“West Ham is mediocre. But their firm is first-rate.” So a young American is told soon after arriving in London. West Ham is a London football team. “Firms” are the names for organized gangs of supporters who plan and provoke fights with the firms of opposing teams. The firms are quasi-military, the level of violence is brutal, and then the gang members return to their everyday lives as office workers, retail clerks, drivers, government servants, husbands and fathers.

I first saw this world in Alan Clarke’s “The Firm” (1988), one of Gary Oldman’s early performances, which showed in disturbing detail how his character was drawn into what the press calls “football hooliganism.” The fights can be crippling or deadly. They’re all the more brutal because the gangs don’t for the most part carry firearms, preferring to beat on each other with fists, bricks, iron bars and whatever else they can pick up. Members of a firm have such fierce loyalty that they disregard risk. Unlike American street gangs, which are motivated by drug profits, British football firms are motivated by an addiction to violence.

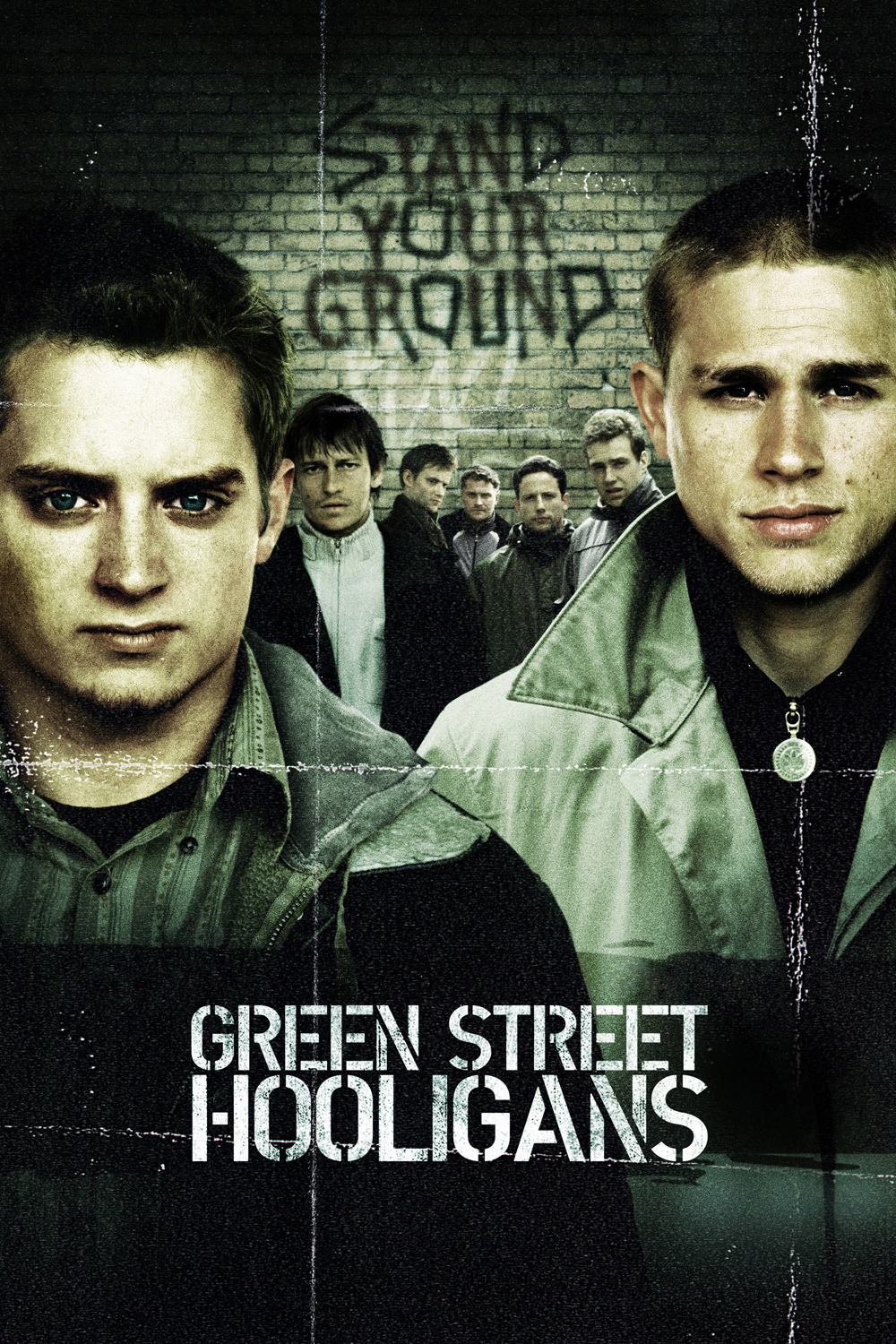

“Green Street Hooligans” chooses an unexpected entry point into this world. Its hero is Matt Buckner (Elijah Wood), a bright Harvard student kicked out of school two months before graduating after his roommate forces him to take the fall for some cocaine found in their room. The Harvard business is not convincing but motivates Matt to visit his sister Shannon (Claire Forlani) in London. Her husband, Steve (Marc Warren), more or less forces his brother Pete (Charlie Hunnam) to take Matt to a football match.

Wood, who can seem harmless enough to be cast as Frodo in “Lord of the Rings,” might appear to be the last person who’d be interested in the violent world of a firm. But the movie is about the way men who run in packs need to belong and to prove themselves. In a series of gradual stages, which are convincing because we see his early resistance wearing down, Matt tries to become accepted by the Green Street Elite. This involves fighting at their side, which he does with more recklessness than skill. When he is finally covered with blood, he belongs.

There’s a lot of plot surrounding this progression. The Green Street Elite lives with memories of its glory days, when it was led by a legendary fighter known as the Major. Its rivalry with Millwall is so vicious that matches between the two teams have not been scheduled since the Major led a particularly nasty fight several years ago. Shannon is horrified that Matt has gotten involved with the Elite, and her husband tries to warn Matt.

But he has become addicted. He was a journalist at Harvard, an editor of the Crimson, and now he keeps a journal: “I’d never lived closer to danger — never felt more confident.” Life in the firm makes his previous life seem insubstantial and unreal; what is real is bonding with other men and beating the crap out of opposing firms.

This seems to me insane. What pleasure can be found in voluntarily seeking injury every weekend? Of course, the fuel of the firm is alcohol, its meeting place is a pub, and its war song is a boozy, defiant version of the last song you would think of: “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles.” There’s an intriguing montage showing Elite members at home and at their daytime jobs; the 1988 Clarke film made clear that firm members are not outcasts, but jobholders and family men who have violence as a hobby.

At first I thought the character of Matt was unnecessary. Why not simply dramatize the world of firms? Do we need a Hollywood star as an entry point for non-British audiences? If you must have one, Elijah Wood seems so very unlikely as a street fighter that I began a list of more plausible actors for the role. Then I realized the movie’s point is that someone like this nerdy Harvard boy might be transformed in a fairly short time into a bloodthirsty gang fighter. The message is that violence is hard-wired into men, if only the connection is made. As someone who has never thrown a punch in my life, I find that alien to my own feelings, but I remember years ago, late on nights of drinking, when anger would come from somewhere and fill me. Certainly alcoholism is essential for firm membership: It is inconceivable that anyone would go into action sober.

The movie was directed by Lexi Alexander, a German woman who is herself a former kick-boxing champion. It uses cinematography by Alexander Buono to capture the everyday reality of London streets and the kinetic energy unleashed in the fights. It also unfolds a tragic back story, as old secrets are revealed, leading up to the ultimate possibility of death. No, don’t assume you know who will die. It isn’t who you might think. Of the dead man, we are told: “His life taught me there’s a time to stand your ground. His death taught me there’s a time to walk away.” I guess the time to walk away is before you get killed standing your ground, unless you have a very good reason for standing it. The most frightening thing about the Green Street Elite is the members think they have such a reason, and it is loyalty to the mob.