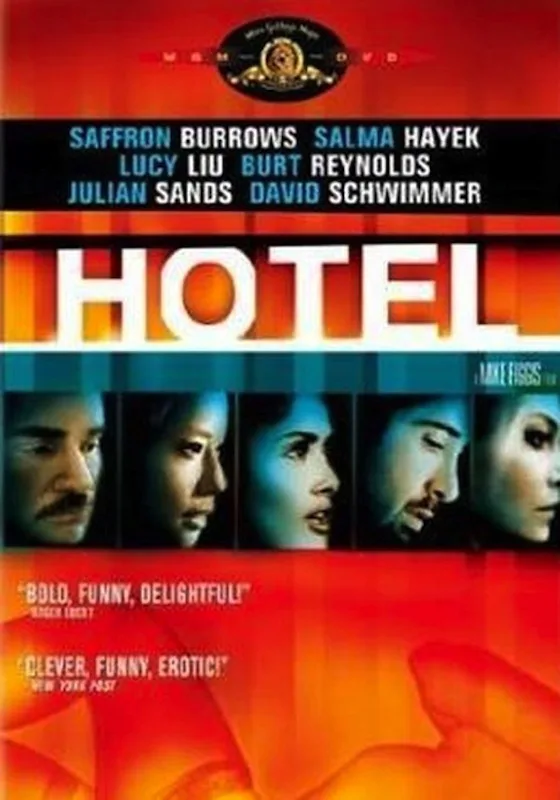

Here’s a strange case. “Hotel” is a movie that works in no conventional sense, and succeeds in several unconventional ones. Most audiences will find it baffling and unsatisfactory. Those who are open to its flywheel peculiarities may find it bold, funny, peculiar and delightful. The director is Mike Figgis, whose conventional thriller “Cold Creek Manor” opened last week. I would a hundred times rather see “Hotel.” The movie is told like three stories running in a circle, snapping at each others’ tails. One story involves a self-important movie director named Trent Stoken (Rhys Ifans), who is in Venice shooting a version of John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi in the Dogma style. The second involves a documentary crew led by Charlee Boux (Salma Hayek) that is making one of those “making of” films about the production. The third involves the workings of the hotel itself, which is run by and for cannibal vampires. All of this is much in the spirit of Webster, Shakespeare’s contemporary, whose plays drip-ped with violence, melodrama, conspiracy and sexual intrigue.

Figgis is a bold experimenter whose films often leave conventional pathways to achieve their effect. His “Leaving Las Vegas” (1995) was shot on Super 16mm so that the cast and crew could work quickly on locations without clearances or permits. His “Timecode” (2000) was shot on digital video that used a four-way split screen to tell the story with four simultaneous and unbroken shots (Aleksandr Sokurov’s “Russian Ark” had only one 90-minute take). In “Hotel,” made in 2001 but just now receiving a U.S. release, Figgis shows the film-within-a-film on digital video, goes outside it with conventional celluloid, and sometimes presents the same scene with messy location sound and then polished post-production sound.

Now imagine all this stylistic freedom with an all-star cast of actors invited to play broadly, wryly, erotically. There is a feud between the Ifans character and his producer (David Schwimmer), and a stunning moment when the director is shot, only to linger in a long, eyes-open coma that inspires an extraordinary erotic monologue by his nurse (Chiara Mastroianni). Saffron Burrows plays the Duchess of Malfi and is involved first with Ifans, then with Schwimmer.

Familiar faces are everywhere: Lucy Liu as an instinctive enemy of Hayek; Danny Huston as the helpful, sinister hotel clerk; Julian Sands as the tour guide, whose explanations of Venice and the Webster play provide a road map; Valeria Golino as another of the actresses, and Burt Reynolds, who convincingly occupies what seems to be a completely superfluous role. Used most oddly of all is John Malkovich, in an opening sequence where he is taken down into the catacombs of the hotel and participates in a formal feast where, it becomes clear, the main dish is human flesh. Malkovich’s seat at the table, ominously, is behind bars separating it from the others.

The movie does a fair job of satirizing the conceits of the Dogma movement — showing the hapless Burrows trying to perform period costume scenes in the middle of a Piazza San Marco filled with rubbernecking tourists. It shows the competition for power, money and sex that can take place when gigantic egos are assembled. It has more than one unusually erotic scene, including a monologue as evocative as the one in Bergman’s “Persona.” Salma Hayek finds more than a documentarian could hope for, when she wanders into hidden passages and discovers dismembered body parts. The treatment of the comatose director is cruel, funny, sad and creepy. The fact that all of these characters are being preyed on by vampires may be a metaphor for the megacorporations that own the movie industry. Or maybe not.

Many critics have agreed that “Hotel” is not successful, but I would ask: Not successful at what? Before you conclude that a movie doesn’t work, you have to determine what it intends to do. This is not a horror movie, a behind-the-scenes movie, a sexual intrigue or a travelogue, but all four at once, elbowing one another for screen time. It reminds me above all of a competitive series of jazz improvisations, in which the musicians quote from many sources and the joy comes in the way they’re able to keep their many styles alive in the same song. Figgis is a musician (he composed for the film, in addition to co-writing, co-photographing and co-producing). Maybe that occurred to him. There is a heady freedom in his riffs here that might appeal to you, if you don’t doggedly insist that everything reduce itself to the mundane. The movie has to be pointless in order to make any sense.