“God & Country” is an illustration of that classic conundrum faced by so many political documentaries with an alarmist tone. Even when its concerns are justified, such a project tends to alienate rather than entice, and those who are inclined to agree with its points will come away feeling that their worldview has been reinforced, while the viewers who are arguably most in need of seeing it will remain unaware of it or dismiss it as propaganda. I don’t know what the answer is here, or if there is one—there’s a case to be made that the real purpose of a film like this is to rally the faithful for a battle that lies ahead.

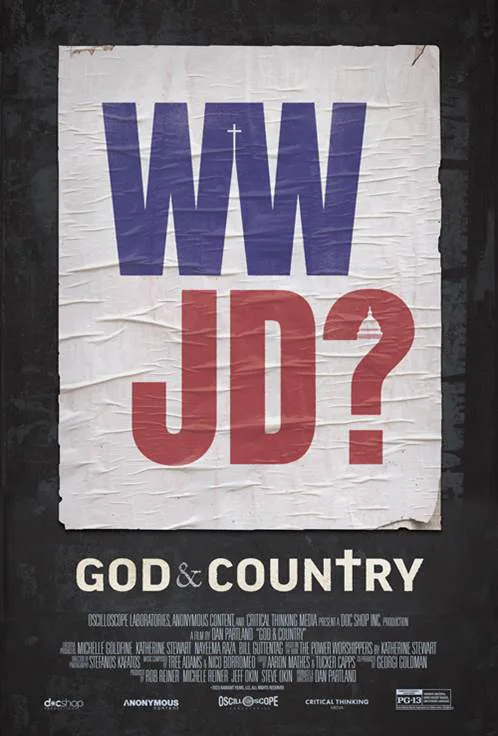

The choice of religious language in that last sentence is intentional. Executive produced by Rob Reiner and directed by Dan Partland (who also did a documentary about former President Trump diagnosing him with narcissistic personality disorder and declaring him mentally unfit for office) “God & Country” investigates the rise of Christian Nationalist beliefs in the United States (spearheaded by evangelical Christians but also folding in other denominations, such as politically conservative Catholics) and the effect on legislation and electoral politics of a national network of churches that are sympathetic to those views and are ideally positioned to get out the vote. The film has an evangelical (with a small “e”) sensibility itself: the end times are at hand, and we cover our eyes and ears at our peril.

As one expert points out, in America a dedicated minority can seize control of the apparatus of local, regional or national government because the citizens are notorious for failing to vote even when the stakes are critical. That’s the threat, and one can see it at work in the banning of books at local and school libraries as a reaction to people who attend school board meetings who not only have zero children in the district but are often from out of state. The film explains that the reactionary wing of the U.S. electorate is louder than it is numerous. It actually comprises about a third of registered voters (far less than the mythical “half” cited by people who complain that such-and-such an entertainer’s liberal political views are alienating to “half the country”). But these are folks who vote, percentage-wise, far more regularly than, say, left-leaning voters under 30, who talk a big game online but don’t turn out on Election Day in numbers significant enough for the establishment to care what they have to say.

Christian Nationalists, the film explains, are working behind the scenes and in broad daylight to restructure the political machinery through gerrymandering, voter suppression, and the installation of friendly federal judges to allow for permanent rule by a minority: theirs. “We are going to impose Christian rule in this country!” declares Rick Wiles, a pastor and the founder of TruNews, a website described as offering “comments on global events and trends with a conservative, orthodox Christian worldview.” Conservative columnist David French of The New York Times accuses this movement of practicing “malice and cruelty and division and partisanship” to further its aims, while Bishop William J. Barber III, a congregationalist minister, criticizes the worship of material wealth and guns, and says that the movement “is so loud about what God says so little about, and so quiet about what God says so much about,” such as ending poverty and “caring for the least of thee.”

The best parts of the film are when it becomes more of a history lesson—for example, in a section counteracting false talking points about the United States always having been “a Christian nation” by pointing out that the government was, in fact, most certainly not based on The Ten Commandments, that George Washington didn’t pray in the snow at Valley Forge, that instituting prayer in schools happened during the 1950s panic over Communism, that the Bible has zero to say about abortion, that “In God We Trust” wasn’t added to currency until 1864, and that the rise of evangelical Christianity as a modern political force happened in the 1980s, largely as a backlash against government-mandated desegregation of schools in the ’60s and ’70s.

In the end, however, the unpleasant truth is that there’s not a lot to see here that you can’t absorb by going down a Wikipedia rabbit hole or watching “The Daily Show” or “Last Week Tonight” or Rachel Maddow. The quotes are chosen for maximum oomph and social media shareability. Among the more incendiary is by Greg Locke, pastor of Global Vision Bible Church, who tells his congregation, “If you vote Democrat, I don’t even want you around this church! You can get out, you demon! You can get out, you baby-butcherin’ election thief!”

The cascade of images intertwines with talking head interviews to produce an effect that’s probably a bit like watching 180 thirty-second Political Action Committee ads strung end-to-end. The soundtrack favors creepy/insinuating “Terrorists have planted bombs, will our heroes be able to find and defuse them in time?” sort of music, although there are a few warm, quieter passages of acoustic guitar and pizzicato strings (but only when the good guys are onscreen). It’s hard to imagine anything in it that might neutralize or overcome the countervailing diet offered by the likes of Fox News Channel, OANN, Alex Jones, or any one of the many local drive-time DJs in large cities who tell listeners that America is being invaded from the south by an army of rapists, terrorists and drug dealers.

The Other Side, as it were, makes films like this, in the opposite direction. The cutting is breathlessly fast. Maybe I’m nostalgic for the sorts of documentaries that would have brought a camera into one of the churches briefly mentioned in this movie and let the parishioners and clergy talk to the viewer and each other and give us a sense of the culture and belief system that produced them, as well as the threat they pose to democracy. Or maybe I just want something more like the dominant American documentary mode of the mid-twentieth century, where the primary purpose was to, well, document, and there were likely to be stray marvelous or mysterious details: splashes of color preventing black-and-white readings.

There are other media, other ways, to do what this movie is doing. I agree with its politics almost completely, but would still rather have watched one of those queasy, politically and morally slippery right-wing action films by somebody like Mel Gibson or S. Craig Zahler again, or a social realist drama by somebody like Spike Lee or Ken Loach, whose values reflect my own, because then I’d see some art.