Pedro Almodovar’s films are an acquired taste, and with “High Heels” I am at last beginning to acquire it. Although the fashionable Spanish director’s most famous film, “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown,” is a favorite of many people, I had a curious experience with it: I simply could not engage it.

I saw it once, twice, three times finally in frustration and despair, and yet was unable to relate to anything on the screen. It slipped past me insubstantial as a ghost. His next film, “Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!,” seemed like one of those meaningless exercises the writers in the New York weeklies call “postmodernism,” as if that explained anything.

But now here is “High Heels,” a film of great color and vitality, and while it is transcendentally silly, I rather enjoyed that quality. It’s a tongue-in-cheek melodrama of cheerfully ridiculous implausibility, involving the lurid lives and loves of a flamboyant actress, her emotionally fraught daughter, and the people in love with them. But even in that sentence I have played a little trick, since the “people” in love with them are fewer than it seems, through a surprise that I will not destroy for Almodovar.

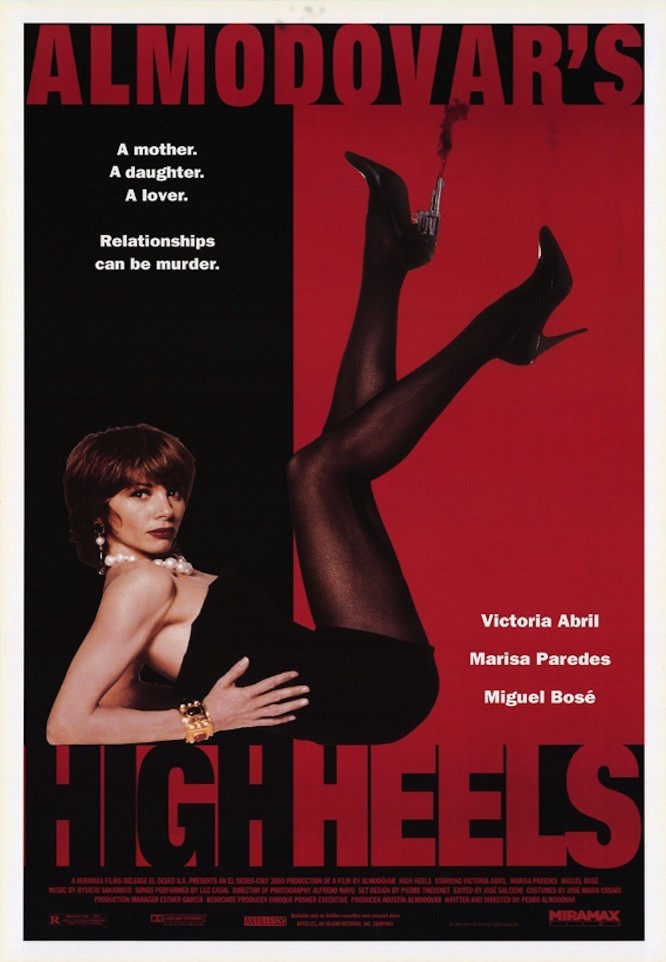

The film stars Marisa Paredes as Becky Del Paramo (why does that name make me think of a female impersonator?), and Victoria Abril as her daughter. After subjecting her child to an upbringing of tempestuous upheaval, Del Paramo is liberated from her husband by his convenient death (hastened helpfully by the daughter). She flies off to Madrid, I believe it is, to become a great cult star, while the daughter, left behind, becomes a TV anchorwoman and marries one of her mom’s old flames.

Almodovar’s screenplay is written like one of those soap operas in which the characters are assembled in first one and then another combination until all of the possibilities are exhausted.

Since many of the characters in this movie have more than one sex and more than one name, there are more possibilities than you might expect, but, yes, I think it would be fair to say that by the end they are indeed exhausted.

Almodovar and his cinematographer, Alberto Mayo, photograph his films with the eyes of graphic artists. He likes bold blocks of bright colors, and costumes of reds and yellows, shocking pinks and electric blues. There is a scene in the film showing nothing more than a woman driving in a car, but Almodovar films it next to a long abstract mural, so that his trademark colors unfold in the background, through the window.

The acting style of his work seems inspired by the films of Douglas Sirk and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, filtered through “Dynasty.” His actresses all seem inspired by (or inhabited by) Joan Crawford and Bette Davis, his actors seem almost deliberately like B-movie leading men, and the plots involve characters who get more upset over their own aging process than over, let us say, the deaths and tragedies of others.

Like Sirk and Fassbinder, Almodovar finds humor in the deadpan depiction of reality, as in a scene where the daughter sits at an anchor desk and reports the death of her husband. Sitting next to her is another young woman, who was having an affair with the husband, and who is translating the newscast into sign language. This scene develops into truly inspired comedy.

An Almodovar film is always an exercise in style, but “High Heels” also generates narrative energy and mystery, and provides what was, for me, a genuine surprise at the end. Like the self-contained musicals and Technicolor “women’s pictures” of the 1940s, this movie perhaps has no other ambition. It is like a painting or a graphic design, creating a world that exists only in its own terms, that does not understand the full range of human emotion, or care to. But it is accomplished with wit, style and outrage, and although it is all smoke, feathers and laughter, it works.