Writer-director John Sayles has been working on the edge of popular acceptance for several decades now, starting with his counterculture drama “Return of the Secaucus Seven” and continuing through an increasingly ambitious, often sprawling series of ensemble dramas, the best of which is probably “Lone Star.” Although he’s not above the occasional visual flourish, he’s very much a meat-and-potatoes dramatist, more concerned with what people say and do in the moment than in how those words and actions are pictured by the camera. At their worst, his films can seem overly literary, like short stories or novels that just happen to be told with actors. At their best they can have the casually immersive quality of well-made plays or adult, intelligent TV series, with an sharp ear for the rhythms of real speech and an eye for the way people’s body language can give away what they secretly desire.

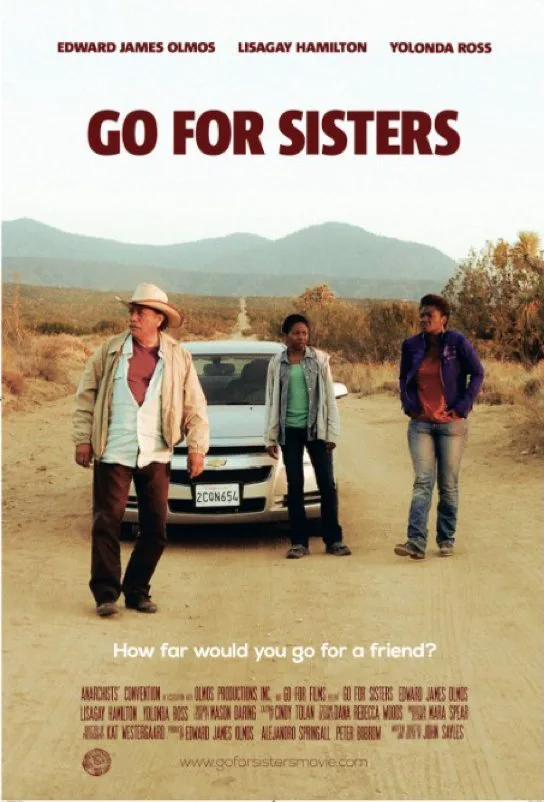

Sayles’ new thriller “Go for Sisters” is stranded somewhere between those two extremes. It’s a story of two childhood friends, a parole officer named Bernice (LisaGay Hamilton) and a recovering drug addict named Fontayne (Yolanda Ross), who team up to solve the mysterious disappearance of Bernice’s troubled son Rodney, a suspect in a killing. The film’s title is explained in a throwaway bit of dialogue early on: as kids, the women were so close and so compatible that other people thought they could “go for sisters,” or be related. Their journey takes them across the border into Mexico, where they navigate a grubby underworld of drug dealing and human trafficking with help from a retired cop named Freddy Suárez (Edward James Olmos), who has an eye disease and is slowly but surely going blind.

As you can imagine, there’s a strong (but mostly subtle) aspect of role reversal here. Bernice, the “respectable” one of the friends, steels herself for a dangerous mission and shows that she has the backbone of a street-tough law enforcement officer, despite having gone straight into an administrative job. Fontayne, who’s lived her whole adult life on society’s seedy fringes, uses that hard-won knowledge for a noble purpose, helping her friend by posing very convincingly as a cop, taking some cues from Freddy but mostly accessing a side of herself she never imagined existed.

Freddy, meanwhile, is acting out his own psychodrama. He’s clearly restless in retirement and frustrated by the limitations imposed by his loss of sight; after saying an amusingly quick goodbye to his wife and assuring her that the mission is really not that dangerous, he plunges into a “case” that has a touch of seventies movie seediness, with shadowy figures misdirecting the heroes at every turn as they try to solve a puzzle that seems deeper and more confusing by the hour. In theory Freddy is “helping” the women, but it’s instantly clear that this is a self-serving justification. He needs to be back in the game because it makes him feel whole.

Sayles is never better than when he’s delving deep into characters working together or at cross purposes, and pointing out how the reasons that people give for doing things are rarely the real reasons. He also gives you a sense that these characters existed long before the film began—that they have tangled personal histories that affect their decisions in the present. There are fine one-off scenes throughout (a wonderful exchange between Olmos and Hector Elizondo, as an old friend who runs a bar, is a standout). He also has a good journalist’s eye for cultural details. The Mexico scenes have a different pace and energy than the suburban US scenes, and only occasionally lapse into south-of-the-border-heart-of-darkness cliche (the worst is a scene involving a Chinese immigrant “snakehead,” or human trafficker, that verges on Charlie Chan-style sinister orientalism).

The film’s plot is articulated cleanly, if a bit too plainly at times, but as is so often the case in Sayles’ movies, that’s not where the director’s interest lies. “Go for Sisters” lacks the epic quilt qualities of such sprawling Sayles pictures as “Lone Star” or “City of Hope,” but this seems more a matter of intent than evidence of any sort of failure of vision.

Sayles’ golden period was the ’80s and ’90s, when a particular sort of American independent film gained unexpected popular traction: one that prized psychology and a sense of place above everything else (“sex, lies and videotape” and “Sling Blade” are just two examples). “Go for Sisters” feels very much like a product of that era. It’s warm, incisive but meandering and a bit lumpy at times. Your affection for it will probably depend on how much patience you have for films in that mode. It’s the sort of film that isn’t afraid of pausing the story to let the characters deliver amusing anecdotes or heartfelt confessions (Bernice tells Fontayne a story about her martial history that’s all the more poignant for being underplayed).

There’s even a scene involving Bernice, Fontayne and Freddy that starts with Freddy rocking out on electric guitar, and telling the women that when his father moved his family from Mexico to the U.S., he decided to get into a rock band because that seemed like a very American thing to do. The camera hangs back without cutting, letting Olmos talk and strum, and part of the delight of the scene is our realization that this scene is probably in there because somebody involved in the production knew that Olmos could really play guitar and thought it would be fun to let him do it.