“Holy Smoke” begins as a movie about the deprogramming of a cult member and ends with the deprogramming of the deprogrammer. It’s not even a close call.

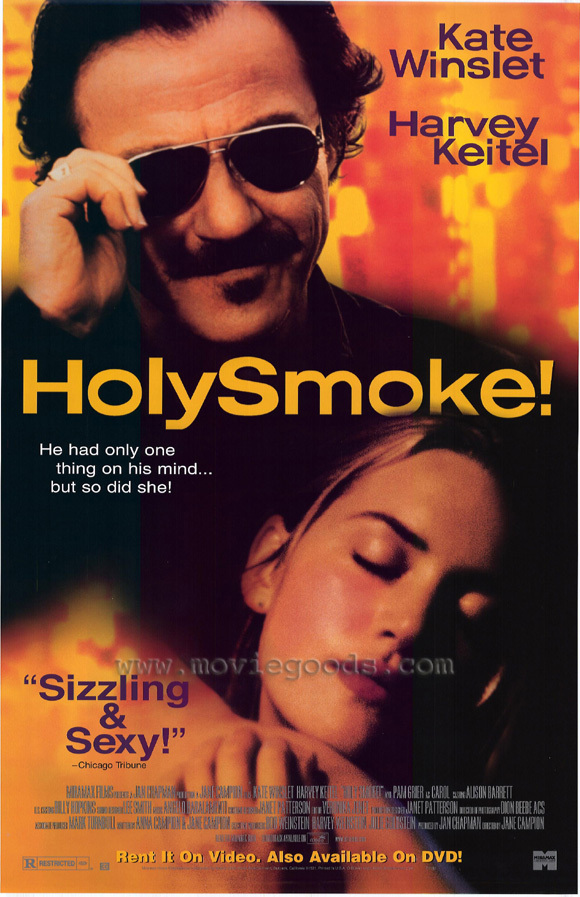

The cult member is Ruth (Kate Winslet), an Australian who has gone to India and allied herself with a guru. And the deprogrammer is Harvey Keitel, summoned by Ruth’s parents; he stalks off the plane like his no-nonsense fix-it man in “Pulp Fiction” and then starts falling to pieces. The movie leaves us wondering why the guru didn’t become Ruth’s follower, too.

The film isn’t really about cults at all, but about the struggle between men and women, and it’s a little surprising, although not boring, when it turns from a mystic travelogue into a feminist parable. The director is Jane Campion (“The Piano“), who wrote the screenplay with her sister Anna. Like so many Australian films (perhaps even a majority), “Holy Smoke” suggests that everyone in Australia falls somewhere on the spectrum between goofy and eccentric, none more than characters invariably named Mum and Dad. Parents are totally unhinged beneath a facade of middle-class conventionality; their children seem crazy, but like many movie mad people, are secretly saner than anyone else. Campion’s first film, “Sweetie,” was an extreme example; “Holy Smoke” reins in the strangeness a little, although to be sure there’s a scene where Keitel wanders the outback wearing a dress and lipstick, like a passenger who fell off “The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert.” Ruth, the Winslet character, journeys to India and falls under the sway of a mystic guru. Her parents trick her into returning, and hire P.J. Waters (Keitel) to fly over from the United States and deprogram her. At this point I was hoping perhaps for something like “Ticket to Heaven” (1981), the powerful Canadian film about the struggle for a cult member’s mind. But no. The moment Ruth and P.J. face off against each other, their struggle is not over cult beliefs, but about the battle between men and women. And P.J., with his obsolete vocabulary of sexual references, is no match for the strong-willed young woman who overwhelms him mentally, physically and sexually.

Winslet and Keitel are both interesting in the film, and indeed Winslet seems to be following Keitel’s long-standing career plan, which is to go with intriguing screenplays and directors and let stardom take care of itself. That may mean he doesn’t get paid $20 million a picture, but $20 million roles, with rare exceptions, are dogs anyway–because they’ve been chewed over and regurgitated by too many timid executives. A smaller picture like this, shot out of the mainstream, has a better chance of being quirky and original.

And quirky it is, even if not successful. Maybe it’s the setup that threw me off. Ruth comes onscreen as one kind of person–dreamy, escapist, a volunteer for mind-controlling beliefs–and then turns into an articulate spokeswoman for Jane and Anna Campion’s ideas. It’s also a little disappointing that the film didn’t penetrate more deeply into the Indian scenes, instead of using them mostly just as setup for the feminist payoff.

And it’s difficult to see how the Ruth at the end of the film could have fallen under the sway of the guru at the beginning. Not many radical feminists seek out male gurus in patriarchal cultures.