A few days after Allen Ginsberg died in 1997, there was a candlelight memorial service in a coffeehouse in Boulder, Colo., just down Pearl Street from Beat Book Shop. Ginsberg was familiar in Boulder as founder of the wonderfully named Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University. Poets read their work and his, listeners sat on chairs or on the floor, and for that time, the beatnik era lived again.

The Beats created poetry, fiction, art and music, but most of all, they created the legend of themselves — “angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night.” After rock ’n’ roll, they were the first decisive break with the orderly postwar years, and following them were the hippies, Woodstock, flower power, the Me Generation and adults wearing Levis to the office. For anyone young in the late 1950s — a kid at Urbana High School, for example — to read the opening words of Ginsberg’s “Howl” was to know — yes! — that they described you: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn.”

Yes. Not that one was, but that one wanted to think of oneself in such terms. You wanted to steal the family car and drive all night and into the burning sun, driven by caffeine, and drive without stopping directly to City Lights bookstore in San Francisco, and have Lawrence Ferlinghetti publish your poems, which you would have scribbled on legal pads on the seat next to you as you drove.

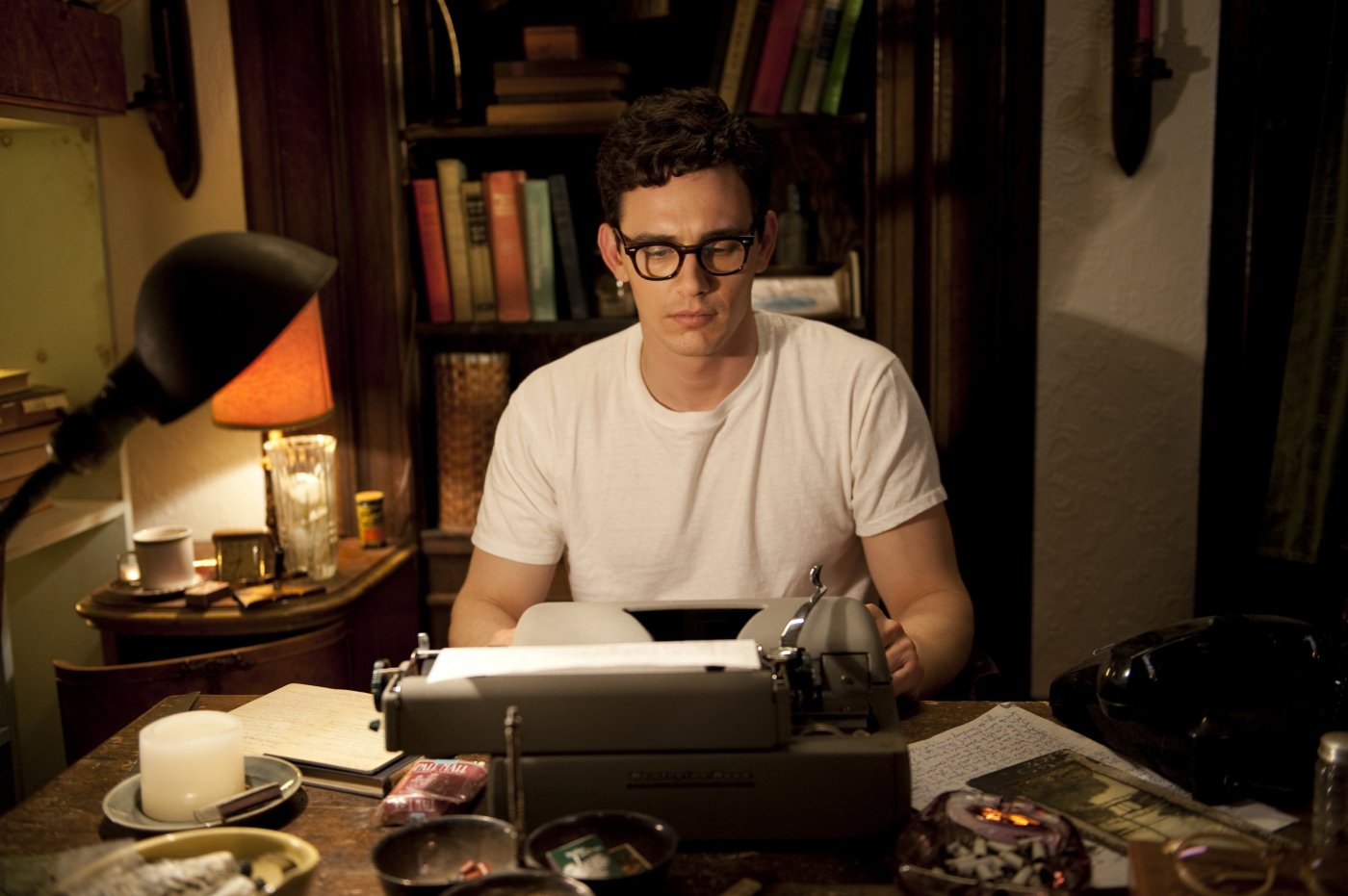

The film “Howl” evokes the first tender birth of that new age. Its Beats still wear jackets and ties. Allen Ginsberg has horn-rimmed glasses and seems touchingly young, and not at all an angelheaded hipster destroyed by madness. The secret was: He wanted to be one, too. As the film gently reveals, he was reluctant to have his great early poem published, because he wasn’t eager to have his daddy find out things about him, such as that he was homosexual.

In years to come, Allen Ginsberg would play the role of Public Poet as Robert Frost had for an earlier and much different generation. He was Out when other brave souls were still only opening the closet door and waving. At a National Student Congress, I saw him sit cross-legged on a rug and use finger cymbals and chant whatever it was he was chanting, because the act and not perhaps the words seemed to be the point.

What feels right about “Howl” is that it is set before those days, before the beard and the mysticism and Tibet and the public persona and the levitating of the Pentagon. The bold, outspoken man of later days is seen here as still a middle-class youth, uncertain of his gayness, filled with the heady joy of early poetic success, learning how to be himself.

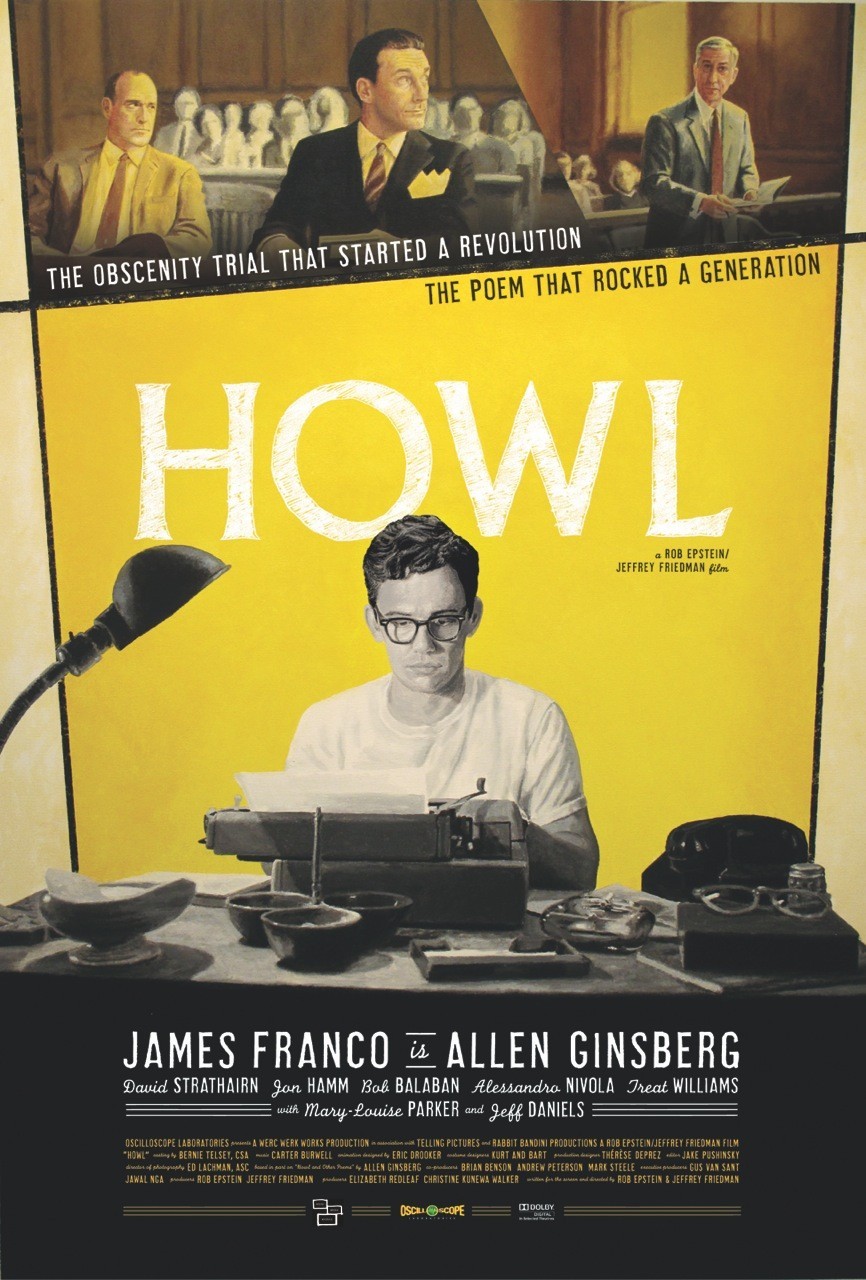

The film is above all about “Howl” the poem. Ginsberg, played by James Franco with restraint and care, reads it as smoke fills a 1955 coffeehouse. There is a re-creation of an early Ginsberg documentary interview. We see scenes from the poem’s trial for obscenity, with David Strathairn for the prosecution and Jon Hamm for the defense. (As ludicrous as some of the testimony is, it must be noted it’s word-for-word from the transcript.) There is an uncertain attempt to animate some passages from “Howl,” based on the miscalculation that the poem’s striking imagery needs visuals, not words, to be realized.

Then there are straightforward biographical scenes involving Ginsberg’s friendships with such Beats as Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady, the charismatic legend who was the inspiration for the Dean Moriarty character in On the Road. It is during this time Ginsberg meets the man with whom he would spend the rest of his life, Peter Orlovsky. All of the biographical material is wisely done without the benefit of hindsight: It’s possible to forget that “Howl,” now a standard, was illegal to sell for a time, and that Ginsberg’s own sexuality was against the law in many states. It took some courage to be Allen Ginsberg.

One of the qualities I like about this film is that the writer-directors, Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, are aware of the time when Beat scene was new. The coffeehouse reading could be archival footage. The re-created obscenity trial preserves the prim academic standards of the day (even in the 1960s, someone like Auden was not quite acknowledged as gay). The animation could be from an overheated student film. And the Orlovsky scenes focus more on idealized romance. Ginsberg also had a crush on Kerouac, who is seen here in much the same macho way as the early Brando and Newman: a hunk — but perfectly straight, of course.