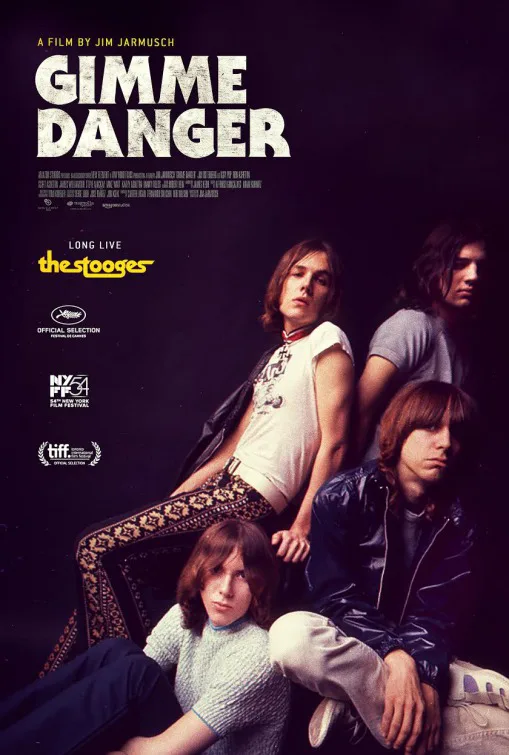

In a sense, the weirdest thing about “Gimme Danger” is how not weird it is. Its subject, James Osterberg, also known as Iggy Pop, also known as Iggy Stooge, is not just a rock and roll survivor (so to speak) of the first stripe. He’s also, like it or not, one of the maverick eccentrics of the form and the lively arts in general. He’s a rock classic, but if your idea of Classic Rock is Boston, he’s also a major weirdo. Similarly, Jim Jarmusch, the director of this documentary, is a filmmaker whose work is arguably not inaccessible but whose aesthetic lies pretty far outside of what we know as the mainstream. “Gimme Danger” is by far the most conventional film he’s ever made. I think that’s a very purposeful feature of the film.

“Gimme Danger” is subtitled “Story of The Stooges” and that’s important—the movie doesn’t give much play to Iggy’s long and varied solo career, which at many points was far more commercially successful than that of the band he co-founded and fronted in the late ‘60s. Jim Jarmusch has described it as a “love letter” to the Stooges, but it is also a kind of brief for the band. Its accessible form, in which the normally more minimalist Jarmusch resorts to a lot of the standard tropes of the contemporary documentary—talking head style (more or less) interviews, far-reaching archival footage, even animated recreations of events described by the participants—seems to me as an attempt to reach the skeptics in the audience, and convince them that Jarmusch may be right when he calls The Stooges “The greatest rock and roll band ever.”

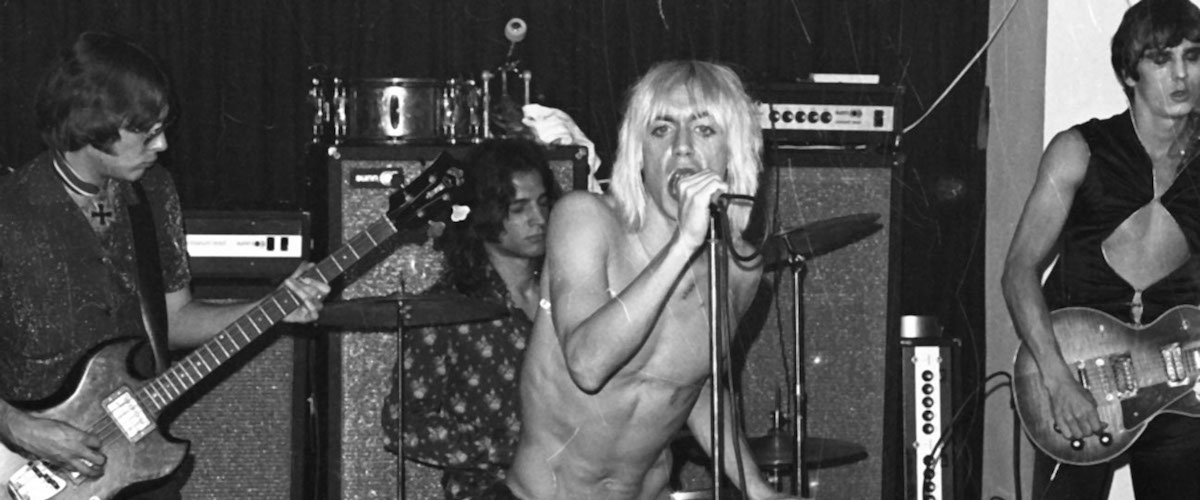

This viewer did not need much convincing, I admit. The 60’s and 70’s Stooges only pulled off one album that I would call “perfect,” which is 1970’s “Fun House,” and the reason I am able to call it perfect is that I have a higher tolerance for horrible noise (which is what that record’s final cut “L.A. Blues” is mostly made of) than many others. Considered without “L.A. Blues,” though, “Fun House” is such a tensile model of ultra-aggressive rock and roll as to be considered miraculous. How did they do it? Iggy has an interesting answer: having assembled the right three partners in musical crime—brother Ron and Scott Asheton on guitar and drums respectively, with Dave Alexander on bass—singer and rhythm technician (trained as a drummer, he collaborated with Scott on the group’s beats) Iggy recalls, “I just started jumping up and down like baboons do when they’re about to fight,” which provoked his bandmates into a sort of frenzy. And the rest is “Now I Wanna Be Your Dog,” and more.

Both Ron Asheton and Scott Asheton have died in recent years, but not before reuniting with Pop for a Stooges revival in the early 21st century. Jarmusch has been working on this project for some time, and so was fortunate enough to log good, informative interviews with the relatively taciturn Ashetons for the movie. They come across as salt-of-the-earth Ann Arbor guys. Ron explains his penchant for wearing Nazi regalia on stage in the early days by talking about his veteran dad’s willy-nilly memorabilia collecting habits. “It wasn’t anything political,” he says, and probably was not, but it was still a crummy idea and Asheton seems to realize it while also believing it might not be very rock and roll to admit it. James Williamson, the “Raw Power” guitarist memorialized in Pop’s solo song “Dum Dum Boys” as the Stooge who’s “gone straight” (and indeed he had a prosperous career in software development at Sony after he got out of music for a while), brings a somewhat more plainly objective perspective to bear when considering the drug-fueled anarchy of some Stooges gigs and tours. Pop himself recalls “upsetting people wherever we went.” In an often-seen clip from the Dinah Shore talk show of the ‘70s, he boasts, “I think I helped wipe out the ’60s.”

And what a way to go. Jarmusch lays out the Stooges story in a coherent, linear fashion. Fans like myself won’t necessarily learn a whole lot that’s new, but it’s salutary the way Pop pays respect to the black musicians he followed from Detroit to Chicago during the musical apprenticeship of his teens. Johnny Ramone rather controversially said that with the Ramones he wanted to create an aggressive rock form that was, among many other things, “white,” and cited The Stooges as a model in this respect. “Gimme Danger” shows that Stooges music, like all rock, had deep roots in black music, albeit a black music that did not get heard much outside of certain regions of the country.

But of course it took the personalities and proclivities of the band members to make their new thing happen. Early champion Danny Fields cites their genius and “their lack of professionalism”—talk about understatement—as being so intertwined as to be inextricable. And yet from the expanding wreckage the Stooges left in their wake there was a good amount of great music and an even bigger amount of influence. The movie is frequently moving, particularly in its account of the alcohol-abetted death of bassist Alexander, and the almost phoenix-like rise of the reunited band in recent years. This is a history lesson that, conventional or not, rocks hard. It can’t help it.