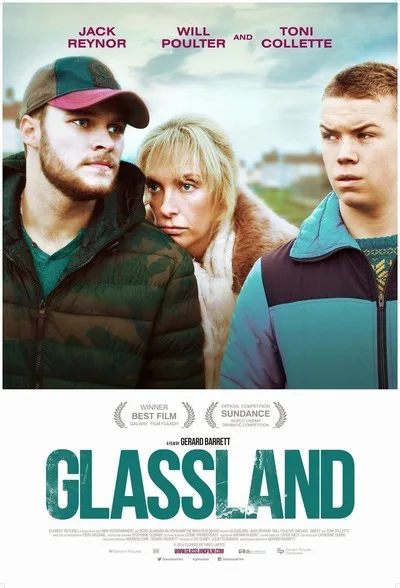

Movies alone don’t have the power to discourage people from drinking or encourage them to stop; but if they did, “Glassland,” about the relationship between an alcoholic mother and her grown son, might not be a bad candidate to show on Intervention Movie Night. Written and directed by Gerard Barrett, this intimate Irish drama travels a road that’ll be familiar to anyone who’s ever seen a film about addiction, or known an addict, but the fact that all stories of addiction are essentially the same doesn’t blunt its impact.

Jack Reynor plays a Dublin taxi driver named John who seems to spend much of his rather paltry downtime coping with his mom , Jean (Toni Collette), who by more than one person’s estimate is drinking herself to death: suicide by debauchery. The film is a record of things experienced and seen, no more and no less. It starts with Jack waking up in the morning, and very quickly it gives us a glimpse of what it’s like for him to share a flat with his mum. The place is a mess, there are dirty dishes piled high in the sink, and he waters down the milk he puts on his cereal, which is either a sign that they’re low on money or that nobody in the house has the time or energy to go to the store.

The first time we meet Jean, she’s passed out, seemingly overdosed; as soon as she recovers, thanks to her son scooping her up and taking her to the emergency room, she starts drinking again. John watches her while trying to get her to see herself. At one point he even takes out his cell phone and records one of her drunken, screaming rants, to give her an objective point-of-view on what it’s like to be around her when she’s at her worst. This has no effect on Jean. She doesn’t need his pity or his attention. She can quit any time she wants. She’s just having fun. It’s no big deal. She’s got it under control. And so on.

And yet there’s nothing condemnatory in John’s gaze, or the movie’s. This overgrown boy still loves his mother, even though she makes his life hell and seems determined to kill herself one glass at a time. Sometimes he stares at her adoringly even when she’s downing glass after glass of wine and dancing around the kitchen to “Tainted Love” (a rather on-the-nose music choice, but acceptable; sometimes life hands you a soundtrack). Sometimes he even drinks with her. Why not? That’s all she ever really does: drink. If you want to relate to your mom you have to find common ground.

Is John an enabler? In some ways, yes. But he also genuinely wants his mom to stop drinking, and it’s questionable whether a colder approach with Jean would yield a better result. Here’s the thing about addicts who are in a relationship with a sober person, be it husband-wife, friend-friend, or parent-child: no matter what the sober person does, it’s always the wrong thing, or not enough. He’s too nice or too mean, too forgiving or too unforgiving, too indifferent or too involved, too this or too that. It’s an impossible predicament. The sober person feels a deep sense of responsibility coupled with frustration over not being able to do anything that will unquestionably, tangibly help. It’s ultimately up to the addict to decide to change. Jean’s not there yet. Jack worries that she’ll never get there, that she’ll just keep drinking and drinking and then she’ll be gone, and he’ll blame himself, even though her life wasn’t his to save, and he did the best he could.

The two lead performances could not be better. Collette makes a powerful impression in a traditionally big, even explosive role; she gets to booze and dance, fall apart, scream, cry, yammer, make an ass of herself, dissolve in self-pity. But none of this quite feels like actor-y showboating because Collette invests Jean’s behavior with a slightly detached quality, as if she’s half-outside of her consciousness, observing herself as she acts out, and up. This is a common characteristic of drunks, who can feel simultaneously uninhibited and painfully self-conscious, socially awkward and theatrically exuberant. Reynor has the subtler role. It’s largely reactive. Because John is an articulate but not always forthcoming person, there are many scenes where we feel absolutely certain that we know what he’s feeling but don’t really know what he’s thinking, or what he’ll do next.

This is a hard, spare, tough movie, at times nearly jarring in its lack of adornment. Barrett is mostly content to pick a camera angle and watch his characters behave. Once he’s made his point, he cuts away, sometimes in the middle of a song, an argument, a rant, or a look. There’s a quietly violent quality to the direction; we keep having moments taken away from us and forced to reorient ourselves and look at something else, something new, even when we’re not ready. The net effect is not one of intoxication, as is the case in films like “Leaving Las Vegas” and “Under the Volcano,” but enforced sobriety. The film is told not through the eyes of a drinker, but somebody who cannot stop a loved one from drinking. Its rhythm and tone have a morning-after feel: the movie is banging on pots and pans and telling you to get out of bed and have some coffee. Now.

.