“Cold Creek Manor” is another one of those movies where a demented fiend devotes an extraordinary amount of energy to setting up scenes for the camera. Think of the trouble it would be for one man, working alone, to kill a horse and dump it into a swimming pool. The movie is an anthology of cliches, not neglecting both the Talking Killer, who talks when he should be at work, and the reliable climax where both the villain and his victims go to a great deal of inconvenience to climb to a high place so that one of them can fall off.

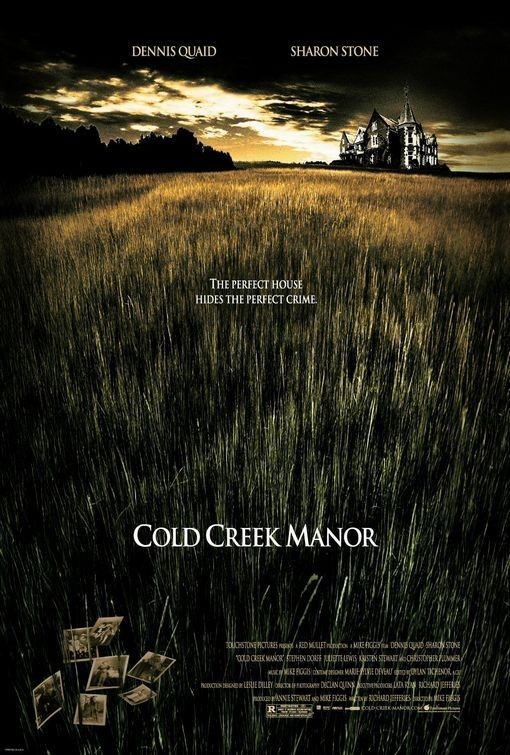

The movie stars Dennis Quaid and Sharon Stone as Cooper and Leah Tilson, who get fed up with the city and move to the country, purchasing a property that looks like the House of the Seven Gables crossed with the Amityville Horror. This house is going to need a lot of work. In “Under the Tuscan Sun,” another new movie, Diane Lane is able to find some cheerful Polish workers to rehab her Tuscan villa, but the Tilsons have the extraordinarily bad judgment to hire the former owner of the house, Dale Massie (Stephen Dorff), an ex-con with a missing family. “Do you know what you’re getting yourselves into?” asks a helpful local. No, but everybody in the audience does.

The movie of course issues two small children to the Tilsons, so that their little screams can pipe up on cue, as when the beloved horse is found in the pool. And both Cooper and Leah are tinged with the suggestion of adultery, because in American movies, as we all know, sexual misconduct leads to bad real estate choices.

In all movies involving city people who move to the country, there is an unwritten rule that everybody down at the diner knows all about the history of the new property and the secrets of its former owners. The locals act as a kind of Greek chorus, living permanently at the diner and prepared on a moment’s notice to issue portentous warnings or gratuitous insults. The key player this time is Ruby (Juliette Lewis), Dale’s battered girlfriend, whose sister is Sheriff Annie Ferguson (Dana Eskelson). She smokes a lot, always an ominous sign, and is ambiguous about Dale — she loves the lug, but gee, does he always have to be pounding on her? The scene where she claims she wasn’t hit, she only fell, is the most perfunctory demonstration possible of the battered woman in denial.

No one in this movie has a shred of common sense. The Tilsons are always leaving doors open even though they know terrible dangers lurk outside, and they are agonizingly slow to realize that Dale Massie is not only the wrong person to rehab their house, but the wrong person to be in the same state with.

Various clues, accompanied by portentous music, ominous winds, gathering clouds, etc., lead to the possibility that clues to Dale’s crimes can be found at the bottom of an old well, and we are not disappointed in our expectation that Stone will sooner or later find herself at the bottom of that well. But answer me this. If you were a vicious mad-dog killer and wanted to get rid of the Tilsons and had just pushed Leah down the well, and Cooper was all alone in the woods leaning over the well and trying to pull his wife back to the surface, would you just go ahead and push him in? Or what? But no. The audience has to undergo an extended scene in which Cooper is not pushed down the well, in order for everyone to hurry back to the house, climb up to the roof, fall off, etc. Dale Massie is not a villain in this movie, but an enabler, a character who doesn’t want to kill but exists only to expedite the plot. Everything he does is after a look at the script, so that he appears, disappears, threatens, seems nice, looms, fades, pushes, doesn’t push, all so that we in the audience can be frightened or, in my case, amused.

“Cold Creek Manor” was directed by Mike Figgis, a superb director of drama (“Leaving Las Vegas“), digital experimentation (“Timecode”), adaptations of the classics (“Miss Julie“) and atmospheric film noir (“Stormy Monday“). But he has made a thriller that thrills us only if we abandon all common sense. Of course preposterous things happen in all thrillers, but there must be at least a gesture in the direction of plausibility, or we lose patience. When evil Dale Massie just stands there in the woods and doesn’t push Cooper Tilson down the well, he stops being a killer and becomes an excuse for the movie to toy with us — and it’s always better when a thriller toys with the victims instead of the audience.