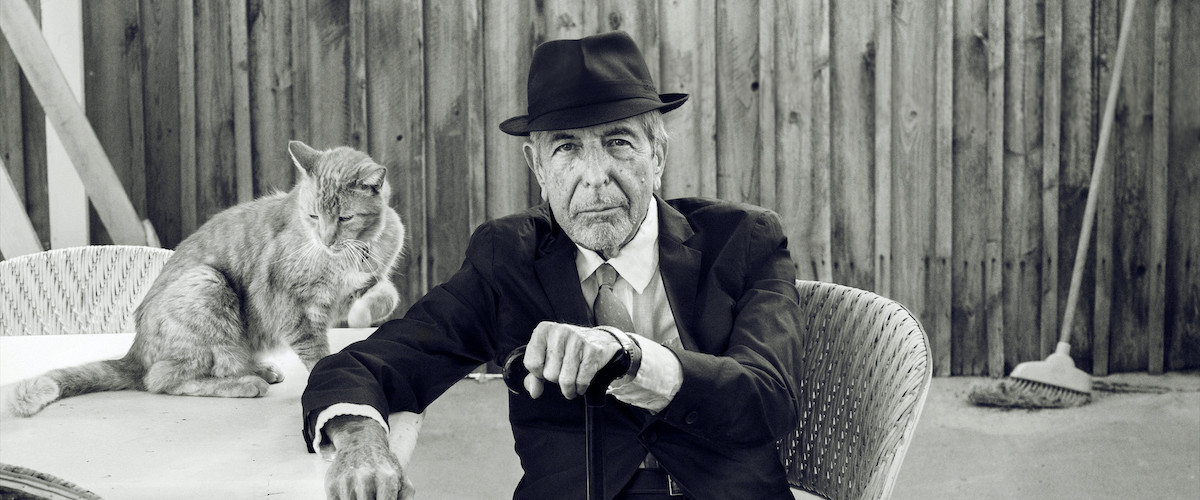

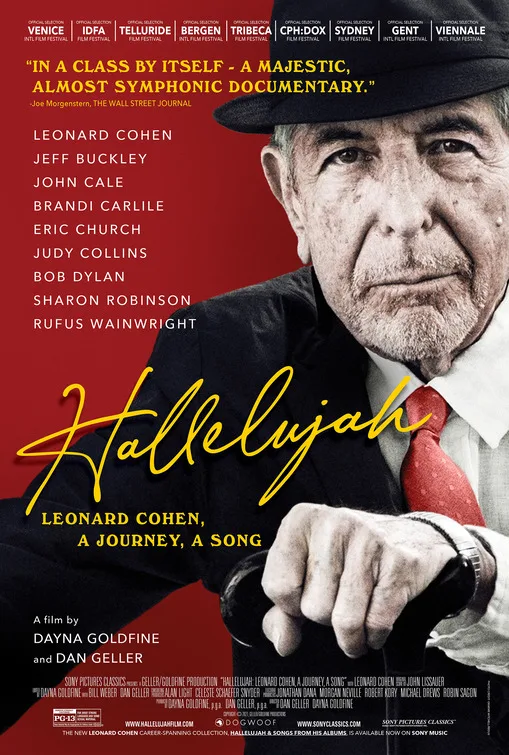

The unfocused biographical doc “Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song” considers the life and influence of the Canadian poet and singer/songwriter Leonard Cohen through the prism of “Hallelujah,” his most popular song. Cohen’s “Hallelujah” is, as many readers know, both a spiritual and libidinal cri di coeur, so it’s sometimes compelling and often frustrating to see co-directors Daniel Geller and Dayna Goldfine (“Ballets Russes”) treat the song as an emblem of Cohen’s long career as a musician.

Geller and Goldfine’s docu-collage of interview and concert footage doesn’t give deep consideration to the conditions that led to “Hallelujah” becoming a late career hit for Cohen. This was decades after the song debuted in 1984 on Various Positions, a (rather good) studio album that was rejected by Columbia Records and barely released in the United States. Cohen’s “Halleluljah” is then presented as a trite symbol of his frustrated creative ambitions, though archival interviews with Cohen do effectively suggest that there’s more to his music—and that song, in particular—than the usual artistic triumph over industrial exploitation narrative.

“Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song” glosses over some of the best evidence to support what is, at heart, a basic story: after laboring for years on the lyrics for “Hallelujah,” and then later struggling with his own personal and creative demons, Cohen’s song helped to spark a late-career revival and mini-creative renaissance, too. It’s great to see so much old concert footage from various periods of Cohen’s career. And audio excerpts from Cohen’s interviews with former Rolling Stone reporter Larry “Ratso” Sloman also give viewers some clues as to why Geller and Goldfine only dig so deep into the meaning of “Hallelujah” and its surprising combination of religious and sexual images. But the concert footage doesn’t play long enough to show us what Cohen looked or sounded like when he performed that song, and Sloman’s talking head interviews mostly speak to the movie’s glib understanding of Cohen’s art.

To their credit, Geller and Goldfine encourage viewers to come to their own conclusions, partly as a means of embracing Cohen’s sometimes ambivalent attitude towards explaining his life and music. There are plenty of good and even recent enough profiles and interviews with Cohen, like David Remnick’s impressive 2016 New Yorker profile. And there’s no shortage of concert movies and tribute albums, including the 1974 documentary “Leonard Cohen: Bird on a Wire” and the 1991 cover album I’m Your Fan, the latter of which is credited with helping to revive “Hallelujah” thanks to John Cale’s cover.

Sloman takes credit for suggesting Cale for I’m Your Fan, which is fair, but only so interesting. And while Irish singer/songwriter Glen Hansard has a right to say that Cale is a master of stripping songs down to their essential parts, Cohen’s music was never exactly ornate, with the notable exception of the corrosive and free-wheeling Phil Spector-produced album Death of a Ladies’ Man. That record gets conveniently dismissed as an example of a known producer imposing his will and sound on an elusive artist. As opposed to Cohen’s collaboration with New Positions producer John Lissauer, who now understandably feels vindicated about that album and “Hallelujah” in particular.

Still, Death of a Ladies’ Man is different, just as Cohen’s later albums, especially Popular Problems and Old Ideas, are much more than brief footnotes to the “epilogue” of Cohen’s career. There are several such elisions and omissions in “Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song,” some more telling than others. You don’t need to know that Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ cover of “Tower of Song,” which directly precedes Cale’s “Hallelujah” on I’m Your Fan, speaks to the many ways that talented artists can try and sometimes fail to add to Cohen’s music. There’s also barely any discussion of the song’s “naughty bits,” as “Shrek” co-director Vicky Jenson puts it when she talks about cutting Rufus Wainright’s “Hallelujah” cover from “Shrek” in favor of Cale’s version. But wait, didn’t Cale himself say that he focused on the “cheeky” verses of Cohen’s song? What’s this movie about again, and why are there so many bits of everything scattered throughout?

Geller and Goldfine don’t really go into the specifics of how Cohen’s verses of “Hallelujah” changed over the years (Sloman estimates that there was something like 150 to 180 verses in total). But they do talk with artists like Jeff Buckley, Cale, Eric Church, and Wainwright about their experiences performing “Hallelujah.” All interpretations are valid, according to Church: “none of ‘em are wrong.” Ok, but what’s right about the different versions of the song, and how has it maintained its greatness over time?

A lot of substantial or just different material might have enriched this documentary’s tidy fall-and-rise story. There’s some exciting, but too brief interview footage with former collaborators like Judy Collins, who says of Cohen’s legendary lady-killer rep: “I know dangerous when I saw it.” It’s also great to hear French fashion photographer Dominique Issermann suggest that she didn’t inspire Cohen, but rather was in the right place at the right time when inspiration struck. These are smart and funny observations, but they’re just grace notes in a sprawling 115-minute-long movie that often toggles between the proverbial forest and its constituent trees.

Now playing in select theaters with a nationwide expansion to follow.