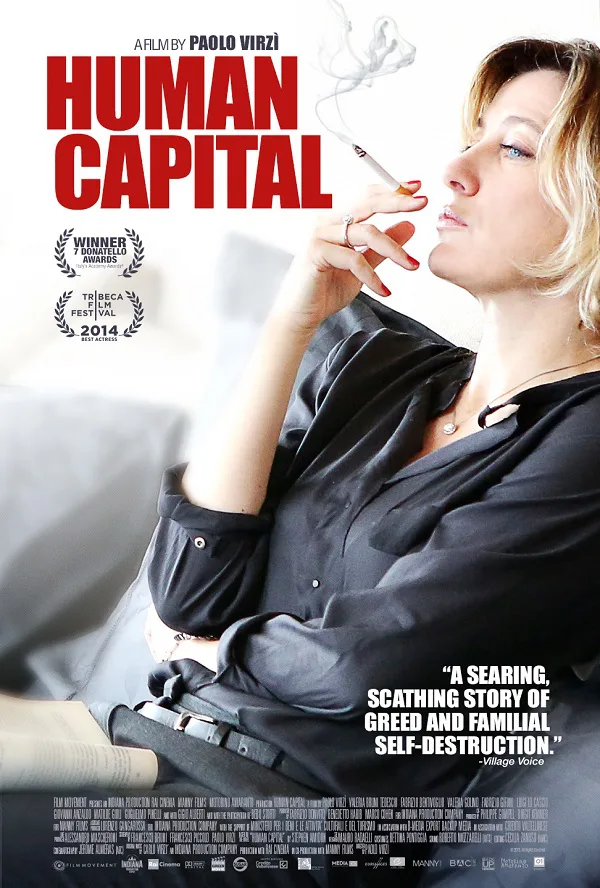

Giovanni is a classic money-grubbing cinematic yuppie. He’s always seen in an expensive suit and tie or in silk robes that probably cost more than some people’s cars; why they didn’t just give him a top hat and monocle is beyond me. His wife Carla (Valeria Bruna Tedeschi) is a onetime actress morally numbed by abandoning her art and spending her days spending her husband’s money. When she convinces Giovanni to buy and rescue a doomed local theater for her to restore, it rekindles her sense of possibilities, and sparks a powerful attraction between her and one of the theater’s trustees, the idealistic college professor Luigi Lo Cascio (Donato Russomanno).

There are more characters where these came from. They’re connected by the central question of who hit the cyclist, as well as by the (often tangentially) related themes of greed, poor impulse control, and guilt (or the lack thereof). Nearly every major character is harboring a devastating secret which, if exposed, could ruin them or bring shame to their families.

This sounds like a tasty recipe for a domestic melodrama, but Virzi avoids any filmmaking that might suggest overwhelming passion or messiness. The movie is as neat and tidy as can be, every character slotted into a particular section, every repeated scene marked on an unseen master timeline, every lesson reflecting every other lesson. The photography is elegant and tasteful, especially during long confrontations between two characters that are shot in unbroken, claustrophobic takes; but maybe elegant and tasteful were the wrong values to embrace? This material about repressed rich and near-rich people cries out for some visual or rhythmic instability—a sense that the normal patterns (of storytelling as well as life) have been disrupted, destroyed, rewritten. What’s onscreen feels rote, clean, safe. All the puzzle pieces drop into place one-by-one, because the filmmaker knows what the finished picture will be.

The performances are superb, with the conspicuous exception of Pinelli, whose overwrought acting plays like a tone-deaf parody of wealthy teenage entitlement. Tedeschi’s Carla is the film’s most affecting character, a once-passionate woman tamed by comfort and only now reawakening, at long last. If the entire film had been about her, I wouldn’t have minded; it would’ve at least given us more time with Tedeschi, an actress whose transparency of feeling bonds us to her. Instead, the picture feels like what a critic friend calls a “tax shelter movie”: hire a lot of name actors of different generations, put them in a modestly budgeted ensemble movie with interlinked subplots so that everyone gets a “big” moment or two, tie it all together with a Big Idea, and voila: commercial art. That’s “Human Capital,” a film whose title resonates in all the wrong ways.